ONE day this winter, on a pilgrimage that will be either blessedly cathartic or unbearably painful, a retired telecommunications worker and graphic artist named Dom Caruso will make his first visit to two gravesites at St. John’s Cemetery in Middle Village, Queens.

Echoes of a Killing

Mr. Caruso, a 70-year-old grandfather in fragile health, will begin by bowing his head at the final resting place of his brother Joey, who died in childhood from the ravages of diphtheria. Then he will stop at the partly submerged burial vault of Dr. Casper Pendola, the young physician who attended to the boy in his final, feverish hours.

At the visit, Mr. Caruso will grapple with how these two departed souls, whose paths crossed by chance, ended up linked forever in a saga of anger and murder. The case turned the state against an individual, the medical establishment against the immigrant community, and family against family, while plunging Mr. Caruso into torment for most of his adult life.

Eighty years ago next month — on Feb. 13, 1927 — Joey Caruso, age 6, died in a tenement apartment in the broad swath of New York then known simply as South Brooklyn. That same day, 27-year-old Dr. Pendola, who like Joey was of Sicilian heritage, died in the same apartment.

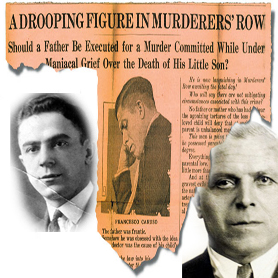

The child succumbed to disease. The doctor was the victim of cold-blooded murder. And the man who killed him, first by strangling him, then by slashing his throat so severely that his head was nearly severed from his body, was Francesco Caruso, Joey’s father.

Sensational by any standards, the slaying set off a maelstrom of news media frenzy, ethnic hatred, ethical and legal debate, and volatile emotion that would keep New York and much of the rest of the nation in thrall for months. The case became a cause célèbre, a campaign for justice for Italian immigrants that drew in Fiorello La Guardia, Clarence Darrow and other boldface names of the day. But however broad the issue became, at its core were a child’s death and a father’s grief and rage.

A Laugh, or a Twitch?

According to court testimony and other documents, this is how events of that terrible night unfolded.

Francesco Caruso, a beefy, 35-year-old Sicilian immigrant and laborer known as Cheech, lived at 36 Third Street, near Smith Street, with his wife and six children. On Feb. 11, his son Joey developed a bad sore throat. The father tried to treat him with over-the-counter remedies. But the next night, the boy took a turn for the worse. With no phone in the apartment, the father ran to a local drugstore, owned by one Joseph Pendola, and the pharmacist telephoned his brother, a physician who lived in Maspeth, Queens.

Arriving around 10:45 that night, Dr. Pendola examined Joey, who lay feverish on a cot in the kitchen, and diagnosed his condition as diphtheria, a bacterial disease that ravages the upper respiratory system.

The doctor wrote prescriptions for 10,000 units of antitoxin, to be injected, and a second medication, to be given orally. The father filled both prescriptions at the Pendola pharmacy, then returned to the apartment, where Dr. Pendola injected the antitoxin. Leaving the father to administer the oral medication, the doctor departed, promising to return the next morning.

During the night, however, Joey grew sicker and eventually became delirious. According to testimony his father gave in court, at one point the boy stood up in bed and announced, “Papa, I am dying.”

By 10 the next morning, the doctor had not returned. Mr. Caruso raced back to the pharmacy and called for an ambulance. He returned home to find that his son had gone into convulsions. The boy died in his arms.

Not until noon did Dr. Pendola reappear at the apartment. It was the events that followed that led to the bloodletting.

According to Mr. Caruso’s testimony in court, upon being informed of the child’s death, the doctor simply laughed, although the New York Court of Appeals would later characterize the doctor’s reaction as “some twitching of the facial muscles that might be mistaken for a smile.”

Whatever actually occurred, the enraged father wrapped his powerful hands around Dr. Pendola’s throat and began strangling him. When the doctor fell, Mr. Caruso pulled a butcher knife from a closet and stabbed him twice, fatally, in the throat. By nightfall, Mr. Caruso was in police custody, charged with first-degree murder.

