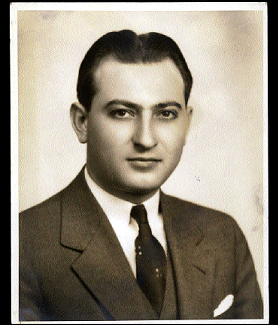

Measuring success in someone’s life is not always in easy task. But in the case of Frank Principe, who will be 90 years old on December 5, success can be measured in any number of ways. To Frank himself, success in life can be measured by- the devotion one has to one’s community. By that yardstick, Frank indeed has been a roaring, ebullient, resourceful, resounding success who has devoted and continues to devote his life to the place where he lives, Maspeth. Frank now is the chairman of Community Board 5, overseeing a body of 50 community leaders appointed to be the watchdogs of their community. Frank is a vigilant watchdog, but his impact on the community he serves goes way beyond that. He can be considered one of its founding members, playing key roles in the community’s development. And he continued to nourish it with his energy and vision as the years went by.

Given all that, Frank is just an interesting guy whose life has been colorful, intersecting as it did with several personages of history including Benito Mussolini, Robert Moses, Fiorello LaGuardia, Pope Leo, and others. Businessman, builder, father, community leader, raconteur, visionary, and politician in his own right, Principe deserves thanks and a tribute. His nearly 90 years be chronicled here in this issue and subsequent issues as his birthday approaches. This first installment will cover his early years including his youth in Brooklyn, memories of his father, and meeting Benito Mussolini. Other segments will deal with the life he started in Maspeth, his effort to build the “Ridgewood Plateau” and Maurice Park, the start of his own concrete company and his fight to keep it out of the hands of organized crime, his contribution to the war effort, and various community projects he took on over the years to make his community the best place for families and businesses alike. This installment was based on stories told to Paul Toomey over the course of a four hour discussion with Principe at his home in Maspeth. What is clear from the session is that Principe, at nearly 90, is just as sharp, witty and charming as ever. He wants to live past 100. We hope to do his life justice. Happy Birthday, Frank. Here, goes.

For the first time in his life, 17-year-old Frank Principe, a normally happy-go-lucky youngster who loved baseball, scouting and building his own radio was in a funk. His father Louis, who was emerging as an important businessman in Brooklyn, was planning another trip to Europe. As in the many times past, Louis would not be taking his son. Frank, who had never even left Brooklyn, could only dream of visiting the places his father had already been. And dream he did.

Whenever his father was away on business, representing the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce as its president, Frank would miss him terribly. he loved his father. But, more than that, Frank idolized him. To Frank, his father was bigger than life and, to this day, he remains a role model for him and his greatest influence. Tall and robust, Louis had the personality of a Grand Duke and the bearing of a general. He would later rise to become a city commissioner and a man with considerable political influence.

Louis had come to the United States at the age of 19 from a small town in Italy near Abruzzi seeking the good life. The roads, he knew, were not, all paved with gold, but at least they were paved. The beckoning land offered, at the very least, the chance to make something of himself. His own country was poor and did not seem to offer a young, ambitious man many opportunities.

Coming to America with only a third grade education, $1.75 in his porket, and no knowledge of the English language, Louis Principe seemed totally unprepared to face the dangers and challenges of the New World. In fact, shortly after he landed if 1903 and settled into the burgeoning Italian community of East New York, Brooklyn, Louis took a job in a bakery and promptly managed to cut off his left forefinger in a dough mixing machine.

But Louis remained undaunted by his stroke of bad luck and Frank will say of his father that he was a pioneer with a pioneer’s spirit. Affable. good-natured and honest, Louis lived in a rooming house in back of the bakery in which he worked with several other Italian immigrants. After the accident, he decided against a career, in baking and turned to the only other thing a young man with a strong back and no education could do: bricklaying and a chance to get in on the ground floor, so to speak, of the construction trade.

While he sought out work, he received aid from a local Italian organization that looked after newly-arrived immigrants, the Amerigo Vespucci Society of Mutual Help. With his outgoing personality, good humor and intelligence. Louis became a popular member and eventually became its president. Frank recalls an early memory of his father’s bigger-than-life personna: his father, marching in a parade leading the group of men from the society. but what he remembers most clearty is that his father was waving at the passing crowd while riding on a huge white horse, he never forgot that, Frank says. During the early 1900s, East New York was a bustling place of business where the elevated train line from Manhattan’s Mulberry Street came into a junction at Fulton Street. The city was in the process of installing sewers and grates, and part of that project was the 1aying of brick to secure them into the street. Louis joined a work crew that laid the bricks.

A hard-worker, Louis caught the eye of the foreman who proposed that Louis organize his own work crew of Italian immigrants. During the daily shape-ups,any mason worth his salt would carry his own equipment over his shoulder: usually a trowel, a level or a shovel. To find work. the Italian masons would try to compete for work with the German bricklayers who were in America longer and controlled the market. The Germans also worked in the more elegant neighborhood on the other side of Highland Park, Ridgewood.

