– Some of the Dangers Pedestrians were Subjected To –

– Halcyon Days for Local Anglers-

One of the most noted of the landmarks, so called, of Brooklyn, composing very much of the area included in the northwestern division of the Eighteenth ward, is being rapidly changed – obliterated would, perhaps, be a better word – on the topographical map of the city. Look upon a chart of Brooklyn of today and where a decade ago was a large, semi-circular area, with striated lines indicating indicative of a swamp and depression, the inquirer will find that the surveyor has been there and run his parallels so that there are predictions of streets and avenues all over it. But how he “ever got there” is a question that may never be answered. This marsh of upward of two hundred acres is rapidly becoming the center of important lines of trade.

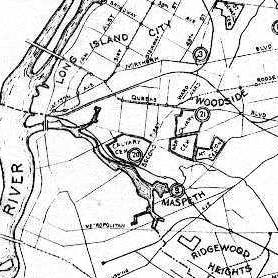

The area to which reference is made is that large amphitheatrical space once undoubtedly, and not many moons ago at that, submerged and of sufficient depth to admit craft of considerable draught and tonnage, to which the name of the Maspeth meadows has now been given.

Newtown creek is today of sufficient depth, even to the Penny Bridge, to permit ships drawing ten and twelve feet to float upon, and where the bay that once was near its head – later swamp and now with every prospect of becoming solid ground – had a surface of no means extent. It must have been a delightful summer resort for the papooses of the aborigines and the mosquitoes. The old shorelines may in our time be traced. They started from the creek and taking a southwesterly course swept around at or near the surveyor’s lines of Morgan avenue to Johnson and thence eastwardly to the Maspeth heights, and again northwardly to the banks of the creek. Even now it is not advisable to make oneself too familiar with the area indicated. It has within it hundreds of sinks and pits which if anything living falls into, man or beast, it is certain to perish. Three summers ago a woman of the chiffonier class – a German or Italian – while gathering foul rags and other seemingly valueless things from the dumps that were carted there, and while actually surrounded by her companions, perished almost within reach of their hands. They were near the northern side of Johnson avenue, not far from a sink. The woman in reaching for a bone lost her balance and tumbled into a hole. She made a desperate struggle to reach the edge of the pit but failed and her friends could not seize and draw her to firm ground. Exhausted by her struggles she gradually sank beneath the surface of the black, poison charged, putrid waters.

All this, it should be remembered, was within a rod of the high natural ground upon which Johnson avenue has its parallels.

The incident is simply recalled to give the reader a faint idea of the dangers that await an adventurer in this unpleasant and very deceiving section of the Eighteenth ward. But it is all being changed. It is a stupendous undertaking, yet by the close of the present century, that is, ten years or so from now, it will puzzle any but an old stager to indicate the outer semicircle within which the Maspeth marsh lay. Even now it is matter for no little surprise in many ways. Among old Brooklynites, those of them who have grown from childhood up to gray beards marvel at the changes time, energy, engineering skill and capital have wrought therein.

At the foot of Grand street, where the strong tides of the East river flow inward and outward, and from which point to the estuary of Newtown creek is nearly two miles, a person who leaves the ferry and rides or walks as he supposes landward, is apt to be astonished upon reaching Bushwick avenue at Grand street, at seeing the masts of many a tall admiral before him. And he looks vainly for a moment for the water upon which they ride. Of course, when he turns his eyes northwardly he finds that the creek from which he supposed he had gone had actually swept with a great trend to the south and west and was again at the fore as the feeder and at the same time the drainer of the upper creek and the marsh.

