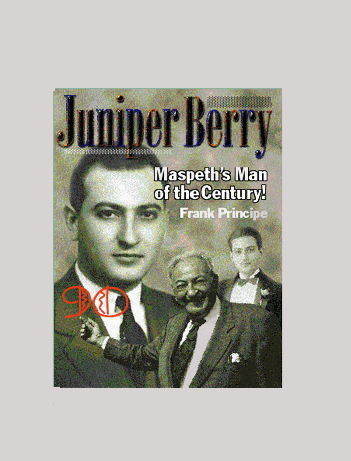

This is the second installment of the life and times of Frank Principe, Mr. Maspeth, the man who for more than 70 years etched his thumbprint in a community. Frank, who now chairs Community Board 5, will be 90 years old on December 5. This is an attempt to chronicle some of Frankís accomplishments over the years, although such a task would require a book length treatise. As we pick up Frankís life again in 1931, shortly after he graduated Cornell University with a civil engineering degree, Maspeth had a bad reputation. That was the place where bodies got dumped, next to the slaughterhouses, next to the cemetery, and next to the incinerator on Betts Avenue where they used to burn dead horses. You could always tell you had arrived in Maspeth, named after the Maspatches Indian tribe that once lived along the shores of Newtown Creek, because you could smell it. But, as you made your way upland, heading East, over a hill that overlooked Manhattan, and you dreamed a little, you could picture a community, a place where a future could be made. Thatís where Frankís future would lie, yet that future was still inextricably linked to his father, Louis, a flamboyant personality who had meant so much to the young Frank and would be his inspiration throughout his life. Here, Frank will come out from under his fatherís shadow and lay down the roots that would keep him a part of Maspeth, of what it would become, forever.

It was 1931 and Frank Principe, a studious and quick-witted young fellow with an easy smile and an obsession for sports, was on the street looking for work. But, even with a degree from Cornell University and the experience of having traveled to Europe, meeting a Pope and a world leader, Frank had no luck. Frank was like many other Americans at the time who couldnít find a job. The world economy was in the midst of the Great Depression and jobs in civil engineering were just too hard to come by.

Fortunately, Frankís grandly mustachioed father Louis, who through years of hard work as a laborer, shrewd planning and an affable personality and connections, became a master builder and was making a name for himself in Brooklyn, the Principe familyís adopted homeland. Louis was spreading out from Brooklyn into neighboring Ridgewood and looking beyond. His son Francesco was away in Ithaca, finishing his education, when Louis began a project on what some real estate genius was to call “the Ridgewood Plateau.” It was an elegant sounding name especially because Ridgewood at the time was known as a classy neighborhood and buyers of new homes, it was thought, would want to view themselves as living in an extension of Ridgewood.

Early on, the land on the plateau was once rolling farmland owned by the Maurice family, whose name would christen a more modern day Maurice Avenue and a park, the naming of which Frank Principe would play a large role. The land later also belonged to the Episcopal diocese, which then sold it to the Brooklyn reality association that Louis Principe belonged to.

It was along 65th Place, the former Hyatt Avenue, in March 1931 that Louis began work on “The Gables,” a six-story complex with 60 apartments. Frank graduated in June and after not being able to find work in his field of study took on a series of jobs including one as superintendent and manager of his fatherís building in charge of renting it and keeping it a profitable concern.

It was also the heyday of radio. Along with President Roosevelt's fireside chats, there were also shows like “The Shadow,” which terrified and delighted millions every night. The talent from that show were looking for a place to live away from the bustle of Manhattan where the show was broadcast. They came to Maspeth, where Frank gladly rented stately rooms to 28 “radio artists.” Frank called it “a bonanza” for him during a difficult period of time in America's history.

He also recalls it being a jolly time when his tenants would enjoy festive parties in the Gablesí community room. The entertainers would stay for two years until another downturn in the economy, around 1933, forced many of the radio programs to be cancelled and the laid-off performers forced to find cheaper places to live, Frank says.

During this time, Frank also rented to famed orchestra leader Glenn Miller, who was just a struggling, better-than-average musician trying to perfect his craft and make a name for himself. Frank recalls having to mediate a dispute between Miller and another tenant who didnít appreciate Millerís late night practice sessions. Frank says the woman wanted him to get Miller to quiet down. But, Frank, was a music lover himself and a young man who was uncomfortable playing the heavy. So, Frank says he went to Miller and told him he was going to make a show of yelling at him, strictly for the benefit of the other tenant.