Frank remembers one time accompanying his father on a job to Troutman Street. He was only eight and worked as an errand boy. The foreman who had arranged the job didn’t tell his workers that the Germans might not like their crew working in their territory. So, when the Italian workmen arrived at the job, they were met by four burly Germans sent to scare the Italians away or rough them up it they didn’t leave.

After a few tense moments, Frank remembers his father grabbing a shovel and putting it to throat of one of the goons. The other, man in the work group, seeing the danger, raised the pointy ends of their trowels ready to defend themselves from a possible attack. But with Louis’s bold and swift action, it was the Italians who won that day Frank recalls, and without, bloodshed. The Germans backed off and the Italians went back to work. But it was a lesson to young Frank about his father’s determination, a lesson he would carry with him the rest or his life,

Louis became one of the most active bricklayers in Ridgewood, breaking the German monopoly in the area, Frank says. But times were not always good and finding work could be a struggle. It was during one of these slow periods, about 1907, when his father was out looking for work and he became smitten with the pretty young woman who worked inside a small grocery store an Stone and Rockaway avenues. That woman, Virginia, was to become Frank’s mother.

At Five feet two inches tall, Virginia had also come from Italy, from a small town outside of Naples. Like Louis, she had travelled alone at the age of 19 to the New World. But, where Louis was tall, six feet one inch mind over 200 pounds, Virginia was short, and where Louis could be Loud and boisterous, Virginia was “Wet mind somewhat, shy. “They were like Mutt and Jeff,” Frank says.

During their outings on the many Sunday afternoons they walked hand- in-hand around the Highland Park Reservoir, where couples picnicked and necked on “Lover’s Lane,” the two developed a bond. They married later that year and moved to an apartment on Ralph Avenue.

After miscarrying her first child, Virginia then gave birth on December 5, 1909 to Francesco Principe, who was named after Louis’s Father.

By the time Frank was 10, the Principes bid farewell to East New York and moved to what was considered to be a classier section of Brooklyn, Kensington, or what was generally known as greater Flatbush. Louis, now an accomplished bricklayer, had taken a house in payment for a job. The house was located on Webster Avenue near the McDonald Avenue elevated line. It was still a rural neighborhood with farms and lots mixed in with grand, two-story wooden homes. Those homes were filled with Irish, Germans, Norwegians, Swedes and other “American” families. The Principes were among the first Italians to move in and, at the time, weren’t welcomed, Frank remembers.

All in all, Frank has fond memories growing up here, despite the ethnic rivalry of the day. Small in size (he took after his mother) and outnumbered, Frank was picked on by a gang of neighborhood boys. That was until his innate scrappiness took over. One day, Frank flashed a knife to fend off a bully. Then, in an attempt to stop the the bullying, Frank singled out the leader of the gang in a fist fight and beat him. He was accepted after that.

At home, Frank was “buried in Italian culture” because his house became filled with relatives arriving from Italy; all 13 of them including cousins, aunts and uncles. The household also included his brother Louis Edward (now deceased), who was born in 1917, and his sister Marie, born in 1920, who now lives in Maspeth.

At dinner, the now American Principes would joke with their immigrant relatives about which way of life was better; the American or the Italian. Frank remembers making fun of the pantaloons his aunts wore as undergarments, something no modern American woman would be caught dead in.

During this time, Louis reigned at the head of the table, the family patriarch and breadwinner, who set the rules and lead the family discussions. As was his custom, he would often invite various dignitaries to their home for a home-cooked Italian meal. Frank remembers seeing a statue of a WWI general erected in front of a nearby armory and then seeing the general himself right in his own dining room after his father invited him home for dinner one night. Frank was a little starstruck at first, but it wore off.

Frank has other memories too; his unmarried aunts beading dresses for a garment district employer; of playing the outfield for his sandlot baseball team; riding his own pony on a western saddle and caring for the animal in the barn behind the house; of having to attend Methodist Sunday school so he could play on the Methodist basketball team; and being confirmed at the St. Rose of Lima Roman Catholic Church, where his family worshipped devoutly.

He also remembers getting hit in the behind with a BB from an irate neighbor’s gun after he was caught stealing tomatoes from his yard; tinkering with an old ham radio he bought with the savings from his $2 a week job as a butcher shop delivery boy; his listening transfixed to military signals sent from the Brooklyn Navy Yard in Williamsburg and of proudly perfecting his radio so he could send signals as far away as Atlanta, Georgia; and going to school, first at P.S. 134 on 18th Avenue and then at the Manual Training High School in Park Slope, which later became John Jay High School.

