Foul Waters Once a Favorite Resort of Fish – Landing of New Netherlanders at Hunter’s Point – Brook School House and Pedagogue Tarquand – Indian Names – Lord Howe – David Bruce – DeWitt Clinton – John and James Harper. Refineries, Distilleries and Other Industrial Works of Today.

Of the 600,000 residents of Brooklyn whose happy lot it is to live south of the little shallow basin that once was known as Bushwick Creek it is not an extravagant estimate to say that quite 85 percent of them have an indifferent idea of the all but putrescent stream, navigable and the center of important industrial interests, which bounds the northern limits of the city – a stream often mentioned in the Eagle under the name of Newtown Creek. There was a time, and that within the recollection of men of middle age, when this creek, the waters of which are today poisoned with the overflow of the waste which comes from the great chemical and other works that line its bank, was the home of fish of diverse forms and flavors. It was the resort of those who delighted in placatorial recreations and rarely were those who cast their lines in its pure waters disappointed of a goodly catch. It had peculiar attractions in this respect. While the creek for nearly three miles inland was a sort of paradise for fish of the ocean kind, above that point the brooks were inhabited by freshwater creatures, a tradition being held by many of the oldest inhabitants that trout of orthodox size and weight once sported in the cool pools that were formed by the outflowings of the springs near Tarquand’s school house. Now, nor for the past two decades, not an inhabitant of the deep is there to be found in it from source to estuary.

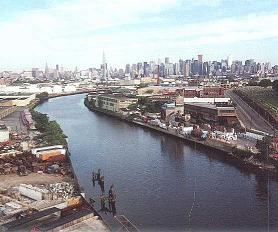

Greasy, foul smelling, as are the waters of Newtown Creek – a poisoned tideway from end to end – winding in and out in most tortuous fashion, an uncovered, navigable sewer, it is, nevertheless, a channel which Brooklyn and New York could not well do without. Millions of dollars are invested in the plants established on its forbidding and unpicturesque shores, and hundreds of thousands of dollars of marketable products are annually carried from them to be finally distributed at great profit throughout the world. Dark and thick and sullen as is the tide of this highway, and unpleasant to eye and nose its appearance and odors, it yet gives much “light” to human kind. It is the fountain head of many excellent things – mainly chemical results of the viscid rock oil, which are there manipulated by experts in the art of extracting delights from abhorrents, things beautiful from substances ugly, and enticing perfumes which the most sensitive of desire from crude native mixtures; and to these we may add what chemists designate as “nascent gases,” the smell from which is apt to sicken any ordinary stomach.

Uninviting as Newtown Creek is to the casual visitor it was once, apart from its attraction as a fishing ground, a desirable resort for the inhabitants of what is now designated “the metropolitan district.” We propose a passing reference to its history, with an allusion or two to its topography added.

Newtown Creek, which at present is navigable for vessels of about a hundred tons as far inland as three miles, or to Grand street bridge, was known to the aborigines as Mespeachtes, which the writer freely translates the “waters of the Mespat” or Mespacht Indians, who on the advent of the whites occupied the region lying from the present town of Maspeth eastward, to which they had given the name Wandowenock.

When the people of New Netherlands ventured upon an exploration of Long Island a small party landed at the peninsula known to us as Hunter’s Point, which they found well-wooded, the trees being old and large, and when they adventured to the interior where swings the present iron structure generally designated the Penny Bridge, they found magnificent groves on either side of the creek stretching southward and northward as far as the eye could reach. These bold Dutch explorers pronounced the land “goodly.”

