When asked to write an op-ed on the recent bail reform measures, realized as an addendum to budget bill A02009C under circumstances less than desirable for proper civic discourse and public review, I had admittedly already formed an opinion on the topic based on the dubious approach to implementation.

Presented with an array of editorials touting the merits of bail reform, I realized another look at the relative value of the program itself, vice the suspect nature of implementation, was in order. Both local representatives Senator Joseph Addabbo and Assemblyman Brian Barnwell voted in favor of this bill for reasons that we are left to guess for want of their ability to speak to the merits of the program in any detail. There is a considerable amount of opinion driven commentary in the local media explaining how this change will actually make us safer overall as a state.

Barring any verified data that has yet to be provided for public review, I find this all hard to believe. Disregarding the intention of the bail reform measures for a moment, it is counterintuitive to plainly state that the end state of releasing accused criminals back into our neighborhoods is going to lower the crime rate.

Let us first look at the intention of bail: submitting a payment in order to be released from jail is intended to provide financial disincentive for an individual who has been charged with a crime to return for their court dates. Defendants are constitutionally protected by the Eighth Amendment against excessive bail. In New York, a judge is able to consider a variety of factors when setting bail, such as prior criminal history, whether or not someone has previously returned to court and the charges against the defendant. Bail is used as collateral and returned to a defendant at the end of their criminal proceedings. If a person cannot post bail, they are incarcerated up until and throughout the duration of their trial. If a defendant flees after posting bail, he or she forfeits that money.

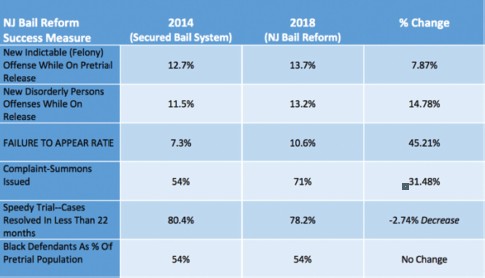

New Jersey was one of the first states to go down this road and, if you believe the rubbish the one-sided media feeds us, it looks like all is working well. However let us look at some of the actual statistical data provided by the American Bail Coalition.

While the report issued by the Courts is woefully inadequate in many respects, especially given all of the resources they were provided to procure new computers and programming to make this process easier, it does illuminate some interesting statistics. Other than a continued and now slowing decline in jail population, the results are not favorable.

It is imperative to understand that the State of New Jersey increased the use of a summons 71% instead of an arrest when reviewing all cases in 2018, up from 54% in 2014. In other words, in 17% of total criminal cases there was not an arrest in 2018, where there would have been an arrest in 2014. That represents 22,951 people that were not arrested in 2018 that would have been in 2014. If any gains have been made, then this is most certainly the only reason that it could possibly have had an impact. Yet, this has nothing to do with “cash bail.” This is a change in arrest procedures.

More importantly, this could have been done for free, and no constitutional amendment was required. The new system performs worse than the old money bail system being run in New Jersey in 2014. The rate of failing to appear in Court increased by 45.21%. The rate of disorderly conduct offenses being committed while on bail increased by 14.78%. New indictable offenses while on pretrial release: a 7.87% increase. Let us not forget that the bail reform act was called the “New Jersey Bail Reform and Speedy Trial Reform Act.” Except, according to the Courts, the cases are now less speedy than before according to what they perceive to be an important measure. The number of cases resolved in less than 22 months dropped to 78.2% in 2018 from 80.4% in 2014. In other words, the need for speed was not the reality. Furthermore the jail population decrease is pointed to as another success of bail reform. Except the pretrial jail population had been dropping by greater percentages than it did in 2018. There are many causes for this general drop in New Jersey’s jail population as we have previously noted. For example, the pretrial jail population dropped by 20.7% in 2016 as compared to 2015. 2016 was the last calendar year prior to the enactment of bail reform on January 1, 2017. The pretrial jail population in 2018 declined by only 13% as compared to 2017.

Governor Andrew Cuomo has been quoted saying “There's no doubt this is still a work in progress, and there are other changes that have to be made,” “We’re going to work on it because there are consequences we have to adjust for,” The Governor told a group of the city’s influencers at the Association for a Better New York that he will work with the Legislature to revamp the law.

Unfortunately, there have been many cases in the news recently providing direct examples of how this initiative is both a failure in policy and a concern for the continued safety of our communities. Take, for example, the case of Tiffany Harris, a 35-year-old woman in Brooklyn who allegedly attacked three Jewish women in Crown Heights, went to jail and then was released, only to allegedly assault another woman in Prospect Heights the very next day.

More recently there were six drug kingpins arrested with more than $7 million worth of fentanyl and heroin in the Bronx yet a Judge was forced to set them free. There is no shortage of similar stories in the short time we have been subjected to this absurdity.

Our own Brian Barnwell has asked the chamber’s bill drafters to craft legislation that would give Judges the authority to remand defendants based on factors that include criminal record and their perceived danger to the community. It’s unclear just how soon the Legislature will make changes. Keep on top of our elected officials and impress upon them the importance of representing their constituents’ concerns rather than continued partisan tribalism. A number of lawmakers have already introduced bills, but they will have their hands full for the foreseeable future – as will the police as repeat offenders continue to be released before their reports have been finalized.