Newspaper articles describing the crime were predictably sensational. “Physician Is Slain by Crazed Father as Boy Patient Dies,” blared the headline in The New York Times. “Crazed Father Flees Bier; Confesses After Capture,” shouted The Daily News.

Taking note of Mr. Caruso’s Sicilian heritage and lack of formal education, the articles variously described the defendant as “dull-eyed and expressionless,” an “ignorant father” given to speaking “broken English,” and “a raging giant whose black eyes were afire with hate and revenge.”

Deliberations, and Death Row

The trial, before Judge Alonzo McLaughlin in Kings County Court, then at Joralemon Street and Boerum Place in Downtown Brooklyn, had moments of high drama.

Jury selection, which began April 4, proved to be a complicated affair and took two days. When a brief postponement was granted, the doctor’s distraught widow, Helen, stood up in the gallery and shouted: “This man murdered my husband, and it was a cruel, cold murder! He should be killed. Instead, he gets an adjournment.”

Once the testimony got under way, the defendant’s own words were chilling. “I said he had killed my boy and I was going to kill him,” Mr. Caruso said of the doctor. “Soon he didn’t breathe anymore, and I ran to the kitchen, got a carving knife and stabbed him in the throat. My wife stood in the doorway and saw it all.”

Ultimately, the jury rejected the defense’s argument that Mr. Caruso was suffering from temporary insanity and concluded that his actions had been deliberate and premeditated. On April 7, Mr. Caruso was convicted of first-degree murder, which carried an automatic death sentence. As the judge congratulated the Caruso jurors, noting that “any other finding would have been a miscarriage of justice,” the defendant was packed off to death row at the Sing Sing Correctional Facility in Ossining.

Star-Studded Counsel

Then the tide turned.

A campaign to spare Mr. Caruso’s life picked up momentum among Italian-American friendship societies. An ambitious New York congressman named Fiorello La Guardia visited the Caruso family. A defense committee was organized by a press agent named Alexander Marky, and thanks to him, Mr. Caruso’s wife and daughter were able to make appeals for mercy over the radio.

The defense committee recruited renowned lawyers to its cause, including Walter Pollak, who would later help defend the young African-Americans sentenced to death in the notorious Scottsboro Boys case. The committee’s most prominent member was Clarence Darrow, the legendary defender of evolution in the Scopes “monkey trial,” who came out of retirement to help draft Mr. Caruso’s appeal.

On Nov. 22, alleging 14 trial errors and citing more than 100 other cases, this star-studded legal team persuaded the Court of Appeals to void Mr. Caruso’s conviction for first-degree murder and order a new trial. The court’s chief judge was Benjamin Cardozo, who would go on to join the United States Supreme Court.

At the Caruso home, the defendant’s family celebrated the good news with a fat Thanksgiving turkey. At the Pendola home, the doctor’s widow rocked her baby daughter, Catherine, and wept. “We have nothing to be thankful for,” she told reporters. “My baby and I are alone. And the man who killed my husband, my baby’s father, is alive and may go free.”

Mr. Caruso’s new trial began two months later, and this time around, matters took some curious turns. A jury was impaneled in a brisk two hours; the very next day, Jan. 31, 1928, Judge McLaughlin, who had presided at the first trial and sentenced Mr. Caruso to death a scant nine months earlier, halted the proceedings to allow Mr. Caruso to plead guilty to first-degree manslaughter.

The prosecutor, on record as saying Mr. Caruso should face the first-degree murder charge again in the second trial, also did a turnabout, agreeing to the manslaughter plea. The judge then sentenced the defendant to serve a maximum of 20 years.

In the end, Mr. Caruso served only six years. Returning to his family, he fathered another son, Dom, and lived the rest of his life in relative obscurity, working as a laborer, a house painter and a caretaker. He died in 1968, at age 77.

After the Anguish

For decades, Dom Caruso had a troubled relationship with his father, who, in the son’s eyes, despised him because he could never replace his beloved brother. As Dom remembered it, his mother once told him that his father had tried to have the midwife write the name “Joey” on his birth certificate when he was born, but the mother had vehemently rejected the idea.