The region all about today is denuded of its forest growth, and the soil has a sandy, barren aspect that gives faint promise of reward to the agriculturalist. Looking eastward still the adventurers perceived the arbor crowned heights of Wandowenock and rejoiced, but for some reason unexplained by historian or tradition they never possessed themselves of the territory. And it is a curious fact that while the Dutch were yet masters of “Nieuw Yorke” then “Nieuw Amsterdam”, a company of Englishmen journeyed unmolested by the Hollanders to the Mespeachtes, and navigated their way to the village of Mespats, or Mispats, now incorrectly written Maspeth, and on settling under patents issued to them in seversity in the year 1652, by the renowned Governor Stuyvesant, struck from their vocabulary the Wandowenock of the aborigines by giving the town land the name of Newtown, and Mespat or Mispat that of English Kilns, that it might not be confounded with Dutch Kilns, which was then even a village established a third of a mile north of the creek and within gunshot of the East River. Dutch Kilns is now within Long Island City. It is, however, in a moribund condition, annexation to ex-Mayor DeBevoise’s bailiwick having mortally hurt its growth. In fact Dutch Kilns is a “finished town” and may with propriety be “fenced in.” The English settlers at English Kilns, living quietly under the jurisdiction of their Dutch rulers – frugal, industrious, sober people were they – a large percentage of them Friends after the order of George Fox – so please Governor Stuyvesant, that three years subsequent to the settlement of Newtown he issued another series of patents, or ground briefs, as they were called, in which he conceded grants that were then esteemed unprecedentedly liberal. In 1656 a movement was made by the Newtown and English Kiln residents to obtain from the authorities permissions to found a town at the head of Newtown Creek, for “purposes of general trade and other benefits.” Governor Stuyvesant readily assented to the prayer of the petitioners, and ordered the “Surveyor General to survey the ground at the head of Mispat Creek, and lay out streets and make such other comfortable disposition as may be found necessary.” The site of the proposed town was fully determined on and a name given (Arnheim) to it; but for some reason, and upon this history and tradition are again silent, the surveys were never made.

Upon the expulsion of the Dutch an English regimen was stationed at Newtown and English Kilns until the near close of the Revolutionary War. The inhabitants, all of direct English descent and “filled with British sympathies,” were regarded by the partisans of the Continental Congress as “black hearted Tories.” It is certain they were and are to this day exceedingly conservative. Not only did they give aid and comfort to the enemy at the time of the Revolution, but it has been charged against them that they aided and abetted the English during the War of 1812. General Lord Howe, up to the termination of hostilities and the declaration of peace between the United States and Great Britain, owned a very handsome property at Maspeth, and when not engaged in the exercise of his profession resided there, of which place he appeared extremely fond.

It was also the home of DeWitt Clinton, the great Governor of New York and the builder of the Erie Canal. Governor Clinton appears to have had a mania for canal building. In the year 1809 he commenced an agitation which had for its object the construction of a navigable waterway from the head of Newtown Creek to the that of Flushing Bay, which he held would, even in his time, prove of advantage to the people. It appears that there is only about three-fourths of a mile of land between the heads of the fresh water streams (fed by plentiful springs) which have had their entrances at Newtown Creek and Flushing Bay. The cost of cutting through the land that lies between the springs and the deepening of the channels of the creeks would, measured by the importance of the whole work, be trifling. The ground is soft – a sandy loam – there being no rocks in the way. It was claimed that when the tide water was permitted to flow through the canal from creek to bay and from bay to creek, navigation would be greatly shortened, the low grounds drained and the waters of Newtown Creek made pure. This cut would make the site of Long Island City an island. That the scheme of DeWitt Clinton survives, it is only necessary to remark that the canal question is still discussed by the Newtowners and less than two months ago a public meeting was held in their village to see if measures could not be taken looking into the vigorous promotion and prosecution of the work. It may here be added, while discussing the Newtown Canal question, that the late Stephen Waterman, of this city, as far back as 1845, proposed connecting Wallabout Bay with Newtown Creek by a canal to be constructed through the low lands of the Sixteenth and Eighteenth wards, its estuary on the creek to be placed where the landing near the Grand street bridge now is. The scheme fell through, but it is the general impression that the inhabitants and property owners would be happier today than they are if the enterprising captain’s scheme had been carried out.

This recalls a little incident which may be related. Through what was known as Johnson’s woods ran a freshwater stream (it was included in Waterman’s canal line) on which excellent water cresses grew. One pleasant day the late David Bruce, the senior partner and founder of the firm of Bruce & Brother (George) now the property of the son of the junior member, a house which has the credit of printing and publishing, at their own expense, the first Bible of American manufacture, the English edition until then holding the market – one day David Bruce testing the cresses resolved on transporting some of the plants to the creek at Maspeth. The cresses grew and bade fair to equal if not rival those of Johnson’s woods – which lay between Broadway and Flushing avenue, and north of Union avenue. Unfortuantely, Governor Clinton, while walking near the creek, espied the plants, gathered them, and on taking them to his handsome residence, which yet stands in a grove near the head of the navigable stream, made a meal of them. Mr. Bruce, nothing daunted by this mishap, the following year planted the cresses liberally and they grew abundantly, and this day the peppery plant contributes largely toward the support of the many families living in the land of Mispats, who gather and sell it for the delectation of gourmands.

