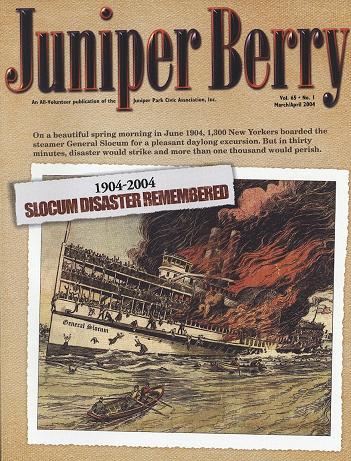

Ask any New Yorker to name the city’s greatest disaster before September 11, 2001 and invariably they offer the same answer: the Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire of 1911. That tragic event garnered international headlines as 146 young immigrant women lost their lives in an unsafe garment factory. Yet even though it is certainly Gotham’s most famous disaster, it runs a distant second to a much larger catastrophe which occurred only seven years earlier. On June 15, 1904, more than 1,000 people died when their steamship, the General Slocum, burst into flames while moving up the East River. It was the second-most deadly fire (after the Peshtigo fire of 1871) and most deadly peacetime maritime disaster in American history.

The story of the General Slocum tragedy begins in the thriving German neighborhood known as Kleindeutchland, or Little Germany. Located on the Lower East Side in what is today called the East Village, Kleindeutchland had been home to New York’s German immigrant population since they first began arriving in large numbers in the 1840s. With more than 80,000 Germans living there by the 1870s, the neighborhood lived up to its name. German fraternal societies, athletic clubs, theaters, bookshops, and restaurants and beer gardens abounded. So too did synagogues and churches. One of those churches, St. Mark’s Lutheran church on East 6th Street, held an annual outing to celebrate the end of the Sunday school year. They usually chartered an excursion boat to take them to a nearby recreation spot for a day of swimming, games, and food. On June 15, 1904, more than 1,300 people boarded the General Slocum for a day at Locust Grove on Long Island Sound.

Shortly after 9:30 a.m., the crew of the General Slocum cast off and the ship pulled away from the pier. It chugged northward up the East River, gradually increasing speed. Hundreds of children jammed the upper deck to take it all in. Like most mornings, the river was full of boats of every description – barges, lighters, tenders, and tugs. The adults talked and listened to a band play German favorites.

Then disaster struck. As the ship passed East 90th Street, smoke started billowing from a forward storage room. A spark, most likely from a carelessly tossed match, had ignited a barrel of straw. Several crewmen tried to put the fire out, but they had never conducted a fire drill or undergone any emergency training. To make matters worse, the ship’s rotten fire hoses burst when the water was turned on. By the time they notified Captain William Van Schaick of the emergency – fully ten minutes after discovering the fire — the blaze raged out of control.

The captain looked to the piers along the East River, but feared he might touch off an explosion among the many oil tanks there. Instead, even as onlookers on the Manhattan shore shouted for him to dock the ship, he opted to proceed at top speed to North Brother Island a mile ahead. Several small boats followed the floating inferno as it roared upriver.

The increased speed fanned the flames. Panicked passengers ran about the deck, unsure where to take refuge. Mothers screamed for their children, husbands for their wives. The flames, accelerated by fresh coat of highly flammable paint, rapidly enveloped the ship and passengers began to jump overboard. Some clung to the rails as long as they could before jumping into the churning water. A few were rescued by nearby boats, but most did not know how to swim and simply drowned.

The inexperienced crew provided no help. Nor did the 3,000 lifejackets on board. Rotten and filled with disintegrated cork, they had long since lost their buoyancy. Those who put them on sank as soon as they hit the water. Wired in place, none of the lifeboats could be dislodged. Even if they had, they would never have made it safely into the water with the ship chugging along at top speed.

By the time the ship finally beached at North Brother Island, it was almost completely engulfed in fire. Survivors poured over the railings into the water. Some huddled in the few places not yet reached by the flames, too terrified to jump. Nurses and patients at the island’s contagious disease hospital rushed to offer assistance. Several of them grabbed ladders being used to renovate the facility and used them to bring the survivors off the ship. Others caught children tossed by distraught parents. Within minutes, all who could be saved, including the captain and several crew, were moved away from the burning hulk.

The General Slocum left a grisly wake. The boats that followed seeking to offer assistance plucked a few survivors from the water. But mostly they found only the lifeless bodies of the ship’s ill-fated passengers. The fact that most were young children only added to the horror.

Within minutes of the tragedy, reporters from the New York World and other major dailies were on the scene. The dispatches they sent back to their newsrooms sickened many a hardened editor. Rescue workers openly wept as the corpses piled up. By the time they were done counting the bodies and tabulating a list of the missing, the death toll stood at 1,021.

With more than 1,300 people on the outing, nearly everyone in the neighborhood knew someone on the ship. As word of the fire spread, it caused panic and confusion. No one seemed to know where to go. Thousands gathered at St. Mark’s Church awaiting word about survivors. Thousands more rushed uptown to the East 23rd Street pier designated as a temporary morgue. By mid-afternoon, those not yet reunited with their family members began to lose hope. Many discovered they had lost a wife or child. Dozens learned they had lost their entire families.

