A Look Back at the History of the Queens Site and its Founding Family

Atlas Terminals has long been a substantial, but somewhat mysterious, presence in Central Queens. Companies located in the 20-acre industrial park have employed many of its Glendale-Ridgewood-Middle Village neighbors, but other members of the community have had few reasons to explore its territory. The industrial property’s history mirrors the history of its neighborhood and New York City, as it has grown and adapted to changing times.

Atlas Terminals was founded in 1922, when Henry Hemmerdinger, a 42-year-old rag merchant from Brooklyn purchased a largely-vacant tract of land at Cooper Avenue and Dry Harbor Road (now 80th Street). Atlas’ history, however, begins earlier when Henry came to the United States as a young child with his father, Morris.

Morris’s career was typical of Jewish immigrants of his day. He came to New York in 1888, succeeded in spite of limited schooling, and established a business buying fabric scraps from the garment trade and selling them as “waste” to other industries. Among his customers were manufacturers who used the inexpensive waste as rags to wipe up spills, and upholsterers who processed the waste to make stuffing. Eventually, Morris saw the value of processing the waste himself. So when he had accumulated sufficient capital, he opened his own factory and named it Atlas Waste Manufacturing Company, Inc.

After Morris’s death in 1907, Henry took over his father’s business. In 1913, Henry met his future wife while buying shoes in the new store in his Brooklyn neighborhood. There he met the proprietor’s daughter, Molly, who had just arrived from their hometown of Greenport, L.I. to help her father in his new venture. Molly and Henry were married within a matter of months. Their only child, Monroe, was born in 1917.

In 1921 the young family moved to Forest Hills Gardens, the first Jews to buy a home in the neighborhood.

Soon after, in 1922, Henry purchased a tract of land in the heart of Glendale. At the time, the area was still quite rural, with the vast majority of streets just dotted lines on surveyors’ maps. What Henry acquired was undeveloped land with one old farmhouse that faced Cooper Avenue and a few industrial buildings that had been used for a time to produce the first underwater telephone cables for transatlantic transmission.

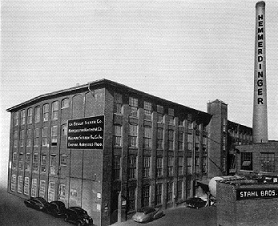

Henry named the newly acquired property in central Queens, Atlas Terminals. He moved his operations to a 300,000 square-foot space in buildings now designated 1, 2, 3, and 9. At that time, his company employed approximately 200 people and processed some 100 tons of fiber per day. It was a substantial operation equipped with 21 garnetting machines and a carbonizing range for degreasing rags.

Henry began renting out excess factory space that was not utilized by his own company.

In order to attract tenants, Henry built a garage on the property. At the time, trucks were a relatively “new technology” and were not particularly reliable. The garage ensured that even a truck that limped into Glendale from Brooklyn, Manhattan or as far away as Providence, R.I, could be repaired and put back on its way.

Before long, Henry was constructing new buildings on the site. Many were built under the direction of local resident Oscar Zeigelmeier, a master mason whose last name, in fact, translates in German to “supervisor of a group of bricklayers.”

“Some of the buildings were built when the local concrete manufacturers had ‘extra’ concrete,” explains Kate Hemmerdinger-Goodman, Henry’s great-granddaughter. “Henry would make the deal and direct the entire operation himself, pointing to an approximate square and commanding the men to ‘pour the floor.’ And that’s why, to this day, some of the Terminal’s buildings have rather ‘creative’ shapes.”

Henry Hemmerdinger died in 1946 at 66 years of age. He had expanded Atlas Terminals from four buildings to 31 with 786,000 square feet of space. He served as director of the Advertising Club of New York and of the American Club of Cuba — Cuba was one of his major markets for the garment scraps.

He was an active supporter of the Queens Children Shelter. Henry also found time to be a member of the Harmonie Club of New York, and a director and commodore of the Knickerbocker Yacht Club. Besides the business acumen which contributed to Henry’s highly personalized management style and rare commitment to his clients, he was known for his generosity to neighborhood children, this attribute was best exemplified while serving as an active director of Jamaica hospital.

Upon Henry’s death, his son Monroe took over management of the facility and continued to expand it. Monroe, the first member of the family to attend university, joined the family business in 1936 after graduating from Brown University. During World War II he served as an officer in the Navy, and lived with his bride, Carol Weil in Washington, D.C. Henry Dale was born there in 1944.

