A Block that accomplished a great feat and it’s a testament to what ordinary citizens can do to gain control over their lives.

Living on a dead-end street has its good and bad aspects. If you’re a kid, that means virtually uninterrupted stickball games because no through traffic means fewer cars passing by. Grownups enjoy that aspect too — the reduced traffic, not the stickball games.

I know this to be true because I grew up on 75th Street between Caldwell and Eliot Avenues, which is technically in Elmhurst but residents also claim to live in Middle Village and Maspeth, the borders all coming together about there. The street dead-ends at a small patch of land owned by Conrail and a bridge on Eliot that passes over the Conrail tracks below. I now like telling people I’m a “Dead-end Kid,” which usually gets a chuckle.

My parents, Rosemarie and Frank, were one of the first to buy a home on the block when the attached, red brick, two-family homes were built in 1961, when Juniper Valley Park was still a swamp. My parents still live there, even though my brother and I have moved on, me to Glendale, my brother Gary to Maryland.

When we moved in, there was a small farm on the northern end of the block that had horses, chickens, goats and some land that the farmer, Freddie Breitinger, tilled and worked. Across from the farm on the other side of Caldwell used to be greenhouses where they’d grow flowers and such, which I assume serviced the abundant cemeteries in the borough.

The greenhouses are gone now, as are my school friend Kevin O’Brien’s home and the farm. These all made way for the construction of more brick homes, construction of which is still going on now, filling up every available vacant space in the area. Congestion is now simply incredible, but that’s another story.

Behind the homes on the western side of the street are our backyards and the yards of the people who live on 74th Street. The Conrail freight-train tracks run behind the homes on the other side. We lived on the 74th Street side at 60-36. We could always hear the rumble and rattle of the train every time it passed. And we were thankful we didn’t live on the other side of the street because of the noise. But we also envied those “across the street” because their backyards were bigger than ours.

Those tracks, set in a valley-size depression in a wooded landscape filled with trees and small wildlife, were a constant source of adventure for us kids. But it also raised some fright in our parents who were worried we’d get squashed by a train, bitten by a rat, or suffer a broken leg after a tumble down the steep slope. None of those things ever happened to us as far as I know, although one year a body (nobody we knew and already dead) was found down there. As a kid, my friends and I had fun laying pennies on the rails so they could be crushed into weird shapes by the train or building “forts” in the trees for our youthful wargames.

The bad aspect about living on a dead-end street is that you’re isolated. Getting off the block can present a problem if you want to go to school or to a store. Access and freedom of movement become very important to your quality of life.

When the houses were erected, the builders created a narrow walkway leading to 74th Street halfway down the block. This easement, one house away from my parents, separates the houses on our side of the street.

Our neighbors who lived on either side of the walkway never liked people walking by their windows and the kids playing tag through it, making noise or riding their bikes through it and slamming into the fences. They tried closing it one year when I was little, but my father spearheaded an effort to get a court decision to make them open it.

The walkway is unlit, a little scary, never shoveled in the winter and always leaves an ankle high puddle when it rains. Also, for many people it is inconvenient because you still have to walk halfway up 75th Street, down the walkway, and halfway down 74th Street to get anywhere.

The other way off the block is to head toward Eliot Avenue, scoot between two wooden fences over a step and walk through a gas station that abuts the patch of Conrail property that is always overrun with weeds and illegally dumped garbage.

On our way to Our Lady of Hope Grammar School every morning, my schoolmates and I would take this route. My brother and I would also use this way to pick up groceries for my mother from the stores across from the school. My father went this way to work every morning when he caught the bus to Woodhaven Boulevard on Eliot. Most everybody on the block did the same.

Earlier this year, the gas station changed owners and they closed the passageway fearing a lawsuit if someone tripped walking through their property. It was their right to do so. But they sealed off the block and eliminated something that had been there for 35 years. Many on the block no longer considered the mid-block walkway a viable alternative. The passageway’s closing amounted to a crisis.

So enters my father, who friends call “Buddy.” He was recently retired and itching for a project for himself and his new computer. While always active in the church and in his children’s lives, my old man never warmed to civic matters much. But this problem presented a threat to his way of life and to those around him. He seized the torch, getting a crash course in politics in the process.

