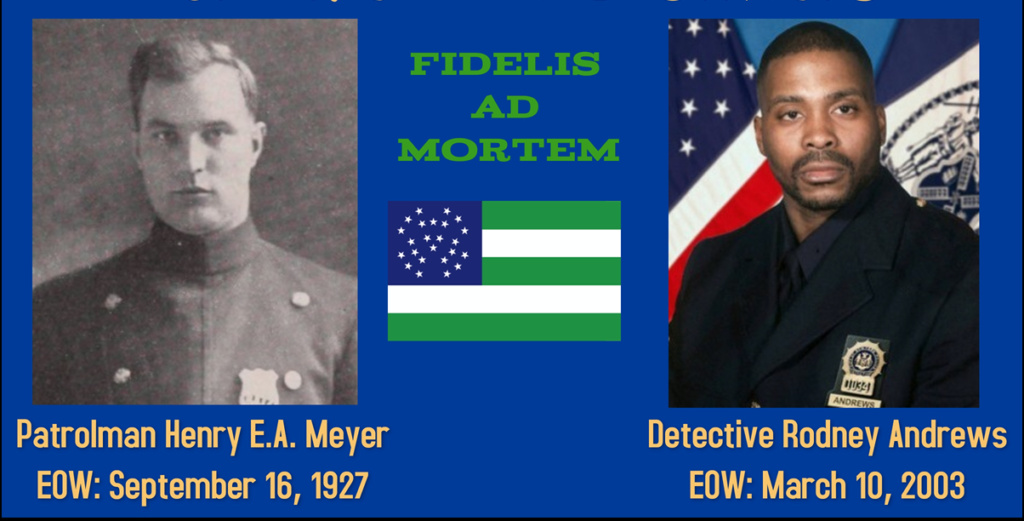

Last year, the stories of two NYPD officers who died in the line of duty and lay at rest at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Maspeth were recounted. This year, we’d like to tell you about two more who are buried locally. One was a well-respected member of the 104th Precinct who was killed in an off duty shooting and the other was executed while working undercover as a detective. Both have final resting places at All Faiths Cemetery.

Patrolman Henry E.A. Meyer (1886-1927)

The sunny late summer afternoon of Friday, September 16, 1927, Patrolman Henry Meyer of the 54th Precinct (now the 104th Precinct), a 13-year veteran of the NYPD, was off-duty and driving his wife Tillie in their Model T Ford sedan to Atlantic Avenue to do some shopping in anticipation of their daughter’s (his stepdaughter’s) upcoming wedding. They had just picked up his pay at the precinct and were cruising along Cypress Hills Street through the cemetery belt.

Suddenly, Ernest Gesell, a plumber known to Meyer, pulled up alongside the car and told him he had heard the screaming of a woman coming from Beth-El Cemetery and had located two robbery victims. Patrolman Meyer got out of the car and followed Gesell over to the Manhattan women, Mrs. Hannah Lewis and Mrs. Florence Novitt, who had been held up at gunpoint by two men while visiting the mausoleum of their father. After their money and jewelry were stolen, the crooks had locked them in a crypt from which Gesell had liberated them. The value of the items stolen was estimated at about $2100.

Henry returned to his car. He and Tillie proceeded a short distance down Cypress Hills Street looking for a police callbox, but when he started to make a turn onto Cypress Avenue, he spotted two suspicious men walking along the road repeatedly looking back over their shoulders. Henry exited the car, unholstered his revolver, and ordered the two suspects to stop. He questioned them but they denied any involvement. He then asked them if they would consent to allowing the victims to get a look at them. They agreed. Henry did a cursory pat down and instructed Tillie to walk back to the grave where he had left Gesell and the two women, where he would meet her. He loaded the two men into the back seat of the car and drove back to the original location.

Tillie walked back up the hill and as she got to the top she looked back at the road and saw the two suspects fleeing on foot. She dashed over to the car and found a small crowd around her husband, who was lying in the road with a piece of torn shirt cloth in his hand. He had been shot multiple times. Witnesses moved Meyer to nearby Gerke’s Hotel as they called for an ambulance.

Officers from the 54th Precinct arrived and started a search for the suspects. One of them was located hiding in bushes at Gerke’s Ridgewood Park Picnic Grounds, which surrounded the hotel. Identified as 18-year-old Benjamin Rader, he was brought to the hotel to see if Meyer could finger him as the gunman. Unfortunately, Meyer was in too grave a condition to do so. Cops brought Rader back to the spot where he was found, and he pointed out to them where he had buried his share of the stolen jewelry. Then they brought him over to the victims, who positively identified him as one of the men who robbed them and identified the gun from the crime scene as the one Rader had brandished during the hold up. Tillie and Gesell confirmed that he had been one of the men in the car. The torn piece of cloth from Meyer’s hand also perfectly fit a gaping hole in Rader’s shirt.

Two and a half hours after he was shot, Henry Meyer died at Wyckoff Heights Hospital at the age of 41. Henry’s brother, Philip, also a police officer, identified the body twice, first at Wyckoff and then a second time at the Brooklyn office of the coroner, where it was determined that Henry had been shot once in the neck, once in the chest, and twice in the back. He had been shot not only from the back seat of the car, but in a struggle as the perps fled.

