In the last issue of the Juniper Berry, I provided some background about the dedication of a WWI monument consisting of live trees and a bronze plaque within Forest Park. The questions raised by the research: Where exactly were these trees and what happened to them? And secondly, whatever happened to the granite memorial with the bronze plaque? These were mysteries that the Woodhaven Cultural and Historical Society wanted to solve and our first stop was the local papers.

It was through the archives of local papers such as the Leader-Observer, the Brooklyn Eagle, and the Long Island Daily Press that we were able to piece together the story of how the Woodhaven Memorial Trees came to be, but none of them were very revealing as to their fate.

From the articles, we knew the trees were near the “Golf Clubhouse” which we know today as Oak Ridge, which houses the administration offices of Forest Park. But, not for nothing, Oak Ridge is surrounded by trees – that’s why they call it Forest Park! However, buried deep in one article was a description stating that the trees were “along the drive near the clubhouse.”

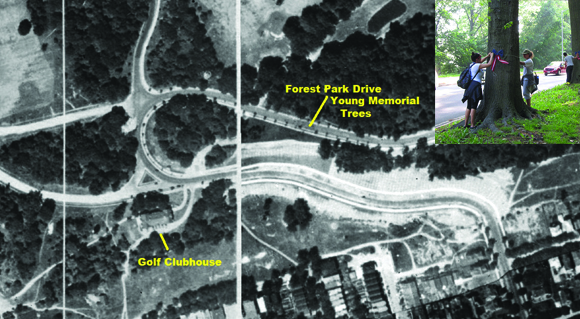

From there, we went to the NYCityMap website, a terrific resource that one can easily get lost in for hours. At this site, you can enter an address, or an entire Zip Code, and see aerial photographs of your community as far back as 1924.

If you look at the old Forest Park Golf Clubhouse in 1924, just a few years after the trees were planted, you will see a number of small trees, lined up along Forest Park Drive, starting from the entrance of the park, winding past Oak Ridge, and around towards the Seuffert Bandshell.

Counting just how many young trees were there is a bit difficult as there are larger ones blocking our view, but it looked to be around 50-60 trees, right in the ballpark. A call to the Forest Park Administration confirmed that the trees today along Forest Park Drive are, indeed, oak and roughly 100 years old.

So, we had found out what had happened to the trees – nothing. Other than the ones that had fallen victim to storms, many of the trees are still standing. But what about the granite tablet? Here we got lucky when we searched through an old scrapbook belonging to the American Legion and found a reference to the monument being moved from “Memorial Knoll” to the new American Legion building.

When American Legion Post 118 in Woodhaven was formed, it took up residence in an old building formerly owned by the Wyckoffs which sat on Woodhaven Boulevard. However, when Woodhaven Boulevard was widened in the late 1930s from one sleepy road to 10-lanes, many houses and sections of Woodhaven were demolished to make way. American Legion Post 118 was one of those buildings, and they moved to their newly built headquarters on the corner of 91st Street and 89th Avenue, where they still reside today.

And to this very day, sitting outside the building on its’ front lawn, is the granite monument with the brass plaque paid for with so many lives and two Tag Sales. Once they moved to their new headquarters, and had a nice front lawn, it made sense to move the monument closer to the neighborhood.

Throughout the 1940s and beyond, the parades marched through Woodhaven, stopping at Whiting Square and visiting the newer WW2 monument at Forest Parkway, before ending at Post 118’s headquarters, where they would erect a Garden of Remembrance around the monument; a yard full of white crosses, with the names of the departed on them. They still erect that Garden to this day, also paying tribute to the fallen in the subsequent wars as well as all of their members who have passed.

And so, over time, as the families grew old and died off or moved away and other ceremonies took over, the trees in Forest Park and their original purpose and meaning have been forgotten. Until today.

Today the trees still stand but the road that these trees sit upon, Forest Park Drive, is in dire need of repairs. The roadway is full of potholes and long overdue for paving; the sidewalks are cracked, poorly patched and in some areas, completely missing. It is far from being up to standards for a normal everyday road through a park, much less one with trees dedicated to those who sacrificed their lives for our country.

Late last year, the Woodhaven Cultural & Historical Society gave a presentation of its findings to American Legion Post 118 whose members were extremely interested in paying honor to the young soldiers that these trees were planted for. This year, Post 118 decorated those trees with patriotic bows for Memorial Day, reviving a tradition that lay dormant for over seven decades. “This is truly a remarkable discovery that will keep alive the memory of our local heroes who made the ultimate sacrifice during the first World War,” said New York City Council Member Eric Ulrich, Chair of the City Council Veterans Committee. “I was happy to work with the American Legion, the Woodhaven Cultural and Historical Society and the community on this project that has enhanced an already beautiful and historic park in Queens.”

“This is an exciting discovery, and I applaud American Legion Post 118 and the Woodhaven Cultural and Historical Society for reviving this tradition,” said Assemblyman Michael Miller, whose office sits not far from the Memorial Trees. “Given that it is exactly one-hundred years since the trees were planted, I think the interest surrounding the war’s centennial helped their efforts.”

The Woodhaven Cultural and Historical Society has a Research Study Group which is now working on filling in as much of the background of these soldiers as we can. Over time, we’ll tell the story of the young man from 96th Street who was, fittingly, an aspiring forester and writer who once was chosen to parade before King George and wrote letters to the Leader-Observer.

We’ll tell the story of the young man who was an entertainer, a singer and a dancer and a popular member of the Woodhaven Athletic Club, whose death according to one article “cast a shadow over the entire neighborhood.”

We’ll tell the story of the young man known as the King of Eastern Hurdlers who set a world’s record at Madison Square Garden the year before he died of gangrene from wounds received in battle.

These young men, and dozens more, are represented by a tree in our living, breathing memorial that sits, no longer forgotten, in Forest Park.