One morning in 1952, when Dom was 16, his father sat him down at the breakfast table of their Jericho, Long Island, home and, already drunk on red wine, as was his custom, began to tell an extraordinary story.

According to Dom, his father said that Dr. Pendola was not the first man he had murdered. The father, a strapping man of 230 pounds, said that he was a longtime “made man” in the Sicilian Mafia, and that, through beatings, knifings and shootings, he had served as an enforcer for Salvatore D’Aquila, an Al Capone associate and the capo di tutti capi of the New York Mafia.

So, Dom Caruso recounted, when Cheech Caruso found himself facing the electric chair, he was not abandoned. Al Capone and Salvatore D’Aquila helped to set up a defense fund, hire top-flight lawyers to work on Mr. Caruso’s appeal, and orchestrate the abrupt denouement of the second murder trial by pressuring Gov. Alfred E. Smith or one of his top lieutenants. The governor, who would run for president that year, enjoyed huge support from Italian-Americans.

The father’s tale is almost impossible to substantiate. On the one hand, Dom Caruso has no physical evidence of the father’s statements about the Mafia and the trial. Moreover, Dom’s own family has been at least partly skeptical of the tale; for example, his siblings hotly disputed Dom’s claim, based on his talk with his father, that their brother Sal had been named after Salvatore D’Aquila.

As for the involvement of Smith’s administration, the best evidence is very unspecific. Thomas Reppetto, author of “American Mafia: A History of Its Rise to Power,” said that the governor was undeniably under the sway of powerful party bosses, particularly those in Tammany Hall, who would not have hesitated to seek a favor from the Mafia. But, Mr. Reppetto also said, he knew of no proof that Al Smith had ever done favors for the Mafia.

On the other hand, there are some facts that lend weight to the father’s story. On the day after Mr. Caruso’s arraignment, for instance, The New York Times noted that in 1918 Francesco Caruso had been arrested by the police and fined $100 for carrying a concealed pistol, not a fix encountered by a regular laborer. Then there are the turnabouts of the judge and prosecutor at the second trial, and the question of how the costly appeals effort on Mr. Caruso’s behalf was financed, even if it was a cause célèbre.

Whatever the truth may be, it is difficult to know exactly what relatives of the victim may have felt about this claim or about the case in general. Attempts to reach direct descendants of Dr. Pendola — through death, Social Security and newspaper records and through St. John’s Cemetery — were unsuccessful. Among relatives who could be located and did agree to speak was Michael Criss, whose great-grandfather Pietro Pendola was Dr. Pendola’s cousin. Mr. Criss, who teaches at Oklahoma State University and is the unofficial historian of the Pendola family in the United States, said he had first heard about the murder from cousins who were small children when it occurred.

“I think what Caruso did was heinous,” Mr. Criss said, “even if you take into consideration his emotional state. However, I see no reason to blame his family and descendants for his actions.”

•

When one of those descendants, Dom Caruso, visits St. John’s Cemetery, the first member of his family ever to do so, he will find two graves about a 10-minute walk from each other. They are remarkable for their unremarkableness.

Joey’s final resting place is an unmarked charity grave, which was paid for by the Roman Catholic Church’s Society of St. Vincent de Paul.

Dr. Pendola is buried in a marble family vault shaded by pine trees. There is the surname Pendola, but there is no visible monument bearing birth or death dates, and no first name. There are no words of solace or affection, no religious symbols or biblical inscriptions, no mention of the fact that the deceased was a husband, a father and a practitioner of the healing arts.

For Dom Caruso, whose profound sadness over what happened that wintry night in 1927 extends to the Pendola family as well as his own, the primary concern remains how the outcome of the case must have affected the doctor’s widow and daughter, even though he was never able to ascertain their fate.

“I doubt that poor Helen found any peace in her lifetime,” Mr. Caruso said of the doctor’s widow, who, according to Mr. Criss, died three decades ago. “I hope and pray that Catherine did. I’d like to believe that.”

Neal Hirschfeld is the author, with Kathy Burke, of “Detective: The Inspirational Story of the Trailblazing Woman Cop Who Wouldn’t Quit.”

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/07/nyregion/thecity/07caru.html?pagewanted=all