A No 7 straphanger passing under the East River might hum Billy Joel’s “Piano Man” wondering who the Piano Man is. No, it’s not Vladimir Horowitz or Art Tatum. Our straphanger may be surprised to learn that the tubes he is riding through are named after the real Piano Man – William Steinway.

The Steinway Tunnel idea goes back to February 25, 1885, when a group of Queens businessmen incorporated the East River Tunnel Railway Company under the General Railroad Act of 1850. The purpose of their plan was to construct a tunnel railroad from Ravenswood, north of Hunters Point, to a convenient point in Manhattan, which would connect the LIRR directly to the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad (later New York Central).

Steinway enters the picture

Various schemes were tried and found wanting, until it was decided that a tunnel starting at Park Avenue, running directly east along 42nd Street, under the East River and ending near Hunters Point Avenue in Long Island City was the best solution. A backer was needed for this. William Steinway, founder of Steinway & Sons Piano Co., a wealthy real estate holder in LIC, was the logical choice.

Steinway also owned the Steinway and Hunters Point Railroad, which was a local horsecar line. It was his plan to operate the tunnels by electricity, which had recently been harnessed for electric traction motors.

May 1892 saw the preliminary work begin with the actual ground breaking on June 3rd, south of the southern sidewalk on 50th Avenue, between Vernon and Jackson Avenues. Shortly after the horizontal tunneling began, difficulties arose. Occasional blasting damaged property of nearby residences and businesses. On December 28, 1892, a dynamite explosion occurred, killing a workman, Nickolas Landano, and four others. Twenty others were injured, some seriously. The financial panic of 1893 and the continual flooding of the shaft caused the tunnels to be boarded up on February 2, 1893. From that time, with Steinway’s death in 1896, periodic attempts had been made to revive the tunnel project without success.

Belmont takes over

In February 1902, new life began to appear around the abandoned tunnel shafts as August Belmont, Jr. began to take an interest in the project. He was a friend of William Steinway who entered the subway construction field in 1900. By assuming the cost of building the Interborough Rapid Transit (IRT) and operating the first subway in 1904 (City Hall to 145th Street) control of the shaky New York & Queens County (later Queens Transit) and its sister company, the New York & Long Island Railroad, passed from Steinway to Belmont. The revised tunnel project became known as the “Belmont Tunnels”, although Belmont preferred “Steinway Tunnels”, so Steinway Tunnels, it was. The tunnel specifications were more in line for streetcar or small rapid transit operation. By this time with plans in place for a Pennsylvania Railroad in place, earlier plans for a freight tunnel were dropped.

On the Manhattan end of the tunnel, it was proposed to terminate the tunnels at 42nd Street and Park Avenue. At the Queens end, the tunnels were to emerge from a portal between Vernon Blvd. and Jackson Ave. Here a ramp was to be built connecting the tunnels with the New York & Queens County Railway (later Queens Transit).

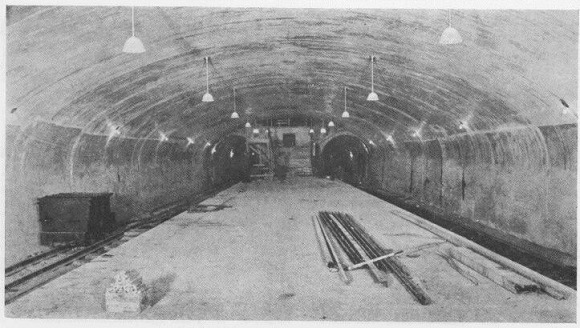

On May 16, 1907, the north tube was holed through and the south tunnel followed on August 7. Had the tunnels been completed as planned, they would have been the first subway line in the U.S., but with 15 years passing by, Boston had opened its first subway line in 1896. New York’s IRT opened in 1904.

The entire tunnel project was completed in 26 months, which was very good time. They should have been completed sooner if not for litigation by the city. The city’s objections were mainly 1) the low rate of revenue and 2) the tunnels were privately owned and operated unlike the IRT which was city owned and privately operated.

Tunnels finally open

During this period while the lawyers were carrying out legal maneuverings, other men went about their job of preparing the tunnels for service. It was decided to use trolley cars under their own power. Third rail was ruled out since it was hoped that the trolleys would eventually run on streets (a trolley-subway operation, similar to Boston’s). Fifty steel streetcars were purchased by the IRT and assigned to the New York & Queens County Railway (later Queens Transit) for tunnel service. The cars were numbered #601 to #650 and were probably the first all-steel trolley cars built in the U.S. They were purchased because they were non-flammable and safe in the tunnels.

#601 was picked for the initial test run of the line. An underground station was constructed at Jackson Avenue and Van Alst (21st Street). An official opening was set for September 29, 1907 and was attended by Belmont, the mayor and assorted officials. This trip ran through Lexington Avenue where all concerned retired to the Belmont Hotel for dinner and speeches. The tunnel became quite an attraction as the first underwater tube in New York City. Without a franchise to operate for revenue, or a company legally in existence to hold it, Belmont was stuck with a set of tunnels on his hands. In late October, #601 was removed from the tunnels and the tunnels were sealed. All fifty tunnel trolley cars were assigned to the Steinway Lines (then a New York & Queens County affiliate). They then ran on Steinway where they proved to be unsatisfactory, being too heavy for the rails. Shortly after they were all scrapped. However, #601 had its moment of glory, unaware that a chance assignment gave it the honor of being the first car to pass through an East River underwater crossing. Sadly, this important trolley car was not saved for a museum.

The Steinway Tunnels, part 2 – Revival will appear in the next Juniper Berry.

Information for this article was derived from E.R.A. (Electric Railroads Association) publications as well as my own personal knowledge of the No. 7 line.