“I told him that after 10 minutes he could go back to practicing,” Frank says, reclining on his basement sofa and laughing at the memory. “He was great. He said he understood the womanís problem and wanted to be considerate. But he had his work to do too.”

Frank says Miller eventually got a job at some casino and couldnít remain his tenant. “I almost sold him a house, though,” Frank says. “But he couldnít buy it because he was travelling with his band so much.”

With the Gables difficult to rent, the Principes decided on a change in direction, a move away from apartment buildings toward single family homes. Frank says one thing that hurt was that Maspeth was in a two-fare zone. Looking back, he thinks itís ironic that now people are looking for homes in two-fare zones.

So it was that in 1934 the Principes began another project: 10 English-style homes along 62nd Avenue at 53rd Avenue. The newly created Federal Housing Administration was looking to stimulate the economy and encourage home building. The plan was to insure loans to quality builders. It was the first time that the government got directly involved in business, a revolutionary concept at the time. But the Republican bankers, who would actually grant the loans, were against the Democrat Roosevelt's socialist-like scheme and needed some persuading.

Roosevelt, however, would guarantee no loan unless the building project met quality of work standards, but he also wanted to get the program in gear. So, after the Principeís homes were built, the governmentís chief underwriter and engineer pulled up outside the homes in a Cadillac to inspect the workmanship.

“They said it was a fine design in a fine neighborhood and a fine investment,” says Frank. “They had the loan rubber stamped in 30 minutes. And it was all done on the hood of the Cadillac. It was the very first FHA loan approved in the country.”

Frank said the so-called Hilldale Homes, which sold for $4,990, were a great deal, especially compared to today's standards. Frank did the promotion and selling of the homes, and, in a brochure he wrote, boasts of the homes' 12 inch concrete foundations, gas heat (another first for builders at the time), and the “other planned improvements” for the area such as the construction of the Midtown Queens Vehicular Tunnel, making Manhattan 15 minutes away.

At the time, it also made more sense to build homes rather than apartment buildings because no one, it seemed, could afford to pay the rent. But the government was so eager to generate economic activity that it became easier for a builder to construct a home and sell them cheap. Builders like Fred Trump, Donald's father, made a mint, but Frank remembers that no other builder put as much care into their structures as his father's buildings. “We created the market,” Frank said.

Yet despite the good construction, sales were slow. Frank himself moved from the Gables to a home on 53rd Avenue, where he learned, after a torrential downpour, that Maspethís sewer system was woefully inadequate judging by all the water that poured into his basement. Frank would thereafter become an advocate for better sewers, and he later got the city to install them.

Prior to this, when Frank was still a swinging bachelor living in the Gables, going to all the dances in Maspeth's Polish section and dating the college-educated daughter of one of his fatherís rich business acquaintances from Brooklyn, Frank saw a need in the neighborhood for a park. Reminiscing about his sandlot baseball days in Brooklyn, Frank wanted the local children to have the same, and a better, opportunity to play sports.

It was at this time too that Frank began his long career as a civic activist. He became president of the Ridgewood Plateau Taxpayers' Civic Association, and would also umpire various local Little League games in his spare time. Seeing a vast seven-acre tract of land off Borden Avenue and 51st Street where an old, inactive city pumping station was located, Frank had a brainstorm of putting a park there. He went to Robert Moses, the powerful highway and bridge builder and then commissioner of parks, but Moses told him the local homeowners would be assessed to pay the back taxes on the property left by the Urban Water Supply Co., a prospect Frank thought was unacceptable.

As time went by, Frank continued to think about the dilemma of gaining title to the property without having to tax local residents. In 1938, Frank finally convinced Moses that the city needed the property as a backup in case the city ran out of water, which it was slated to do by 1945. But, the city was then completing its second water tunnel and the likelihood that the city was going to run out of water anytime soon was low. But Frank proposed that the cityís Water Department sell bonds and the money would go toward paying off the back taxes. Frank said Moses then agreed to turn the property over for a park, but such a deal needed the approval of the Cityís Board of Estimate, on which sat the mayor and the borough presidents.

Frank, in what would become a habit in the civic wars of the future, rallied local residents, and shuttled them down to City Hall by trolley car, not buses as he does today. “I was as nervous as a cat,” Frank says. The Board of Estimate had been meeting for hours, and was just about to close its session, before approving the bond deal, that a frustrated Frank “went berserk.” The cops should have grabbed me,” Frank says.