At the morgue policemen and Coroner’s Department workers labored to lay out the hundreds of corpses as they arrived. Others were dispatched to scour the city for coffins. Wagons arrived laden with tons of ice for the preservation of the bodies. Outside hundreds of policemen strained to control the swelling crowds of relatives and friends, not to mention curiosity seekers, reporters, and undertakers.

For the next week, thousands paraded past the gruesome lineup of victims resting in open coffins. The better preserved were identified quickly. Some of the burned and disfigured were identified by their clothing or jewelry. The sixty-one that could not be identified – including many of the bodies recovered days after the event — were buried in a common grave. Funerals were held every hour for days on end in the churches of Kleindeutschland. These tragic scenes were punctuated by the suicides of several men and women who lost their entire families in the fire.

The story of the General Slocum made headlines across the nation and around the globe. World leaders and European royalty sent money and letters of condolence to Mayor George B. McClellan and the people of St. Mark’s. Funds poured in from private citizens and charitable groups from Rhode Island to California.

How could a tragedy of such magnitude occur within a few hundred yards of the shores of the nation’s most modern city? In the weeks and months that followed the fire, an outraged public searched for answers and culprits. City officials vowed to conduct a thorough investigation and within weeks, Captain Van Schaick, executives of the Knickerbocker Steamboat Co., and the Inspector who certified the General Slocum as safe only a month before the fire were indicted.

Captain Van Schaick came under the most intense scrutiny. Why had he failed to dock the ship immediately after discovering the fire? Why had he instead raced upriver and allowed the fire to claim more victims? Why was his crew so poorly trained? How was it that he survived when so many others perished?

At his trial Van Schaick offered plausible explanations for his actions, but the jury was not convinced. A convenient scapegoat, he was convicted of criminal negligence and manslaughter and sentenced to ten years hard labor in the Sing Sing prison. He served three years before receiving a pardon from President William H. Taft. Van Schaick was free, but broken by the horrible tragedy and subsequent legal crucifixion, he lived out his days in melancholy seclusion.

In contrast, the officials at the Knickerbocker Steamship Company escaped with only a nominal fine. This despite the fact that the trial revealed the company had illegally falsified records to cover up their lack of attention to passenger safety.

The General Slocum tragedy left a lasting impact on New York City. First, it caused the rapid dissolution of the German enclave of Kleindeutschland. Most survivors and their relatives were unwilling to remain in a neighborhood suffused by tragedy and simply moved. The steady exodus of Germans to upper Manhattan’s Yorkville begun in the 1890s now became a torrent. By the time of the 1910 census, only a handful of German families remained in Kleindeutschland. The Slocum tragedy not only consumed 1,021 lives, but took with it an entire community as well.

Second, the General Slocum disaster brought about a major upgrading of steamboat safety regulations and a sweeping reform of the United States Steamboat Inspection Service (USSIS). One week after the fire, President Theodore Roosevelt named a five-man commission to investigate the Slocum tragedy and recommend measures that would prevent an event like it from occurring again. The commission held hearings in New York and Washington, D. C. and took testimony from hundreds of witnesses and experts.

In October 1904 it issued a scathing report that placed most of the blame at the feet of the USSIS. Dozens were fired and a complete re-inspection of steamboats ordered. Not surprisingly, the new inspections turned up widespread safety problems, from useless lifejackets to rotten fire hoses. The result was a long list of recommended reforms, including requiring new steamboats be equipped with:

• fireproof metal bulkheads to contain fires

• steam pipes extended from the boiler into cargo areas (to act as a sprinkler)

• improved lifejackets (one for each passenger and crew member)

• fire hoses capable of handling 100 pounds of pressure per square inch

• accessible life boats

All were subsequently enacted, leading to dramatic improvements in steamboat safety.

Remarkably, the Slocum tragedy rapidly faded from public memory, to the point that it was replaced as the city’s GREAT fire just seven years later when the Triangle Shirtwaist factory burned. There were similarities between the two fires – both involved immigrants and mostly female victims and both aroused public wrath. But the Triangle fire’s death toll was 85% lower than the Slocum just seven years earlier. How then did it become the fire of fires in New York’s (and the nation’s) memory?

Two factors begin to explain this remarkable legacy. First, there was the context. The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire occurred at a time of intense labor struggle, especially in the garment trades. Only a year before the shirtwaist makers had staged a huge strike for better wages, hours and conditions. Now 146 of them lay dead. There was no question about who was to blame.This conclusion was reinforced when the public learned that the factory owners had locked the exits to keep the women at their machines. Second, the onset of World War I eradicated sympathy for anything German, including the innocent victims of the General Slocum fire. By the 1920s, as the Triangle fire became firmly entrenched in the American memory, all that remained of the General Slocum fire was a small, annual commemoration at the Lutheran cemetery in Middle Village, Queens.

Writer is the author of several books, including his most recent, Ship Ablaze: which tells the extraordinary story of the burning of the steamboat General Slocum, the deadliest day in New York City history before September 11.