Frank Banoff, a lifelong resident of Maspeth, took a job with Catholic Charities because he wanted to help seniors. He delivered for Meals on Wheels, but when climbing stairs became too difficult, he started driving the bus that shuttles seniors to and from the center. He didn’t just drive them around, he developed friendships with them, and when they became ill he would visit them in the hospital and bring them cookies that his wife had baked.

One day while Frank was picking up his passengers, he struck up a conversation with a gentleman by the name of Tony Vaccaro. The topic of photography came up. Frank had been an avid photographer for more than 40 years and even developed his own photos in his darkroom.

Tony is a retired photo-journalist and fashion photographer, and for more than 70 years, has also developed his own photos in his darkroom. Tony has no intention of going digital. “Film vs. digital” is a hot topic amongst photographers.

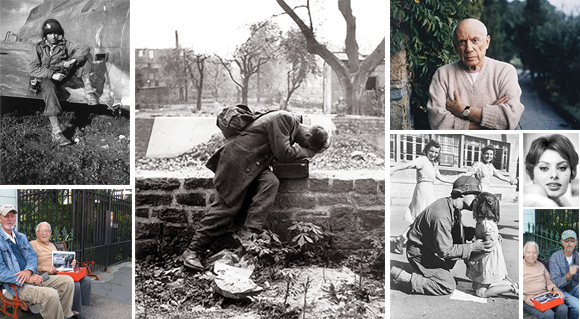

Frank and I were invited to Tony’s home and we were amazed by all the photos of celebrities that he took while working for magazines in Europe and the USA. Some date back as far as the 1950s. His photos take up every inch of wall space in his apartment, and behind every photo, Tony has a story that he can recall with great clarity. Over the years, Frank and I have met with Tony many times and we have always found him to be a gracious man and very generous with his time. His life is an amazing story that we are sure others will find interesting, too.

Michelantonio Celestino Onifrio Vaccaro was born in 1922 in western Pennsylvania. His parents were Italian immigrants. They also had two daughters: one younger and one older than Tony. When he was three, his family returned to Italy to visit their relatives. While there, his mother became ill with an infection and died. His father left his three young children with his brother’s family and went back to the US to work. He returned to Italy after two years, and died in a tragic accident when he was thrown off a mule and impaled on a tree. Tony and his sisters remained in Italy and were raised by their aunt and uncle. As a young boy, he loved the rural countryside and loved to walk to town. His uncle had a barbershop and Tony liked to look at the magazines and newspapers, especially the photographs. Before long, he had gotten his first camera, which led him to his lifelong passion.

There was rising fascism in Italy in the 1930s and Tony remembers hearing Mussolini’s speeches. They scared him. To avoid the threat of being drafted into the Italian army, the kids were sent back to the US to live with relatives in New Rochelle, NY, where Tony attended high school. It was at school that Tony met a teacher who encouraged him to join the camera club and follow his dream of being a photo-journalist. When he graduated in 1943, he was drafted into the Army and, after training in Mississippi, he found himself on a troop transport ship heading to England where the Allies were preparing for the greatest offensive of WWII – D Day. Tony brought along his camera – an Argus 35mm – that he worked all summer to buy. He was given permission by his commander to take photos that could possibly be made into a book about their unit, the 83rd Infantry Division.

His safety and the safety of his fellow troops always came first, photos second. At Normandy, troops were loaded onto landing crafts and headed for the beach. They were met with heavy German resistance from well established defenses and from aircraft dropping bombs which took a heavy toll. Many troops never made it past the beach head. The 83rd Infantry made their way through France, Luxembourg and Brussels pushing the Germans back and capturing many to the delight of the liberated people who hugged and kissed the American soldiers.

Tony was a scout that would go out ahead and question local people about German positions. At night, he would develop his photos using his buddies’ helmets to hold the chemicals. He would hang the negatives on a tree branch to dry. These were very primitive conditions to work in and his buddies weren’t happy because their helmets smelled of chemicals, but it worked.

It was on the Belgian/German border that the Americans met a German force that was well entrenched in the Hurtgen Forest. This battle became the largest battle on German soil in the war and also the bloodiest battle of the war for both sides. The battle lasted from September 19 to December 16, 1944 and is considered the longest battle in US Army history. This battle preceded the Battle of the Bulge, which was the last great offensive by Germany, but failed at stopping the advancing American and British troops. The 83rd Division was one of the first American troops to enter Germany and Tony says it was sad to fight young boys and old men because that is what the Germans had resorted to. He saw so much destruction of once-beautiful cities and it saddened him greatly. As a young man, Tony considered himself to be a pacifist and was against war but he believes Hitler and the Nazis had to be stopped and it couldn’t happen without America’s involvement. During the war, Tony took 8,000 photos. One of his photos is of an American soldier lying dead face down in the snow; he calls it “White Death.” It is of his friend Pvt. George Tannenbaum from Brooklyn. As the Americans lay wounded in the field they were shot in the head by a German officer. This was a very difficult photo for him and he cried while taking it. Fifty years later, an important German magazine’s readers voted this the most important photo of the 20th century.

