Designing and building Trinity Church was the turning point in Richard Upjohn's life, and his design for St. Saviour's, Maspeth came shortly afterwards. At first it may seem puzzling that he would turn from that elaborate Gothic monument standing at the head of Wall Street—”the pride of Episcopalians and the glory of our city” as Philip Hone wrote in his diaries—to a small, plain, wooden parish church in Maspeth, which was still a hamlet among Long Island farms in 1847. The story of Upjohn's life shows that there was a very personal reason.

Richard Upjohn was born in England in 1802. His father, a surveyor and estate agent, had thought Richard would become a priest, but instead the young man apprenticed to a carpenter in Shaftesbury for five years, and opened his own business as a cabinet maker. Married, with a young son, he experienced a financial failure, and emigrated to New York, leaving a heavy debt. Struggling to make a living, he did all kinds of woodwork and building, first in Manlius, New York, and then in New Bedford, Massachusetts. Despite his precarious position, he was fascinated by architecture, and bought the latest architectural books, including studies in the Gothic revival that was emerging in England. Upjohn’s account books show the purchase of “Gothic Architecture in Parochial Churches” and “Britton’s Christian Architecture”; this, at a time when he wrote to a client asking to be paid in bushels of potatoes, if there was no money available.

In America in the 1830s there was no licensing or formal training to become an architect. Upjohn decided (rightly) that he was an architect, and advertised himself as such. Moving to Boston, he obtained work at Trinity Church, and made friends with the rector, Jonathan Mayhew Wainwright, who subsequently became a powerful cleric in New York. It was through this contact that he was called in 1839 to repair New York’s second Trinity Church, finished in 1790, which had become structurally unsound. Upjohn, a consummate rainmaker, persuade the vestry that a new church should be built, and was hired to design it and oversee its construction.

Here was his opportunity to express not only his artistic leanings but his religious convictions as well. A biography of Upjohn by his descendant, Everard Michel Upjohn, which incorporates family traditions, is titled Richard Upjohn, Architect and Churchman. “Churchman” is a key point of departure. Upjohn was a man of intense religious convictions, and he lived at a time when the Gothic was seen a something more than just another historical style.

In England, and especially at the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, the architectural Gothic revival had become identified with another revival, the return to earlier forms of worship in the Anglican church. Antiquarians looked back towards plainsong and the pointed arch, studying the pre-Reformation Gothic parish churches that they went on to restore and imitate. The Oxford movement and the Camden Society looked for certain architectural features that would embody ancient rituals. Among such features would be a deep chancel, often housing a choir, where the celebrant and the altar would be somewhat removed from the congregation; aisles for a ceremonial approach to the altar through a long, narrow nave; an interior with “dim religious light” and intense colours meant to transport the mind, through a more mystic approach to worship than had been current in 18th century England. To these practitioners, who dubbed themselves “ecclesiologists,” Gothic architecture was “sacramental”, that is, a visible manifestation of an inner truth: it was the only true architectural expression of the Christian faith, the architectural counterpart of the forms of worship they believed in. The work of building or preserving a Gothic church was work in the service of God.

This was in direct contradiction to the deeply held beliefs of protestant evangelicals, who also had their preferred architectural forms, keyed to the primacy of the sermon. Their church was to be wide and luminous, with a shallow apse and a prominent pulpit making for excellent sight lines and acoustics, and the decoration, classical. A New York instance is the Congregational Plymouth Church where thousands listened (and thousands more were turned away) on Sundays when Henry Ward Beecher preached against slavery. Members of the congregation, led by the abolitionist Henry Chandler Bowen, had moved from the Church of the Pilgrims, designed by Upjohn, to a new location, and in 1849 began to build the white, sunlit auditorium where Beecher so successfully held forth.

In 1908 in Architectural Record, Montgomery Schuyler looked back as a critic on the Gothic revival. Schuyler, who found all this doctrinal crossfire amusing, perhaps because he came from an old Dutch family in Albany, wrote in his discussion of St. George’s, Stuyvesant Square by Leopold Eidlitz

But about church-building. The impulse to the Gothic revival in this county came from the Protestant Episcopal Church, and was necessarily “Anglican.” The Anglican tradition meant little to a German [like Eidlitz] for whom its associations did not exist, nor much, comparatively, to a logician, who naturally and necessarily rated its historical examples below those of France…Accordingly the early churches of Eidlitz became, and I find remain, rather rocks of offense to the Anglicans. The very success of St. George’s designated its author as the architect of the Evangelicals rather than of the Ecclesiasticals.