Further, there was a time, and that within the present century, when a man entering with a skiff the stream that drained what was called Johnson’s wood could make his way through the water courses that cut into the once low grounds of the Nineteenth, Sixteenth, Fifteenth and Eighteenth wards to the marsh and thence, sinuously to the creek by way of its many natural ditches. All this land has been changed in its aspect. Topographically speaking it is not as it used to be. Many of the streets in the wards named have been graded up in some instances from fifteen to twenty feet. Moore street and many parallel streets in the Sixteenth ward stand several feel higher than they were in the year 1845. In 1850, the Johnson wood, bounded by Broadway and Flushing avenue and Hewes street, a great triangular space, partially covered with bushes and trees of second growth, was low, swampy, miry and snake infested. It is now filled with dwellings and factories and it is otherwise so changed that the boys of forty or fifty years ago (grandfathers now), when the eastern district was the village of Williamsburgh, who used of a Sunday invade the wood and find sport in killing garter snakes, are now half persuaded that the past was a dream to them and there really was never a spot known as Johnson’s wood. Broadway has been lifted from its bed many times between Union and Flushing avenues and even today, when the rains fall upon it with little moderation or the tide is unusually high, it is flooded to and upon the sidewalks. At Union avenue, the grade of Broadway was raised ten feet.

All this is mentioned to give the reader some idea of the condition of the grades of the wards named five decades ago. It is also intended to show that there was a time, since the glacial period, to be sure, and while possibly the Eighteenth century was yet young, when the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, Fifteenth, Sixteenth, nearly all of the Nineteenth and a third of the Eighteenth wards were surrounded by water – practically an island.

But of Newtown creek and Maspeth meadows? Thirty years ago the waters of the creek were as pure as those of the sea and the bayous were favorite resorts for fish such as sport and grow fat and usable in tide waters. In these halcyon days of the local anglers it was a pleasure for them to enter the creek and cast their lines, with barbed hooks charged with enticing bait. But vandals, in the shape of chemists and oil distillers, came along and seizing upon the banks of the inlet erected great laboratories and refineries and distilleries, and soon the waters were made unfit for even eels to wriggle in. The disciples of Isaak Walton mourned the inroads of manufacturers and commerce and sought elsewhere for the prizes the poison impregnated waters refused them. Bismillah, but it was a sad day for the fishermen!

As for the swamp, the changes which it has undergone are really wonderful and yet but little comparatively has been done. Canals have been cut through it, in zigzag fashion, railroad tracks, with their heavy embankments, bisect it from end to end, and from center to circumference coal and lumber yards have been measured off filled in and piled; docks have been built, some of them in the very heart of the marsh; convenient highways, including Maspeth, Metropolitan and Grand avenues have been paved and dozens of streets, originating in the Sixteenth Ward, have been extended to and through it. Among them are Scholes, Stagg, Ten Eyck, Meserole and Montrose, all parallel and north of Johnson avenue. Then again, there are a dozen or two streets and avenues that run at right angles to them and which will eventually find their “feet” laved by the tidal ebbs of and flows that enter into and retire from the creek.

It must not be supposed because of the existence in part with the sure and almost immediate extinction of the great morass that the country surrounding it is forbidding. Quite the contrary, within sight of it is the old one story frame schoolhouse (now occupied as a little store and residence by a German family) in which the founders of the Harper printery were, with David and George Bruce, the sons of the first firm print the English Bible in America, and whose type foundry is still flourishing in Chambers street, near Center, New York, were educated. And not far from it, near the headwaters of the inlet, stands yet the residence of the builder of the Erie canal, Governor DeWitt Clinton.

It was a boy of 14 that James, the elder of the Harper brothers, trudged over the Maspeth road one morning in May nearly eighty-five years ago and finally, upon reaching the East river, crossed it to New York, there to seek his fortune. He found a place in a printing office where, being apt and attentive, he was in good time made master of the art preservative of all arts. His brothers followed him and were also inducted into the mysteries of the typothetae; and after a time, being industrious and prudent as well as enterprising, they got together a small office. This plant, as the years came and went, like shadows upon time’s dial, increased in volume and value. The founder became a mayor of New York. Finally, all the brothers passed away to the summer land, but their descendants now not only enjoy the business they built up, but the millions they had accumulated.