It is said no man was more unpopular at English Kilns than Governor DeWitt Clinton, who, in all the rest of the commonwealth, was the idol of the people. This unpopularity arose from his progressive notions. His neighbors were almost insanely conservative, and hated new fangled notions and inventions, and when he brought to his farm an improved plow, it was decried an unnecessary innovation, if not “ungodly,” and bitterly so by a shoemaker, names Burnett, who was a veritable Thomas Didymus. The new plow had two handles, an iron cutter and mold board and other contrivances. It worked well, Clinton was delighted with it, and recommended it to his neighbors who, however, persisted in holding “to the plow of their fathers,” a crude and inefficient contrivance, consisting of a single stick for handle and a wooden mold board and “nose.” The Maspeth farmers, sneer as they might, could not shut their eyes to the advantages of the plow which their fathers never saw, and after awhile, to the secret delight of the Governor, they sneakingly adopted the “invention,” and let the antediluvian one go to rot.

Did space permit, many similar anecdotes, personal to DeWitt Clinton, and never published, might be told such as the battle of his Mexican bull, a harmless brute, with that of the shoemaker Burnett’s horned one, reputed a curious creature, and which he killed outright.

We mentioned above Tarquand’s School. As several prominent citizens of Brooklyn and New York had in their very youthful days been pupils at this school a few lines may be devoted to it and its principal. The building was of wood and erected on posts set low in the ground, where the fresh water of the springs from the higher lands of Maspeth empty into the salt tide of Newtown Creek. It was generally known as the Brook Schoolhouse. In the year 1808 Mr. David Bruce was introduced in New York to an English gentleman named Paul Leonard Tarquand. The parents of this gentleman were French, and they bestowed on him an education that would have made him prominent in any part of the world but for one unfortunate habit. He was greatly given to the use of spirituous liquors, and when not employed at his duties as a teacher, he devoted himself to the not difficult task of getting drunk. Tarquand was a splendid linguist, a superior mathematician, widely read as a historian, a reliable surveyor, a superb draughtsman, a finished musician and a not indifferent portrait and landscape painter. Of course, Mr. Tarquand was poor. Mr. Bruce invited him to his residence at Maspeth and finally induced him to take charge of the Brook School, at a salary, however, that was more liberal than the trustees of the district were wont to pay – the difference came out of the celebrated type founder’s pocket. Tarquand made his school quite famous. He was an undersized, corpulent, rosy faced, good natured gentleman when sober – when “under the weather” he was irascible and filthy. Among his scholars were John and James Harper, the founders of the great publishing house of Harper Brothers, Franklin Square, New York, and David and John Bruce, sons of the type founder. Of these only David Bruce survives. He is now in his 84th year, but is hale and hearty, and bids fair to be a centenarian. Many stories are related of this pedagogue. Tarquand died at his post, and the house in which he reigned as pedagogue is now occupied by a gentleman of Teutonic aspect, who sells beer by the schooner to the thirsty.

Eighty years ago the dock near where the old school house stands was the place where the farmers of Newtown and other near parts of Queens county sailed for New York in small boats laden with garden truck, and it was there that the people of English Kilns, Newtown and hamlets contiguous gathered to gossip and smoke their pipes. It was a busy point. It sleeps now. Every Saturday, Governor Clinton, Mr. Bruce and other prominent citizens would land there on their return from their week’s absence in New York and remain over Sunday. It was no joke in those days to journey from the city, which was “reckoned” nine miles distant by water.

Returning to Mr. Burnett, the Quaker, who was a man superior to the “new fangled notions” of his time, upon being informed by Mr. Bruce that he had a few days before, while in New York, seen a vessel large enough to hold a hundred persons, move through the water without the assistance of sail, or pole or oar, he unqualifiedly doubted it.

“But, Mr. Burnett,” persisted Mr. Bruce, “it was propelled by boiling water!”

“I doubt it, sir,” said Mr. Burnett.

“I tell you I saw it!”

“I doubt it.”

“I was a passenger and am acquainted with the inventor, Mr. Fulton!”

“I doubt it, sir,” said the Quaker with increased emphasis.

“Well, well, Mr. Burnett,” exclaimed Mr. Bruce, “you are incorrigible. Now, if you were on the boat and saw it move and was carried, say from the Whitehall Landing, in New York, to our English Kilns’ dock by the use of steam, what would you say?”

“What would I say, sir? Like an honest Christian, which I hope I am, I would doubt it! Find me authority in the Holy Scriptures for the moving of a vessel or ship by the aid of hot water and I’ll no longer doubt!”