By 1949, Monroe had completed another enlargement of the Terminals. There were now 40 buildings comprising over 800,000 square feet of space, 5 miles of paved roads, and 8 miles of railroad track with their own switching engine to move the cars around. These railroad tracks were laid, because much of America’s goods were moved by rail before the advent of cargo jets and of the interstate highway system. The locomotive is currently situated along Cooper Avenue at the main entrance to the Terminals.

By the early 1950’s, Atlas Terminals was one of very few industrial parks within New York City. Atlas housed prestigious tenants such as Kraft, General Electric, New York Telephone and Westinghouse. At this time Monroe decided to sell off the rag business. He focused his energies on expanding his real estate holdings and built a career working with a wide range of properties, including industrial properties in Miami and New York and two Manhattan office towers.

After Monroe’s untimely death in 1962, at the age of 46, the company was run by non-family members until 1967, when Henry Dale Hemmerdinger began working at the Terminals. Dale’s first job in the family’s business was to construct a new building to house the growing company’s offices, replacing the farmhouse that dated back to before Dale’s grandfather’s 1922 purchase of the property.

In 1970, Dale became president of Atco Properties & Management, Inc., an acronym he created from “Atlas Terminals Corporation.”

In an effort to appeal to the shifting needs of many of Atlas’ manufacturing, warehousing, distribution and office tenants, the company opted to undertake a major renovation in 1986. Virtually all of the buildings’ exteriors were upgraded and weatherproofed, and new roofs were installed throughout. A new high-pressure boiler to provide heat was installed, and the train tracks that had fallen into disuse were paved over to allow wider roads so that the new 18-wheel delivery trucks could range throughout the facility. This became an imperative as manufacturing turned to warehousing, shipping and distribution companies, many of whom are the Terminals current tenants.

During this renovation the four-story “main” building that stood on the property in 1922 was completely reconstructed, a project that was honored by the Queens Chamber of Commerce in 1989.

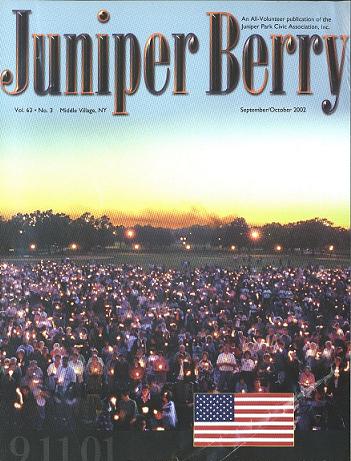

At the same time, the company continued to participate in community activities. For example, starting in the mid-1990s, Atco has played an active role in the Glendale Chamber of Commerce’s annual holiday festivities. The company also provides space annually to the Boy Scouts for storage and distribution of cookies, and planted and maintains the trees that line the streets surrounding the Terminals.

Nowadays, the 44-building, one-million square-foot Atlas Terminals property holds a mix of old and new tenants active in a variety of industries. Current tenants are not the blue chip companies that occupied the area in the 1950s, but are local businesses, many of which struggle to survive.

There are food importers; bakers; manufacturers of hospital furnishings, lighting fixtures, telephone calling cards, and picture frames; silk screeners and microfilm scanners; knitters; distribution facilities for candy, medical supplies, leather goods, sheet music, furniture, and school supplies; home-health care providers; and companies that sell pet food and coffee both wholesale and retail. Several office tenants, including the Community School Board and the Queens Symphony Orchestra, also occupy the property. Commitment to adaptive re-use has remained a constant, helping the Terminals succeed over the years. Henry used the site for his linen-waste management business; Monroe expanded the facility and added railroad tracks and paved roads for industrial use; Dale grew and diversified the park by changing it from purely industrial to mixed-use.

Now Dale’s children, Damon and Kate, have joined the business. They represent the fourth generation to take an active role in the Corporation, and are already leaving their own mark on Atlas Terminals.

“My grandfather purchased the Terminals,” explained Dale Hemmerdinger, “my father expanded it, I adapted it, and now my children are about to alter it. We’re not developers, but owners, five generations of New Yorkers committed to preserving our community. Buildings are only valuable because of what is done in them or who lives in them.”

“My sister and I are excited to continue to seek a dynamic relationship with the community,” added Damon Hemmerdinger. “When factory workers lived in the neighborhood, we depended on them to fill the jobs of our tenants whose businesses were mostly light manufacturing. Now that the community is more affluent and has leisure time, and now that manufacturing is less and less available for local jobs, we are making plans to adapt the site to suit the community’s current needs and circumstances. This project helps to ensure a role for our children, the next generation, to continue thinking of the heart of Queens as the heart of our family.”

Information about the upcoming plans for Atlas Terminals will be described in a forthcoming issue of The Juniper Berry.