Frank says he told Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia that he had all the votes from the other borough presidents lined up. All that was needed was a quick vote. Seeing Frank's fiery Italian temper and Frankís finger wagged in his face, LaGuardia acceded to the demand and the vote was passed. “I had my park,” he said. Frank was not afraid of any repercussions from blowing up at LaGuardia, because by this time he had developed a long and friendly relationship with the “Little Flower.”

Moses then built the park with workers from the Works Project Administration by 1940. Then came the problem of what to name it. Frank says another Maspeth civic leader, Walter Sachacz, who was Polish and president of the Taxpayers and Civic Association of Maspeth, wanted to name the park after a Polish hero. Frank had other ideas. He thought the park should be named after one of Maspeth's first families. In May, 1940, Frank got a letter back from Moses saying Frankís idea for Maurice Park “seems to us to be a good one, and we shall take steps to follow it.”

While Frank was in college, his father Louis was developing political connections in the Republican Party, which was trying to become the party of reform after the Democrats' corrupt Tammany Hall politicians held sway. Louis had a reputation for honesty and a large following among Italians in Brooklyn. He was recruited into LaGuardia's political auspices as someone who could help deliver the Italian vote, someone who was “not a politician and not a mobster.” Frank became his father's chauffeur, accompanying him to various parties, fundraising dinners and visits to Italian undertakers, who became generous campaign contributors. Frank would also assist his father, who had little formal education, writing his correspondence and serving as his general aide de camp.

When LaGuardia won the mayoralty in 1933, Louis Principe was appointed superintendent of Public Buildings, overseeing municipal buildings and public bathhouses, but refusing to take a salary. When the elevators in the Brooklyn Municipal Building got jammed with people, delaying WPA workers from getting to work on time, Louis sent his son, Frank, to fix it. Frank, who also worked without a salary, said the elevators were run by women, who he described as “nice, cranky old farts.” After working out a more orderly schedule of breaks and “romancing each and every one of the women elevator operators,” Frank, at that time, a handsome young man in a crisp business suit, got the elevators working great.

Frank said his father hated bureaucracy and, while in office, devised numerous cost cutting devices to save the city money, including recommending the elimination of his own job, for which The Brooklyn Eagle newspaper labeled him the ìEighth Wonder of the World.î Louis lasted six months in the job before he went back to building homes in 1935. Frank said that early experience of working with his father ìgroomed (him) for the political world.î

Frank said his father died in 1944 at the age of 64 after he contracted a gall bladder infection that was not treated early enough. Louis, who never liked going to doctors, refused the surgery that may have saved his life. Frank, a tear walling in his eye, said his father died of an “error. He didnít have to die so early,” he said.

In 1934, Frank married Frances Camardella and the happy couple moved to one of the Hilldale Homes, the home he still lives in today. Four years later, on July 19, Frances gave birth to Lee James, and then, two years after that, on February 11, to Virginia Elaine. Frank calls his children “the pride of his life.” He involved them, Lee in particular, in his other lifelong love, sailing. Frank said he learned about sailing as a boy, and today, is a commodore at the Cresthaven Yacht Club where he docks his 32-footer, The Virginia, named after his mother.

While selling houses and managing his father's properties, Frank also helped his father-in-law manage some commercial properties, including two movie theaters and a skating rink, in New Jersey, Long Island and Brooklyn. Frank tells how he revived the old skating rink on Empire Boulevard in Brooklyn by installing dance music and importing “girls with short skirts.”

When World War II broke out, Frank said he wanted to enlist so he could belong to a special unit that built bridges, railroad lines and sewers for the Army's occupying forces, a job that was usually done while under enemy fire, and asked for a lieutenant's commission. But, when the Army offered him only a warrant officer job, Frank said he turned the Army down and now believes they did him a favor because that unit had a high mortality rate.

Frank said he then turned to the private sector working as a civil engineer, doing a number of bridge and road jobs on Long Island and in Brooklyn. But, when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and the country was using all available steel for the war effort, those construction jobs dwindled.

Then a friend told him about the government wanting to build an aluminum plant in Maspeth to make munitions for the war. Frank would play an instrumental role in seeing that the plant was built and functioning to make sure the U.S.ís war effort was a success.

But, that is the subject for Part III, which will include Frank's startup of a concrete company and his own fight to keep organized crime from taking over, as well as his more recent efforts on the civic front to make his community better.

End of Part II

Next issue – part III

Frank and World War II