The good old Quaker lived to see not only the general adoption by his neighbors of the plow introduced by DeWitt Clinton, but the ship without sail or oar or any external appliance glide over the Bay of New York and even invade the waters of his own Mespeachtes.

The channel of Newtown creek is undoubtedly much shallower than it was fifty or even thirty years ago. An old dame, a member of the Society of Friends, who departed this life twenty years ago, informed the writer that in ante-revolutionary times – indeed long before war between the colonies and the mother country was thought of – she remembered seeing a large man of war, the Asia, carrying many guns and men, at anchor near where is now the Penny Bridge, and the open spaces on the shores were covered with the white shirts of the sailors, who, upon washing them, had spread them out to dry and bleach. There could now be no vessel of such tonnage as a war ship, displace any part of the creek. Tugboats and sloops and other small craft only can get up to the Grand street bridge and for the present that suffices.

The name English Kilns was changed about forty years ago at the insistence of Judge Furman, who died in 1865, we believe, to its aboriginal appellation. Unfortunately, he neglected to consult authorities on the Indian nomenclature of Long Island, and wrote the word Maspeth, which is not aboriginal and had no meaning. It should be spelled Mespat, which was the name of the village inhabited by the Indians in that vicinity and also the name of the tribe. It is allowable to write it Mespat, Mispat, Mespacht, or Mespeachtes, the original name of the creek, but never Maspeth.

The chemical and other works on and near the creek are, many of them, large, some occupying several acres. Among the more prominent structures may be mentioned the Cooper glue and Nichols & Co.’s chemical works, constituting in the number of buildings what would, if occupied by families, elsewhere be regarded a good sized village, where enormous quantities of sulphuric and muriatic acids and oil and vitriol are made. Then there are phosphite factories, distilleries, varnish and japan works. But, more important than all else in the magnitude of the business, the capital invested, the necessities met and the men employed, are the establishments of the Standard Oil Company. It is wonderful the secrets chemistry has wrung from rock oil. In its crude state, just as it is pumped from the wells, it is shipped to the works of the company, which line the shores of the creek, and there by distillation, pressure and other treatment are taken from the dark and viscous and uninviting mess oils of varying densities and illuminative qualities – oils for the lubrication of all kinds of machinery, some flue enough for the works of the most delicate watch, and others suited to the heaviest iron wheels and cogs and ratchet, where heat and friction are intense and constant lubrication imperative; Vaseline and other medicated preparations for the hair and cuticle, including soaps, into which it is introduced, forming the essential parts thereof; naphthas and lighter volatiles; anilines, superior in their tint, and more durable than those obtained from indigenous and other vegetable formations; coke, porous as sponge and light as cork, but when submitted to combustion giving out intense and durable heat; paraffine, both yellow and white. The last named is an exceedingly beautiful production. It is translucent as the finest and most delicate porcelain, and is in great demand abroad for many uses, particularly in the fine arts. Other productions always commercial in demand are obtained from petroleum, and experts in practical chemistry aver that they have not reached the end of the story or of the wealth that lies hidden in rock oil, and which, when properly – that is, scientifically – treated, it readily and freely yields.

It is not an inviting field to go over – a journey up and down Newtown Creek; that is, it is not picturesque. The water is covered with a scum that gives out a faint, offensive odor; the banks are bare of trees and lesser vegetation; the clear air is often filled with a dense, sticky smoke, that, lighting on the person, is apt to make the face and the hands grimy and the shirt collar black with minute spots, and when the grease rendering and bone boiling houses are at work – and it is said they often have their fires lighted at night, when work is surreptitiously pushed to completion before those who are at rest awaken with the returning light – the atmosphere is simply sickening. But what shall be done? There is no industry, no enterprise pursued at Newtown Creek, however obnoxious to the sense of smell, or sight, or hearing, or health it may be, but what is needed and must be pursued somewhere, and if it cannot be on Mespeachtes it will afflict us somewhere.

The works of the Standard Oil Company are not confined to the creek we have so often named. The commence at the foot of North Tenth street, E.D., and extend to Bushwick Creek; and again they will be found – Pratt’s refineries are we speaking of – on the north side of the Seventeenth ward, before the principal ones are reached, on the very confines of Kings County, where, also, are those of the Home Light Company, all, including Hogg’s and Devoe’s, parts of that “tremendous whole” whose body is the Standard Oil Company.