The Oxford movement was compelling to many of the Episcopal clergy, in New York but also in New Jersey, whose Bishop Doane, a patron of Upjohn and an honorary member of the Camden Society, is known to have traveled to preach at the consecration of a Gothic revival church in Leeds, and also visited Newman and Pusey. With such an itinerary he must have seen some of the smaller English parish churches that had become central to the revival. These were put forward as architectural models for new country churches both in England and in America, and Upjohn created one for Bishop Doane: St. Mary’s, in Burlington, New Jersey.

Upjohn believed that as an architect and a man of faith it was his duty to provide Gothic designs for small parishes, and to provide them at a cost the parishes could afford. This was at a time when, despite his fame, he was still struggling to pay off his English debts and educate his large family. His reputation, his connection with Trinity, and perhaps his High Church leanings brought him numerous requests for help from small parishes. In the same year that he prepared the designs for St. Saviour's, Maspeth, Upjohn advertised a publication to be sold by subscription, Designs for Country Churches. (A copy of the prospectus, described by Phoebe Stanton in The Gothic Revival and American Church Architecture, is preserved in an archive at Duke University.) For whatever reason, this project seems not to have come to fruition, but five years later, he published Upjohn's Rural Architecture, a pattern book with extensive plans and specifications for a wooden Gothic church, chapel and rectory, intended for the use of pioneers and new parishes. He moved the High Church Anglican model into the American idiom, using his extraordinary skills to translate a medieval architecture of stone into wooden buildings suitable for the American frontier, adapted to new needs and available materials, without losing the qualities essential to the ecclesiological movement. Phoebe Stanton writes that Upjohn described his proposal as “in all essential features, a church—plain, indeed, but becoming in its plainness.” She continues.

He seems to have been willing to supply parishes that could not afford the complete services of an architect with designs at little or no cost. Credit for this and other sensitive, intelligent and charactistically American transformations of a stone pattern to wood belong to Upjohn.

These church designs from Upjohn’s Rural Architecture have board and batten vertical siding and lancet windows, both single and grouped, a deep chancel expressed on the exterior, and the center aisle and choir stalls appropriate to the Anglican liturgy. Churches built from this pattern book exist in far flung locations, and some are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Perhaps Upjohn’s early experience in architectural woodwork came full circle when he designed these small, spare wooden structures, the chapels adapted to gather together even the least of congregations.

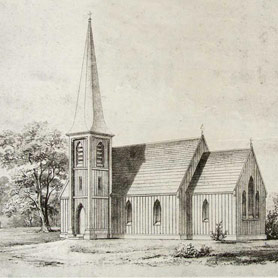

Whether St. Saviour’s was in any way a prototype for the church illustrated in the pattern book is debatable; there are differences and similarities. The pattern-book church is a little smaller, and has a steeple, while St. Saviour's has a plain bell tower, like so many parish churches in Upjohn’s home county of Dorset. But both have the board and batten exterior, the lancet windows; the chancel and its east window are the same, and Rural Architecture could be mined for information in a restoration of St. Saviour’s.

It is possible that St. Saviour’s also looks back to St. Andrew’s, East Lulworth, Dorset, which has an almost identical massing, and even the fieldstone retaining wall that sets St. Saviour’s apart. English parish churches are most often framed by a generous church yard which includes old trees and a cemetery, just as at St. Saviour’s. Upjohn wrote:

The object is not to surprise with novelties in church architecture, but to make what is to be made truly ecclesiastical—a temple of solemnities—such as will fix the attention of persons and make them respond in heart and spirit to the opening service—“The Lord is in his Holy Temple.”

At the time St. Saviour's was built, the nearest Episcopal church would have been St. James, Newtown which was an inconvenient distance away; this church, built in 1735, is still standing, though without its tower. It was covered in asphalt shingles in the 1960s, just as St. Saviour's has been, but in 2001 received a state grant for restoration.

It is sad indeed that a church with so much history, and one that tells so much about the work and character of a major American architect, is now threatened with demolition. St. Saviour’s has been the centerpiece of its neighborhood for more than 150 years; it still has passionate defenders, because of its history, its picturesque character, and the open green space of the former churchyard with its cemetery and old trees—a public benefit over the years. It stands on Maspeth Hill, two acres that could be parkland, with a commanding view toward Manhattan; land originally given by Congressman James Maurice and vestryman John Van Cott, who believed, according to the deed of donation, that their beautiful gift would be forever separated from “all unhallowed, worldly and common uses.”