Close your eyes, let your mind’s eye travel back one hundred seventy-five years and try to envision our current city in 1845. James Polk had just been inaugurated president of the United States which at that time consisted of 27 entities with the recent addition of Florida. Texas would follow within the year bringing that number to 28 and along with it the Mexican-American war. A local Middle Village man, James Harper, who had become a success in the publishing industry, was finalizing his term as mayor of New York City, an island located between the North (Hudson) and East rivers. The summer of that year brought a devastating fire to the city turning about 350 buildings and residences to ash and taking more than a score of lives. Most travel was done by horse and carriage, boat or foot. Railroads were in their infancy.

The growth of the city was on a never ending surge northward on the isle and leaders recognized that their Gotham had to evolve in order to become a world class center of commerce, culture and education.

While the northern county of Westchester was farms and estates of the wealthy, the closer eastern counties of Kings and Queens consisted of small towns and farms and farms and more farms that fed the metropolis to the west. About this time the city leaders grew concerned about a mounting and never ending question, what to do with the dead? Most cemeteries were on ancient church grounds or on land that predecessors thought would never be occupied.

Wrong.

Political leaders lobbied Albany and in 1847 the Rural Cemetery Act was passed allowing for commercial cemeteries.

New York City banned new graveyards in 1852 which followed the City of Brooklyn’s decree in 1849. The land rush immediately commenced and our sleepy, lush, beautiful and bucolic neighborhood populated mostly by those of British heritage took a giant leap onto the path of transformation.

The Archdiocese of New York bought several farms in Maspeth and Woodside and formed Calvary Cemetery. James Maurice, a politician from a local family, and others joined to form Mount Olivet Cemetery. In 1852 the Rev. F. W. Geissenhainer and cohorts founded Lutheran Cemetery as a non-sectarian burial ground. The cemetery’s beginnings originated from several small family farms, including land of the previously mentioned Harper family, and then St. Matthew’s Church and churchyard. Starting in the late 1870’s the Diocese of Brooklyn acquired several farms farther east along the Williamsburg and Jamaica Turnpike, now Metropolitan Avenue, that in 1879 became St. John Cemetery.

With cemeteries acquiring hundreds of acres of prime farm land, agriculture slowly faded and the business of Death became the prominent industry in the community. Florists, hotels, saloons and masons took up in the area.

Farmers became florists. Large family homes became hotels and saloons, barns became livery stables and stone masons attempted to produce grave markers. The masons soon realized that there was a dearth of artisans available to cut stone for the many needed memorials; it was a discipline that demanded experienced personnel which was lacking in the immediate area.

Word went out that opportunities for stonecutters were in high demand in Queens, an area hard by New York City. The news soon spread to Europe and broad-backed men from Germany, Alsace, Austria, Bavaria and Italy hauling mallets, chisels, measuring rules, squares and calipers appeared.

Stone masons soon acknowledged that the newly arrived immigrants possessed a skill nowhere near that of theirs and they soon became entrepreneurs, Monument Men. They hired the new arrivals and put them to work carving small to massive marble grave ornaments to the deceased.

However the stonecutters were not at all ignorant. They quickly realized that most of the consumers of their art were immigrants like themselves who spoke a language the same or similar to their own native tongue. They didn’t need mason employers; they could procure slabs of stone and start their own businesses or become freelance carvers and use the masons as their agents. Eventually they too became Monument Men.

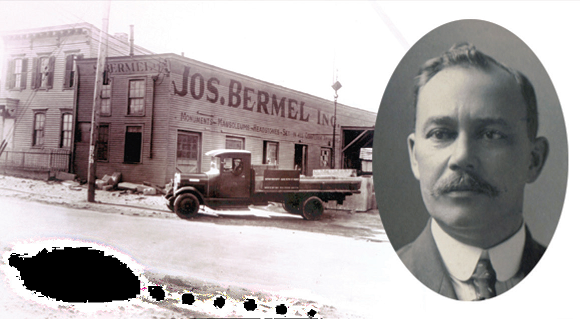

Eventually names like Sutter, Bermel, Homeyer, Lux, Lang, Meckler, Paulus, Braun, Auricchio, Riley, Seiz, Bleser, Gute and others appeared on storefronts and signs above their establishments featuring their trade and abilities.

These advertisements lured the public into their web of mourning. Quite a few businessmen also applied copper plaques with their names and location attached to monuments and stones. Some even carved their names into the bases of the gravestones. Many of these are easily viewed in All Faiths and St. John cemeteries. Others from outside the immediate area also plied their trade; names like Boettcher, Baxter and Ferdinand Prochazka of Madison

Avenue, New York City, appeared on monuments. By 1880 Lutheran cemetery had more burials per annum than any other non-sectarian cemetery in the nation. The Monument Men were quite busy.

In time literal cracks began to materialize. Marble, being a fairly soft stone, began to deteriorate. Monuments, once gorgeous, lost their drama. Names vanished. Statues of angels fell to the ground losing their wings and little could be done to save this artwork. Some of the surviving gravestones were made from sandstone which resembled many of the markers found in pre-colonial and colonial family and church burial grounds. Cemeteries noticed and instituted new rules. Future monuments must be made from granite; a much harder stone that would not decay due to weathering became the rule. It also meant an alteration in the abilities of stonecutters.

No longer were sculptors experienced in turning marble blocks into statues needed. The business became industrialized. Granite could be quarried in Vermont, Massachusetts and Maine and turned on site into the more modern grave markers we see today.

In the late 19th century granite became king of the necropolis. The Rock of Ages era had arrived. No longer did the Monument Men have to maintain large yards of stone. A showroom of precut granite markers could be assembled near the cemeteries or customers could pick and choose from a catalog of stones that would fit their assumed stature in society. One could even purchase a headstone from a Sears Roebuck catalog. Corporations assured that their product would last for as long as visitors chose to remember their beloved’s graves. However there still had to be certain additions carved into the stones. Inscribing the names, years of birth and death of the deceased and those who shared the grave and headstone had to be performed. Stonecutters were still needed for that chore, meaning very skilled professionals because even a slight mistake could mean a hefty financial setback for a Monument Man. In time sandblasting replaced many a mallet and chisel. With this technology names and dates easily appeared and families could even have a photo etched onto a stone so all could remember the visage of the deceased loved one.

Those who have resided in this town for many years might remember the distinct shops that dotted the perimeter of our cemeteries. Auricchio on the corner of Metropolitan Avenue and 80th street, Homeyer on Metropolitan across from Mount Olivet Crescent, Lux on the corner of Eliot Avenue and Mount Olivet, Bermel on the corner of Metropolitan and 69th street and later on 80th street and Metropolitan. Across 69th street was Frank T. Lang whose famous building still graces that corner and a block farther down the avenue was Sutter on the corner of Metropolitan and 70th Street which used to be named Sutter Avenue and before that Contrell street.

Take a leisurely stroll through one of our tranquil cemeteries and view the lay of the land as it has been for eons and then marvel at the artful carving left to us by the local Monument Men and their Stonecutters.