“Greasy” Ben Rader, as the press came to call him, was brought to the Glendale precinct, where he confessed that the gun found next to Meyer’s body was his but denied being the triggerman. He described his companion as a freckle-faced red-head and referred to him as “Connors” but didn’t know where he lived. Detectives down at Police Headquarters in Manhattan thought Connors sounded familiar to them. They fanned out to pawn shops and found a shop owner who had been robbed a month earlier by someone fitting Connors’ description. Police confirmed who they were looking for – a 21-year-old named Edward Reilly – and he was tracked down to a boarding house where he was shacking up with the wife of a jailbird. Reilly confessed to the robbery and revealed the location of the pawn shop where he had unloaded his share of the loot. The owner, initially hesitant due to a past criminal history of knowingly being involved in shady transactions, eventually identified Reilly as the one who sold him the rings.

On September 20, Meyer’s casket left his Loubet Street home. Thousands lined the streets as the funeral procession made its way down Metropolitan Avenue to his final resting place at Lutheran Cemetery, where he was buried with full honors. Tillie needed to be supported by officers from the precinct in her grief.

The two crooks together were dubbed by the press as “The Ghost Gunmen.” The bullets from Meyer’s body were traced to Rader’s gun. Just 3 weeks after the murder, the two men were on trial, with Rader’s mother and 16-year-old wife in attendance and sobbing uncontrollably, making sympathetic spectacles of themselves for the press. With a parade of witnesses fingering the two accused, they didn’t have a chance of acquittal but were hoping to escape the electric chair. They successfully argued that the murder was not premeditated as they only were looking to simply rob the women, with Meyer having thrown a monkey wrench into their plans. Both men were swiftly convicted of second-degree murder and illegal weapons possession and sent to Sing Sing for sentences which included hard labor. The judge, unsatisfied that he could not impose a harsher penalty, ordered that the two men also stand trial for robbery, which they were later convicted of, assuring that neither would ever leave prison alive.

Detective Rodney Andrews (1968-2003)

Detective Rodney Andrews, 34, and Detective James Nemorin, 36, were shot and killed while involved in an undercover buy and bust operation In Staten Island on March 10, 2003. The partners had been the first NYPD line of duty deaths since 9/11/01.

One of the detectives had arranged to buy a Tech-9 submachine gun from a suspect who had sold him a .357 Magnum a few days earlier. When Detectives Nemorin and Andrews pulled up to a location in Staten Island with cash ready for their second gun buy in a week, their target telephoned them in the detectives’ car to say he was unhappy that two men had arrived for the gun deal, instead of the expected one. One of the detectives, who had been part of the first gun sale, managed a momentary bluff by saying he had brought along his brother-in-law to make himself feel more comfortable.

The target then instructed the detectives to drive his two associates to another location where the sale would take place. The suspect never intended to sell the detectives a gun, but instead had planned to rob them of the $1,200 they had brought for the deal. During the ride, the detectives signaled through a hidden audio hook-up to their back up that one of the four surveillance cars following them had been spotted and to back off. At one point, the suspects had the detectives pull over at a location so they could “pick up” the Tech-9. When one of the suspects exited the detectives’ vehicle, trailing surveillance cars were forced to drive past to avoid detection. When the detectives’ car began moving again, the surveillance cars lost sight of the detectives, but they could hear over the audio hook-up that the suspects were demanding to search the detectives.

When the detectives questioned the suspects for the reason for the search, an argument began, and the suspects ordered the detectives to pull over. One of the suspects, Ronell Wilson, drew a .44-caliber handgun and shot Detective Andrews, who was sitting in the passenger seat, once in the head killing him. The suspect then shot Detective Nemorin, who was driving, once in the head, also killing him. The suspects then got out of the car and began to walk away, but returned and pulled the two detectives out of the car. One suspect took Detective Nemorin’s gun, and the two suspects then stole the detectives’ car and headed to the apartment of the target suspect. Minutes later, officers in one of the surveillance vehicles located the detectives lying in the middle of the street at the intersection of Hannah Street and Saint Paul’s Avenue.

When the suspects got out of the stolen car in front of the target suspects home, two patrol officers spotted them. The officers were able to apprehend one suspect, but Wilson, who fired the shots, escaped. He ran to the target suspect’s apartment where he left his bloody clothes and Detective Nemorin’s gun. He then fled to Brooklyn, where he was apprehended two days later, along with another suspect who had helped plan the robbery/murder. Within 72 hours, a total of five suspects were apprehended.

In December 2006 Ronell Wilson was found guilty in federal court of both murders and sentenced to death. In June 2010 the death penalty was overturned by the United States Court of Appeals and the case was sent back to district court for a new penalty phase to decide if the defendant should receive the death penalty or life in prison. He then hatched a plot with a female jail guard to impregnate her in a misguided attempt to prevent the death sentence from being carried out. She had his baby in 2013 and was sentenced to year in federal prison for her role in the scheme. In July 2013 Wilson was again sentenced to death for killing Detective Nemorin and Detective Andrews. On March 14, 2016, a federal judge again ruled against the death penalty, stating that Wilson met the criteria for being intellectually disabled.

Detective Andrews had served with the New York City Police Department for seven years and was assigned to the Firearms Investigation Unit. He is survived by his two sons, Christian and Justin. Prior to his NYPD service, he had served in the US Navy for 2 years. In 2018, the 15th anniversary of the detectives’ passing was marked by a well-attended memorial service in Staten Island.

JPCA & Newtown Historical Society will be honoring Patrolman Henry E.A. Meyer and Detective Rodney Andrews on Saturday, September 18th at 10am with a procession and graveside memorial service at All Faiths Cemetery to commemorate “Thank a Police Officer Day 2021.” We invite the community to participate with us and our special guests. Please assemble at the main gate on Metropolitan Ave by 9:30am.