Organizing a ragtag assembly of neighbors, my father formed a block association, later incorporated, and its members remained united in the cause of freedom, which meant opening a passageway to Eliot. He started a newsletter, which included updates on developments and later included birthdays, graduation notices and other block gossip. He also launched a fundraising drive, gathering $5,000 in only a few short weeks. Tenants and some local merchants pitched in too.

When it became apparent that the gas station owners would remain adamant, despite appeals (and a veiled threat to boycott the station by the 100 families in the association) from my father, the only alternative was to approach Conrail, despite its generally well-known reputation in civic circles of being one of the most unresponsive entities to deal with. My father, however, new to civic life, didn’t know this and he remained undaunted.

He set about cultivating some contacts. A plan was devised, something kind of revolutionary. A block association, instead of simply whining, would actually build its own walkway across Conrail’s unused and generally forgotten-about property, to link 75th Street to Eliot Avenue and the civilized world. The plan (and the architectural rendering) was greeted positively by my father’s contacts, but being bureaucrats, revolutionary ideas don’t sit well with them. They needed reassurance and asked my father to get approvals from the local “powers that be.”

This proved to be a frustrating endeavor, but my father remained focused. He fired off letter after letter to all our local politicians, schmoozed with their aides, and even met with some of the pols. He contacted Karen Koslowitz, Joseph Crowley, Thomas Ognibene, Serf Maltese and Gov. Pataki. He also contacted Community Board 5 and the Juniper Park Civic Association. Writing his own press releases, he also got reams of publicity in the local press.

When a picture of my parents and a few neighbors appeared in the Daily News, I took it to work to show my friends. I was really proud of them.

Things were going along smoothly until “the snag.” One block resident was equally as determined to see the new walkway plans defeated because partly he didn’t want people walking in front of his house and also because he didn’t like the idea that it might become a hang out for teenagers. This man cultivated his own contacts and bombarded the pols and Conrail with calls. One politician tried to mediate, which almost led to a picket of his house (he lives on 74th Street).

A compromise was reached. The walkway would be built, but it wouldn’t open in front of the man’s house. Conrail was slow to fork over a lease to the new 75th Street Block Association, Inc., which nearly drove my old man crazy. But fork over they did, after the association got insurance and promised to maintain the walkway.

Another fundraising drive was launched. This took the form of block-wide lawn sales and a raffle, which raised another $2,000. A “construction crew” was assembled (all local residents and volunteers), the patch of Conrail land was cleared and leveled, concrete was poured and a fence was erected.

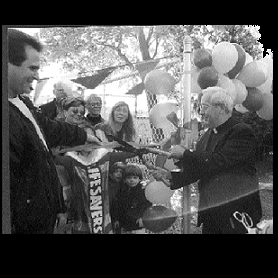

On Halloween, the new 150-foot walkway, wide enough for a wheelchair, was decorated with balloons; flowers and hedges were planted nearby and hot dogs were distributed. Msgr. Sivillo Pastor, the Our Lady of Hope pastor and my father’s friend, running late to an afternoon wedding, hastily blessed the new passageway and cut a pink ribbon to the uproarious cheers of some 50 block residents, some in costume. No politician or Conrail official attended.

My father says the whole 10-month experience brought the residents together. I can see that it did, and I sometimes regret no longer living there anymore, although my wife and I stop over often enough. They accomplished a great feat and it’s a testament to what ordinary citizens can do to gain control over their lives.

While a small chapter of the block’s history closes, a new set of homes where the farm used to be is now up for sale. A new chapter is opening, but I’m sure my father and the rest of his neighbors will be ready for it.

I have to mention a few names of the people who helped or my father will kill me. Here they go: Rosemarie Toomey (my mom; it’s my story), Dennis and Marian White, Joseph Tramontana, Ken and Joyce Quagliata, Dmytro Fedkowskyj, Helen Macellaro, Ed and Ronnie Fernandez, Jerry Crilly, Rose Angelicola, Officer Karl Steinninger, Teddy Matagrano of the Starship Service Station, the Eliot Market, and the Amoco Station. Also thanks to Conrail, the 104th Precinct and the politicians.