Dad, Mom, my sister Judy and I lived in the “little red house” on Crematory Hill. Even though the Great Depression was officially over by 1935, we were still living under its gloom and were desperately poor. My father’s Aunt Margaret, who was President of the crematory, which was next door, came to our rescue by letting us live rent-free and gave Dad a steady job.

At the age of three, I didn’t know such fictional characters as The Frankenstein Monster, Dracula and The Wolf Man. And for that matter, I was yet to hear of real horror such as Jack the Ripper, Lizzie Borden, and an assortment of body snatchers. Still, living on the Hill with a cemetery across the street and the crematory right next door made me sense something threatening. When Mom took us shopping in Jamaica, New York, I noticed the difference. Jamaica was bustling with people and we felt safe among them. In the evening on the Hill, with the crematory closed, the only living people were our family and one neighbor, Mrs. Wagner. Everyone else was dead. The cemetery and the crematory held their dead. We held each other. Nights were lonely and almost always quiet.

Our house was so close to the crematory that one of its gratings was actually laying on our lawn. Voices from the bereaved could be heard coming up from the spaces between the crossed metal bars. Almost every day there were visitors to the crematory’s downstairs floor. Judy and I heard moaning, weeping and wailing, sometimes so loud that we looked at each other and laughed. Occasionally we heard the sounds of rifle shots, bugles blowing and the slow steady beat of drums, most of which came from the cemetery.

Each day on the crematory grounds I saw funeral cars and caskets. Occasionally I visited funeral parlors with my family whenever friends and relatives died. Several times we paid respects to the dead who lay in coffins in my loved ones’ homes. When I was ten years old and living in Ridgewood, New York, a friend my age surprised me when he said, “I find it hard to believe that I’ll ever die.” Another said, “Life will last so long I doubt I’ll ever reach the end.” While very young I saw death as a reality. I knew I’d die.

There was something mystifying about the crematory, especially when I was three years old. Sometimes, when a well-known person was being cremated, it drew a crowd of curiosity seekers. Although I might not have known what was going on, I wondered about all the solemn faces. On one of those days, I was witness to a mass of people whose only reason for being there was the cremation of Bruno Richard Hauptmann. He was the accused kidnapper of Charles Lindbergh’s twenty-month-old son. The little boy was kidnapped seven months before I was born, so by the time of my birth the new law was in effect that every newborn had to be foot printed. (If anyone is interested, a copy of my footprint is in my old jewelry box.)

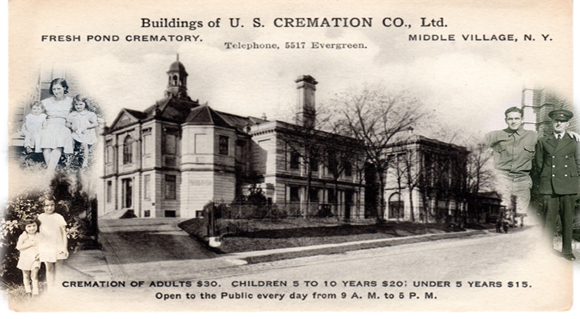

To my young eyes the crematory seemed immense. Viewed from below the Hill it was quite a sight. Facing the crematory, one would see the main building and its entrance on the extreme left. It housed the office and large rooms with wall niches where families of the deceased kept loved ones’ ashes. The building to its right was fully attached to the main one, but by design it gave the impression of being separate. This one contained seven retorts (ovens) used for cremating the deceased. The building to its right was next to our house, the one with the grating from which Judy and I would hear all those mournful cries. Between these two buildings were a passageway for funeral cars and other vehicles. Still, the two buildings were connected by a covered walkway on the second floor. I looked up at it often, but could not see anyone cross through. Because of that and by its strange appearance, it held a great mystery for me.

Every day the crematory closed at 5 P.M. After supper and in the dead of night, Dad would go out to visit a saloon, leaving Mom, Judy and me alone. As he was leaving I’d ask, “Why are you going out?” “I have to see a man about a horse.”

Thinking he was buying one always satisfied me. He did not return while I was awake. On those nights, with the crematory next door and the cemetery across the street, noise came so infrequently that when it arrived its suddenness was unpleasant and unwelcome. A fast moving car was fine. A slow moving one made Mom suspicious. An automobile slowing to a stop just outside our house made her lie down with us making my heart feel as if it were beating in my throat. Some sounds in the night gave me different and opposite feeling, one disturbing, another comforting. I have never forgotten lying in bed and hearing the sound of a passerby running a stick against the cemetery’s metal fence. The clanging noise of the stick slapping against each metal bar would alarm me at first. Then as the person distanced himself, the one note serenade grew more pleasant. Eventually its sound too died on the Hill.

I didn’t believe the reality on the Hill included thieves and cutthroats, but Mom felt it did and at times she seemed terrified. During daytime there were men wandering up and down the Hill. Most of them looked disheveled and were obviously homeless. They often seemed drunk. Occasionally there were men who unintentionally scared me. They walked with a dragging gait that I learned later on was the result of a disease called locomotor ataxia, which had a negative effect on their brains. In any event, we were led to believe that as night approached, terror was beckoning. Still, for me, I have to say that living on the Hill was mostly happy. It was great stomping grounds for a little boy.