As for the Bruces, George and David, they were famous in their day. They were of Scotch birth. They, too, were masters in the art of printing. As has been said, they were so enterprising as to undertake the really giant work of introducing to the American public an American printed Bible, without an error in it. It was read for errors eight times and revised as many. They were not bankrupted, but they confessed, when it was on the market, that it would have been prudent in them to have let the scheme alone. George Bruce was the first to introduce stereotyping to the American printing office. Before his time, the stereotype plate, because of its unevenness, was all but valueless. He invented a machine by which it could be made of uniform thickness and evenness, desiderata that greatly cheapened printing. The Bruces finally drifted into the type founding business, and in this they made money. David particularly, for George was more of a philosopher than a shekel gatherer. When the former shuffled off this mortal coil, about twenty years ago, he was rated a man worth many millions. His nephew, David Bruce, is yet living and has to the credit side of the ledger of life upward of 90 years. He is one of the old Maspeth scholars – a schoolmate of the Harpers. He resides on South Fourth street, eastern district, and is for a man who is so very old as lively as a cricket. Like his father, George Bruce, he is an inventor. Among a dozen of other contrivances he got up the type casting machine, which revolutionized type making, earning millions for founders but not one cent for himself. He also invented a type dressing and rubbing machine, which is today in the possession of the heirs of the Connor founders. To his genius is also due the thousands of type faces which make beautiful the printer’s art. These children of Maspeth are merely specimen bricks, so to speak, drawn out from the head waters of Newtown creek and the treacherous morass, when New York City was scarce above the city hall, and the Brooklyn we live in could not count a population exceeding five thousand residents, including Indians and negroes.

It is strange, but it is nonetheless remarkable for all that, that the swamp which, even at this hour is not safe except by boat or upon the embankment of the Manhattan beach railroad to venture into, at an early date in the history of Long Island was not a hindrance to the settlement of the dry lands contiguous thereto. Indeed, so very numerous were the settlers that for their spiritual needs the old Bushwick church nearby was organized as far back as 237 years ago. The prayers and the sermons were made in good, honest Dutch, and even at this day a sermon in that tongue, but at distant intervals, is heard. The old Bushwick is a reformed establishment now. The ancient schoolhouse –whose teacher, one hundred years ago, when the Harpers and the Bruces and many others whose names are inscribed on the rolls of civic fame, was Louis Marquand – is yet in fair order. Marquand was a splendid scholar. As a linguist he was not surpassed in his time. He read with facility in many languages, modern and ancient, and he boasted the grade of highest scholarship from the University of Cambridge, England. He was a man of naturally fine mental powers, but he had a weakness. His thirst was unappeasable. His idea was that water was an excellent thing in which to float ships and make tea for women and children, but by a gentleman and a scholar only the richest and oldest distillations of brandy should be taken into the stomach.

Another institution of no little note once adorned the vicinity of the Maspeth meadows. This was Peter Cooper’s great glue factory. It was a stupendous concern in its day and is not a secondary affair even now. Mr. Cooper put the building upon the side of a hill, and from any of its openings a fine view, if the weather was not foggy, could always be commanded of the morass, and when the wind was in the right quarter the weight of the glue was greatly added by the adhesions of millions upon billions of mosquitoes. Peter Cooper was a shrewd man, and the fact that the swamps in the vicinity of his glue works were breeders of the posts may have induced him to put a plant there. It was fearful for the workmen, and is measurably so today. But as the dirt of the city is being carted and dumped into the bogs by the thousand square yards every twenty-four hours, a good arithmetician, by measuring the extent of their surfaces and their depths, may reach the possible time where there will be firm land throughout the entire area, dumping being no longer a necessity.

When that day comes the Maspeth swamp will be no more known among men. The people of the present age who have already forgotten the localities of low, wet grounds that have been graded up, may have a dreamlike recollection of it, and those who walk the streets intersecting it in the future time will imagine that it was always solid, and that no poor ragpicker could have been suffocated in its muddy, perilous, slimy waters, and that, too, within a very few feet of the really high ground through which Johnson Avenue passes, from Bushwick hill to Maspeth heights.