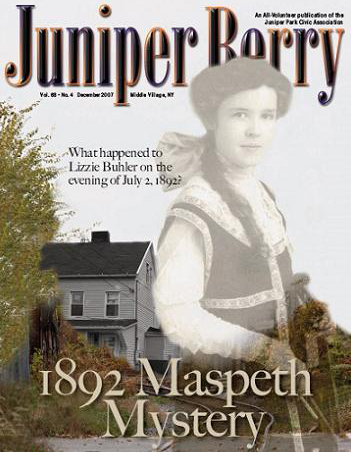

In 1892, Maspeth was a sleepy farming town referred to as being “on the outskirts of Brooklyn”. The untimely death of a popular young woman on a midsummer’s night unsettled many in the village and had them wondering whether or not her early demise was an accident or murder. For four days, the New York Times provided excellent coverage of the unfolding story. We will present their findings in three parts.

MURDER OR AN ACCIDENT

________________________________________

LIZZIE BUEHLER FOUND DEAD ON A RAILROAD TRACK.

________________________________________

SOME EVIDENCE THAT SHE WAS PLACED THERE AFTER SHE HAD BEEN MURDERED – ANOTHER LONG ISLAND MYSTERY TO BE EXPLAINED.

July 3rd – Lizzie Buhler, one of the best-known girls in the little town of Maspeth, L.I., was found yesterday morning lying dead on the tracks of the Long Island Railroad within 300 feet of her home. She had been run over by cars during the night.

It was first thought to be a case of suicide or an accident. Those theories were shattered by subsequent discoveries of wounds on the head, which, it is believed, could not have been inflicted by a locomotive, and which indicate that the girl was dead, or at least stunned, before the cars struck her. If this is so, another murder is added to the long list of those which have occurred on the outskirts of Brooklyn.

Lizzie Buhler was twenty-one years old and accounted attractive in looks and general demeanor. She found employment as a servant to private families, for her father is a poor man. Four years ago she went to work for the family of James A. Schneider, 1152 Lafayette Avenue, Brooklyn, and except for some intervals, she had worked there ever since.

For nearly a year past she had not been steadily at work. Four weeks ago some members of the Schneider family went to Lizzie’s house to re-engage her. They were going into the country soon for the summer and wanted her to go with them.

Lizzie went to work for the Schneiders. At times she would call at her home to see her parents. She was kind and gentle toward them and they thought a great deal of her.

Friday night Lizzie told Mrs. Schneider that she was invited to a dance that evening and asked permission to attend. This was granted, and she left the house. She did not attend the dance, and it is now believed that she made that statement to her employer as an excuse for going away. She was allowed a regular “evening out” and took advantage of it.

On Friday night, Lizzie went to her father’s home in Maspeth near the Flushing Avenue crossing of the Long Island Railroad. Her parents say she was more kind and gentle and pleasant than usual that evening. She spoke of going into the country on Monday with her employers, and made some extra clothing to take with her. About 10:30 o’clock she said she must return to the Schneiders.

Lizzie’s mother objected, saying it was too late to be out. Lizzie laughed and said she was not afraid. She knew the streets and was not likely to be run over at any crossings. As her mother urged her to stay, she said she had left the dishes unwashed so as to come and make the visit, and she must return and wash them. Her mother volunteered to walk with her to the street car, but Lizzie would not permit it and left the house.

The next known of the young woman was yesterday morning at 5:30 o’clock. At that time Adam Krummick, a resident of the neighborhood, came rushing up to Alonzo Kyle, the flagman on duty at the Flushing Avenue crossing of the Long Island Railroad.

“There’s a woman been run over right up here,” said he.

Kyle could not leave his post and Krummick ran back up the track. On the way he saw some members of the Breeden family, who also live there, and told them of the tragedy. They took a blanket and ran with Krummick to the place where the body was lying, on and beside the tracks, between Furman (now 55th) and Garrison (now 54th) Streets.

The body had been cleanly cut in two, and the upper part was lying outside the rails. The blanket was quickly spread over the remains. Just then a freight train came thundering down from Fresh Pond, with the engine in front, but made to stop, and ran over the remains. It cannot be told how many trains ran over them during the night.

A crowd quickly gathered, and while they stood about, the father of the dead girl was seen approaching. Some kind-hearted neighbors diverted him, and the body was taken to his home.

Coroner Emmanuel Brandon, whose office is in Newtown, took charge of the body. He did not find it necessary to remove it from Mr. Buhler’s house. He viewed it and caused an autopsy to be made by Dr. A.C. Combes.

The doctor found two wounds on the girl’s head, one of which came from a blow strong enough to break the skull. “The body,” said Dr. Combes, “was evidently lying across the rails when struck, with hips on the rail. This disposition of the body is significant in view of the fact that the autopsy also developed that Miss Buhler was soon to become a mother.”

“From the condition of the heart and lungs, I am convinced that the blows on the head were delivered some time before the train struck and ran over the body. The wounds are just such that would result from blows with a bludgeon. The force of the blows, while possibly not sufficient to cause immediate death, or perhaps death at all, were sufficient to make the girl unconscious for hours. An interested party would have found it easy, after the blows, to arrange the girl’s unconscious form upon the track. I think it is a case into which the Coroner should look thoroughly.”

Coroner Brandon will hold an inquest next Wednesday evening. The condition of the girl, as shown by autopsy, was a surprise. Everybody spoke of Lizzie in terms of the highest praise. Her parents believed in her and her employers were more than satisfied with her.

Late in the afternoon, it was asserted that Lizzie had once had a lover, and had quarreled with him. Then it appeared that another young man had lately been keeping company with her. This man’s name was given as Joseph Easer, living on Metropolitan Avenue. A call there brought forth a stout denial of attention on his part to Lizzie. She was in the habit of occasionally going to Easer’s place, which is in the nature of a beer garden, with other girls; and that there was about the place a gang of young fellows who spoke slightingly of her.

It is declared by a large number of citizens of Maspeth and vicinity that the Long Island Railroad Company is negligent in the matter of providing for the safety of people along its line. The line through Maspeth is only a short one of about two miles, and extends from Bushwick to Fresh Pond. The train runs from Bushwick, and at Fresh Pond the engine goes back on switch to the rear of the train, and backs down to Bushwick again. The engineer finds it impossible to keep a good lookout when running in this way. The engines give only one whistle when approaching curves, and none at all when approaching stations where there is a flagman.

In 1892, an unmarried mother-to-be in a small town would have created quite a scandal. Was Lizzie Buhler murdered by the father of her baby? Or was her death just an accident? More on this story in the next issue of the Juniper Berry.