Part II: The Triangle Fire and the Transformation of America

New York City, Gotham, has brought America many, many things. Our city is the city of immigrants, Wall Street, the media, high and low culture, and countless other things. In 1911, out of tragedy, New York City brought liberalism to America.

Now, liberalism has a bad name today in many quarters—judging from voting patterns in the Middle Village area we are a conservative lot.

But the liberalism I want to speak of is not the liberalism of the 1960s. It is a more universal liberalism that transcends the label itself. How liberalism was born of tragedy is an important historical lesson.

New York City witnessed a pandemic of labor unrest, overty, poor working conditions, and little public health. Our industries were chaotic and primitive. One industry defined New York City, the garment industry. One has just to think of the garment industry and the images of sweatshops jumps to mind. We think of sweatshops because they were so much a part of the industry it is impossible to think of clothing production without them, especially in the early 1900s.

NYC’s garment district was the site of thousands of small shops, most located in tenements, employing thousands of immigrant workers in substandard condition and low pay. The industry had, in essence, two sectors. The first was a modern factory production system that employed hundreds of workers in one building and through scale of production and efficiency eked out a profit.These shops were the minority.

The second, the so-called “moths of Division Street,”were the norm. These shops made a profit by sweating labor. They took contracts from “jobbers,” or middle men, to produce goods and were paid by the piece. In turn, they hired workers and paid them by the piece. The difference between their piece rate and what they paid was their profit.The cut-throat competition created a race to the bottom as the piece rates continually fell. Larger shops felt the competition and lowered their rates. Workers felt the squeeze as wages fell and conditions worsened. As I wrote in my last article in The Juniper Berry, workers responded by organizing. Through their union, the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (now part of the union, UNITE!/HERE), workers joined with reformers such as future Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandies and others to create a new system to organize industry: the Protocols of Peace, which were created in 1910.

At their core, the Protocols were an effort to modernize and stabilize the industry. The agreement created a uniform wage rate and a floor on working conditions. The goal was to force manufacturers to gain profits through efficient production not sweating workers. This, of course, benefited larger producers who could afford to modernize.The policing agency of the Protocols was the union, who would strike non-compliant shops. For the Protocols to work, however, all shops in the entire industry needed to be covered. This proved to be an impossible task. Created with such high expectations, the Protocols stalled soon after creation.

Late in the afternoon, on March 25, 1911, a typical Saturday at the Triangle Factory, a fire broke out that killed 146 mostly young, immigrant women. Triangle was notorious in the industry. The owners of the factory refused to settle with the union and remained an anti-union shop. They continuously moved and mysteriously suffered from fires. Triangle occupied the top three stories of the Asch Building, on the corner of Washington and Greene in Greenwich Village.The building was a new factory, fire-proof, and not in the tenement district.

Triangle distrusted its workers, feared unions so much, that they chained doors shut.They stored oil cans in the stairwells, and they kept tons of uncollected scraps of cloth around. When the fire was discovered on the eighth floor the workers notified the executives on the tenth floor. No one called the ninth floor.With no notice, workers on the ninth floor were trapped.

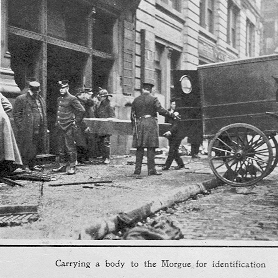

New Yorkers living in fashionable Greenwich Village, such as future Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins, remembered the site that day as dozens of workers jumped to their deaths to avoid the flames. New Yorkers were helpless.Our newest fire trucks, new hook and ladders could not reach the top floors. Fire hydrants lacked sufficient water pressure. Gothamites were horrified and shocked. Many looked for someone or something to blame.

Almost as soon as the flames were out fingers were pointed. Who was to blame, who was responsible. City agencies—fire, building, ECT—blamed each other to deflect responsibility. New York’s “best people,” reformers and the respectable middle class saw the fire as a natural disaster and responded with charity, prayers and a call for action. They saw the need to fire safety, to prevent other such disasters.

Workers, however, saw the events of the fire as connected to the Protocols and the system of industrial democracy in industry. Workers demanded that larger workplace reforms were needed.

What bridged these two movements was an unusual collection of reformers and politicians. The politicians involved were unlikely because they were undistinguished and connected to the political machine of NYC, a machine that was notoriously anti-reform. Al Smith and Robert Wagner, before they became major political forces on NY, were party hacks, hench men of Boss Charlie Murphy of Tammany Hall (The Democratic Party machine). The “Tammany Twins,” as the two were know, became involved by the movements calling for reform because they saw a need and votes. The fire had galvanized NYC’s working class politically like no other event. Large public meetings, funerals and political protests were stirring the pot of Gotham and the two politicians saw an opportunity.

The opportunity, the New York State Factory Investigating Commission (FIC) revolutionized NYS. Created in 1911, the FIC investigated industry and made recommendations to the legislature.

Chaired by Smith and Wagner, the FIC could affect real change. Most investigative bodies made recommendations. But the FIC could use the political tools of Tammany Hall to pass the recommendations into law.Within five years the FIC turned NYC into one of the most advanced and progressive states in America.

Industry was regulated to remove the worst abuses, fire escapes were required, new building codes and inspections were passed and required.

In short, the state picked up where the Protocol had ended.

The FIC was the embodiment of the best of liberalism. It reflected the recognition that the state had a social and economic responsibility to protect its citizens from the extremes of industry. It conserved human capital and shaped industry to become more modern, to rely less on cheap and exploited labor. Years after the Triangle Fire Frances Perkins, New Deal Secretary of Labor was asked where the New Deal come from and she said it all started at Triangle.

So as the anniversary of this tragedy approaches we need to reflect on the terrible and needless loss of life and imagine what might have been.

But,we need also to see that New York rebounded from this tragedy, gained strength from the pain and made something new. This is a lesson we need in this dangerous and troubling time.

Richard A Greenwald is an Assistant Professor of History and Assistant Head of Humanities at the United States Merchant Marine Academy in Kings Point, NY. He is a graduate of Christ the King High School, Queens College, and received his PhD in history from New York University. He books include Sweatshop USA and the forthcoming Triangle Fire, the Protocols of Peace and Industrial Democracy in Progressive Era New York.

He is available to speak to civic groups as part of the “Speaker in the Humanities” Program of the New York Humanities Council. Information about Dr. Greenwald and how to purchase his books are available from www.richardgreenwald.com. His views are not those of the US Merchant Marine Academy, the Department of Transportation or the federal government. They are his alone.