The area of Newtown established as “Laurel Hill” in the 19th Century was comprised of 2 large hilltop farms – one owned by the Rapelye family and the other by the Alsops. The building that became known as the Alsop farmhouse dated back to 1651 and was purchased by Thomas Wandell in 1659, who, upon his death in 1691, transferred it and an adjacent 115-acres to his nephew Richard Alsop. As for the Rapelye property, it had been owned and farmed by Edward Waters, with Jacob Rapelye purchasing it in 1852. Jacob proceeded to build a mansion on the property at the top of the hill that existed along today’s 55th Drive between 44th and 46th Streets.

The bridge, the train and the road

The Penny Bridge, first built in 1836, was one of the few Newtown Creek crossings available at the time. It cost a penny toll to cross it, hence the name. The Flushing Railroad was built along the banks of the Creek and opened a station at Penny Bridge in 1854. The line was subsequently purchased by the South Side Railroad in 1869 and the Long Island Railroad in 1874. The East River Tunnels carrying the LIRR to Manhattan were not in service until 1910, so prior to then, the rail line was as valuable to ferry passengers crossing over to Manhattan from Hunters Point as it was to merchants shipping freight out to Long Island. Up until 1998, passenger trains made rush hour stops at Penny Bridge. In the late 1800s, many pedestrians using the tracks as a walking path were killed by trains, prompting the construction of Review Avenue/56th Road. Laurel Hill Blvd (alternately known as “The Newtown Turnpike and Shell Road”) was constructed in 1840 from crushed oyster shells and ran between the Penny Bridge and Broadway in Elmhurst. Today, its route may be traced by following the section still named Laurel Hill Blvd, the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, and 45th Avenue. The modern-day Laurel Hill Blvd acts as the BQE’s service road, although it becomes its own path at its 67th Street terminus in Woodside.

Calvary Cemetery established

The Alsops sold most of their farm to the Trustees of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in 1845 which allowed the Catholic church to expand on its original purchase of 71 acres of land from John McMenoy and John McNolte. The church was looking for additional space to bury their deceased congregants, as their Manhattan graveyard was rapidly growing short on space. The first burial in Old Calvary Cemetery was recorded in 1848, shortly after passage of the Rural Cemetery Act of 1847, which allowed for the establishment of commercial cemeteries in NY State. The Alsop Family Burial Ground, containing gravestones dating from 1718 – 1881, continues to be maintained within Old Calvary Cemetery, near what is now its “back entrance” off Laurel Hill Blvd, but the family’s home was demolished in 1880.

The hamlet grows

The farm behind the Rapelye house was sold for real estate development in the 1880s and the land was subdivided into residential lots, with Jacob’s son August continuing to live in the old mansion until 1890. The area seemed ideal at the time for both blue-collar living and working as it served as somewhat of a transportation hub near business that supported the cemetery as well as burgeoning industry along Newtown Creek. Small frame houses started dotting the landscape, and by the turn of the century, there were enough residents to support an Episcopal chapel named St. Mary’s (first organized in 1888); its flock was tended to by the rector of St. Saviour’s Church in nearby Maspeth. One small section of Laurel Hill was referred to as “Berlinville” as many of the inhabitants were German immigrants, but that name fell out of favor after a collision between two trains along its curved LIRR track resulted in the deaths of 16 people and serious injuries to 40 others. The 1893 incident was dubbed the “Berlinville Disaster,” and quickly became something with which the community did not want to be associated.

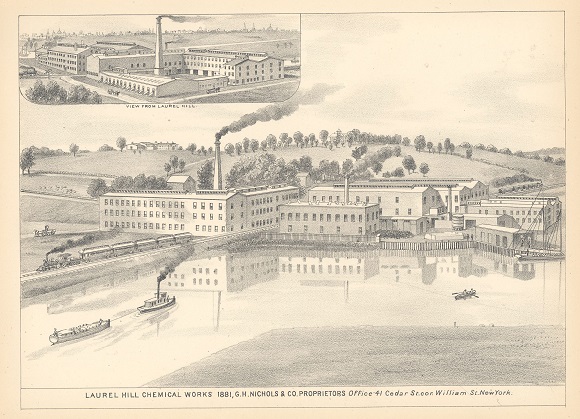

The rapid proliferation of industry along the banks of Newtown Creek served to discourage widespread residential development. Some of the main polluters included F. Haberman’s National Enameling and Stamping Company, which had their own LIRR stop near 49th Street, and Nichols Chemical Company, which experienced a spectacular fire in 1903. Phelps-Dodge was established in the vicinity in 1920. In the 1950s, Robert Moses’ highway plans doomed swaths of western and northern Laurel Hill to make way for the BQE-LIE interchange and the Kosciuszko Bridge (which replaced the Penny Bridge). St. Mary’s was, along with several homes and businesses, condemned and demolished, and parts of the street grid were permanently wiped off the map. The 1961 Zoning Resolution cemented Laurel Hill as a manufacturing town, declaring that no new housing could be constructed there moving forward.

Former residents remember

Street signs were posted on buildings decades ago instead of on poles. One quaint corner home existed up until around 2010, still sporting a pair of signs labelled “Clifton Avenue” and “Waters Avenue” along the top of its open porch. Today those streets are 46th Street and 54th Road, respectively. The last owner’s daughter, upon seeing the house featured on a blog post by Forgotten-NY’s Kevin Walsh, remarked on April 11, 2015, “It brought tears to my eyes to see the home where I grew up, since this home belonged to my Mom who passed away five years ago yesterday. It was hard to let the house go but one of the last things I did was take those signs off. Not sure why I kept them but could not part with them, pieces of my childhood.”

Another former resident of the area had written to FNY years ago to explain how he used to live in the only large apartment building in Laurel Hill, which was demolished to make way for the LIE. He described how, as a boy growing up in the 1930s, he and his friends hunted rabbits in Calvary Cemetery. “There were so many rabbits! Rabbits were absolutely everywhere,” he recalled.

Last trace of a name

Today, Laurel Hill is mostly developed with warehouses and factories, with very few houses mixed in, and is generally considered part of western Maspeth. Several homes that had survived were condemned in recent years to make way for the new Kosciuszko Bridge. The only trace of the name “Laurel Hill” left, aside from Laurel Hill Blvd, is inscribed on a flagpole in a park triangle along 48th Street, just south of the LIE. The monument reads, “Erected by the citizens of Laurel Hill in memory of those who died in the World War.” The inscription appears to have been lengthened later, adding World War II, Korean and Vietnam veterans to the honor roll.

The Encyclopedia of New York City describes the boundaries of Laurel Hill as follows: “It’s hemmed in by Calvary Cemetery/Brooklyn Queens Expressway to the west, the Long Island Rail Road to the south, the Long Island Expressway to the north, and pedal-to-the metal 58th Street, a main truck route, to its east.” That description is not very exciting, but its unimpressive sounding geography greatly contributed to its fascinating evolution.