Another photo is of a small child kissing a GI while women are dancing around them and it is considered one of the best photos of the war; he calls it “Kiss of Liberation”. When the Germans surrendered in May 1945, there was talk of sending his outfit to the Pacific to fight the Japanese, but the war ended in August 1945 and he was soon discharged from the Army and sent back to the States.

The State Department was looking for a photographer to travel around Europe to photograph the destruction as well as the rebuilding of these countries. Tony was interviewed and got the job. He was given a Jeep and plenty of film and he documented what he saw. His photos capture people trying to pull their lives together amid all the destruction. Many of his photos are of the poor, the wounded and the children left without fathers. They truly capture the horrors of war. Many of his photos also capture the beauty of life and a hope that things will get better. For five years, he took many thousands of photos, but sadly, 4,000 of his negatives were lost in a flood in Spain.

He has published photobooks covering France 1944-1947, Italy 1945-1950 and Germany 1944-1949. He also provided photos for the book “Across the Elbe River Thunderbolt Division”- the story of the 83rd Infantry.

After returning to the States in 1950, Tony became a foreign correspondent for Life, Look, Venture, Time and Flair magazines. He traveled all over the world photographing many of the important people of the day in the arts, politics and science. On his assignments he met Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dali, Egypt’s President Nassar, Greta Garbo, Senator John Kennedy and an 18-year old Sophia Loren whom he considers his friend. He believes Frank Lloyd Wright was one of the smartest people he ever met. His 1957 visit with him at his Wisconsin home became a book about the man and the buildings he created all over the country including the Guggenheim Museum in NYC.

One of his assignments was to photograph the artist, Georgia O’ Keefe, for Life magazine at her New Mexico home and studio. She wasn’t happy to see Tony; she wanted a photographer she knew instead. For a few days she ignored Tony until she learned that he could cook authentic Italian food. She then opened up to him and he got some great photos. A few years ago, the Georgia O’ Keefe Museum in Santa Fe bought all of those photos. During his years working as a photo-journalist and fashion photographer, he had a penthouse apartment and studio on Central Park West and knew many of the artists, writers and painters in Greenwich Village, including Jackson Pollack and Willem de Kooning. He recently donated his photos of Pollack to the Jackson-Pollack Museum in the Hamptons on Long Island.

In the early 1970s, he, his wife and two sons bought a small house in Long Island City because he said it reminded him of a part of Paris he liked near the water. He has seen his neighborhood change from small homes mixed with manufacturing to luxury high rises sprouting up all over near the water and upscale restaurants along Vernon Blvd. He has enjoyed some recognition from newspapers and is a local celebrity. The owner of the restaurant/café, Manducatis Rustica, comes from one of the bombed out cities Tony photographed in Italy. She has purchased many of his photos and has created the “Tony Vaccaro Room” in the restaurant.

Tony made many trips back to Europe where he has been honored for both his military service and for his photos. Just last fall, universities in France and Italy made him an honorary professor. They sent him a ticket for the Queen Elizabeth 2 and when he arrived, he was met by a former Prime Minister of France that he knew as well as the press. He is more well-known and honored in Europe than the US. Frank and I hope to change that, as we feel he is an American treasure.

At 92 years of age Tony shows no signs of slowing down. June 4, 2014 was the 70th anniversary of D-Day, and Tony returned to Normandy where thousands of people and world leaders including President Obama honored the sacrifice so many made. He soon plans to embark on a 4-5 month lecture tour. He continues to hope that mankind will one day live in peace because war is such a waste of humanity. His photos tell his story and as long as people want to hear it he will tell it.

There are many websites about Tony and videos about him on You Tube. Some of his books are also available on the internet. He has also published a series of children’s books that are a delight.

Before he left for Normandy, Frank and I did meet with Tony at a small café near his home. When we got there, he was meeting with some of his friends from Europe, including two men who would drive him around France. Tony bought drinks for his guests and then excused himself so the three of us could walk to his home where we would talk about this story we were writing about him. While in his home, he received a phone call from President Obama’s personal secretary about a possible meeting with the President at the D-Day ceremonies.

How a man at his age can handle all that he does amazes me. I’m almost thirty years younger than he is and I get exhausted thinking about it. Thankfully, Tony said he liked the article and told us a few more stories that will be printed in a future issue.