School was important to Frank mainly because his father impressed upon him that an education was necessary if he was to rise above the life of an ordinary working man. Louis even tried to set an example to his children by engaging in his own form of education; reading the Brooklyn Eagle newspaper every day. But there were other lessons Frank learned from his father that he took to heart.

One of those lessons occurred on the day when Louis told Frank to get behind a wheelbarrow full of bricks and lift it. “If you don’t go to high school, you’ll wind up pushing this wheelbarrow,” he told his son. Frank was instantly convinced. “Pop, I like studying,” he responded. “If you like studying, then make sure you get on the honor roll,” Louis needled.

When his father began taking trips to Europe on behalf of the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce, Frank fell into a depression and complained that he wanted to go with him. Louis said he’d make a deal with his son. “What is the highest award you can get in your high school,” his father asked. Frank said, “Why, the Arista medal,” he said. “Well, you get the medal and I’ll book you in June for Europe,” Louis said.

Frank was determined after that. He worked hard in getting good grades and in his extracurricular activities, which included managing the football team and being a leader in the school’s student finances. In June, after winning the medal, Frank went back to his father and told him. “It’s pay up time, pop.” Louis honored his promise.

After graduation, Frank sailed alone on the S.S. Roosevelt to Bremer Haven, Germany, where he was to head to Berlin to meet his father. It was the first time he was away from home and he was lonely. But, while on the ship, he met Jackie Blumberg, a friend he’d played baseball with who was en route to the Holy Land with his rabbi and some others from his synagogue. It made the trip go faster and easier, he said.

As the ship headed across the Atlantic, Frank planned to fly to Berlin once he reached port. But, as the ship was pulling into the harbor, Frank remembers hearing a whistle and a tug boat sailing toward the ship. Frank looked out over the railing and saw the tug steaming toward them with his father waving at him from the bow. He was happy to see his father, but disappointed at the same time because his plan to fly to Berlin was now scuttled.

Frank then toured Europe with his father, meeting various dignitaries in Germany, Switzerland and Italy. In fact, his father had gotten an invitation from the Ducha himself, Benito Mussolini, to come for a chat. Mussolini, who was in the fifth year of his reign in Italy, wanted to know what the Italians in Brooklyn were thinking about the progress he was making.

When Frank and Louis arrived at Mussolini’s office, Frank was impressed with its size and grandeur. “It was like the ballroom at the Waldorf,” Frank said. “We walked in and saw this head jutting up from behind a desk down at the end of this long corridor. Mussolini liked his office like that so he could see who was coming to see him and he could size them up. It was magnificent.”

After shaking hands with Mussolini, the two Brooklynites sat down. Louis said that the Italians in Brooklyn were impressed with Mussolini’s efforts to make the trains run on time and the war he was waging against the Black Hand, which controlled much of the Italian economy.

“Then, he turned to me and asked me if I was enjoying my time in Italy,” Frank said. “I was nervous and didn’t know what to say. I told him I thought everything was great because there was a soldier on a train who gave me a basket of food for lunch. He laughed.”

Frank said he liked Mussolini. “He was a Guiliani-type of guy. You know, for the people,” Frank said. “That was until he fell in with that bum Hitler and changed his whole life. He treated me nice.”

After leaving Mussolini, Frank and Louis went to the Vatican and kissed the ring of Pope Leo, another “great” experience for an 18 year old, Frank recalls. “And it was all because I won Arista,” he said.

Those were heady days, but in September, Frank was off to college, Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. Frank is modest when he describes the achievement of getting in to such an Ivy League institution. He simply says, “They accepted me.” He picked Cornell because he liked the countrified pictures of the campus he saw in a catalog from high school. “I had nobody to guide me,” he said.

When he got to Ithaca, he felt much like his father must have felt as a wide-eyed immigrant coming to the shores of a new land. Frank said he didn’t even realize until arriving in the small college town that he would need a place to stay and that he hadn’t made any arrangements before hand.

So, with suitcase in hand, Frank was directed to a rooming house in town, where, purely by coincidence, he shared a room with someone from Bensonhurst, Gene Maiorana, a brilliant student who was also a 100 yard dash champion in high school and an accomplished base stealer on Cornell’s baseball team. Frank is still friends with Gene today, playing golf with him regularly.

At Cornell, Frank studied civil engineering, but says he won no honors and, more discouraging, did not make any varsity sports teams, although he played intramural sports. Frank graduated in 1931, with the expectation of starting his new career. Unfortunately, the country was in a depression and Frank says there were no jobs to be had for a new graduate, Cornell or not.

What then was he going to do with his life? How was he going to make a living and impress his father with his own achievements? How was he going to make a name for himself if he couldn’t find a job? These were some of the questions Frank wrestled with as he held his diploma and tassle in hand. Frank would answer those questions and he would turn his eyes forever after to a new area outside his native Brooklyn that was just in the process of developing Maspeth.