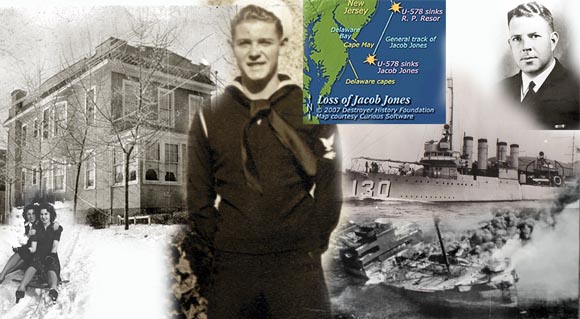

In the 1930’s and 40’s, Eddie Hoyt lived on the 2nd floor of a two family house on the corner of 58th Road and 74th Street in Maspeth. An only child, his father Harold was a train engineer whose daily runs would regularly take him within blocks of their five-room apartment. Every time his locomotive would pass near Caldwell Avenue, Harold Hoyt would sound the train’s whistle to signal his wife and son that dad was nearby. Most of Maspeth also knew when Mr. Hoyt was near as the loud whistle would echo throughout the quiet neighborhood. When Eddie was younger, he would often run down the street to catch a glimpse of his father’s train as it rumbled past, bellowing smoke that would dissipate slowly above the trees.

Mrs. Hoyt would challenge Eddie saying he would not make it down to the railroad bridge in time to see his father. However, more often than not he would make it in time since his father would slow the train as it neared Maspeth so the boy could see his father’s train.

Mrs. Hoyt was well known in the community for her baking, especially pies whose aroma would fill the house and environs and treat passersby.

When Eddie turned 18 he had grown into the All-American boy – handsome, blond, and blue eyes. In fact neighborhood girls like Anne DeCola, who lived across the street from Eddie, described him using one word, “gorgeous!”

Like his Father Before Him

Like so many American young men, Edward Hoyt dreamed of serving in armed forces and particularly in the Navy to “see the world.” He enlisted just months before the outbreak of World War II. Eddie’s Father Harold was a World War I veteran and Eddie wanted to follow in his father’s footsteps.

But like hundreds of thousands of mothers, Mrs. Hoyt worried about her son’s safety. Her worries were somewhat alleviated when Eddie, a Radioman Third Class, was assigned to the U.S.S. Jacob Jones, a destroyer used to patrol U.S. coastal waters from Canada to the mid-Atlantic states. He would at least be close to home.

A Stormy Beginning

On January 14, 1942, the Jacob Jones joined a convoy, headed for Iceland. The convoy encountered a violent storm; heavy seas and winds of force 9 that scattered its ships’ convoy. Separated from the convoy, the Jacob Jones steamed independently for Hvalfjordur, Iceland. Though hampered by a shortage of fuel, an inoperable gyro compass, an erratic magnetic compass, and the continuous pounding of the storm, the Jacob Jones arrived on January 19th. Relieved, Eddie and his shipmates felt they were “baptized” in life at sea.

Five days later, their ship again escorted three merchant ships to Argentia, Newfoundland. Once again heavy seas and fierce winds separated the ships; and the Jacob Jones continued toward Argentia with only one Norwegian merchant ship. On February 2nd, she detected and attacked a German submarine, but her depth charges yielded no visible results.

Arriving in Argentia on the February 3rd, the Jacob Jones departed the following day and rejoined Convoy ON-59, bound for Boston. Reaching Boston on February 8th, the Jacob Jones received a week of repairs. She sailed on the 15th for Norfolk and 3 days later steamed from Norfolk to New York.

After another harrowing experience at sea, Eddie would be heading home for some well-deserved rest and relaxation. But the crew of the Jacob Jones would not have a long leave.

Tremendous Loss of Merchant Ships

In an effort to stem the losses to Allied merchant shipping along the Atlantic coast, Vice Admiral Adolphus Andrews, Commander of the Eastern Sea Frontier established a roving ASW patrol. The Jacob Jones, with Lt. Commander Hugh David Black in command was selected for the patrol and departed New York on February 22nd for this duty.

Eddie & Mary

As Eddie was leaving home he found enough time to propose to his sweetheart, Mary Rooney, who lived down the street. Mary was surprised by the sudden proposal but quickly said yes and the two 19-year olds parted but were certainly on cloud nine.

Once at sea, radioman Hoyt was called to duty immediately out of New York Harbor. While passing the swept channel off Ambrose Light Ship, Sandy Hook, N.J., the Jacob Jones made a possible submarine contact and attacked immediately. For 5 hours the Jacob Jones crew ran 12 attack patterns, dropping some 57 depth charges. Oil slicks appeared during the last six attacks but no other debris was detected. Having expended all her charges, the Jacob Jones returned to New York to rearm. A subsequent investigation failed to reveal any conclusive evidence of a sunken submarine.

Looking Forward to Shore Leave

It had been known by Mary that Eddie was due for shore leave and had planned to come home to celebrate his engagement with his fiancée. However at the last minute a shipmate begged Eddie to trade him so that he could go instead. Eddie agreed and would take his leave the next time they arrived in New York.

On the morning of February 27th, the Jacob Jones with 141 men aboard departed New York harbor and steamed southward along the New Jersey coast to patrol and search the area between Barnegat Light and Five Fathom Bank. Shortly after her departure, she received orders to concentrate her patrol activity in waters off Cape May and the Delaware Capes. At 15:30 she spotted the burning wreckage of tanker R.P. Resor, torpedoed the previous day east of Barnegat Light; Jacob Jones circled the ship for 2 hours searching for survivors before resuming her southward course. Cruising at a steady 15 knots through calm seas, she reported her position and then commenced radio silence. A full moon lit the night sky and visibility was good; throughout the night the ship completely darkened without running or navigation lights showing, kept her southward course.

U-Boat in the Area

Meanwhile the German U-boat 578 that had attacked and sunk the Resor was still in the area. U578 left St. Nazaire in occupied France on February 3rd as part of Operation Drumbeat, (U-boat operations off the eastern seaboard of the United States).

At the first light of dawn February 28, 1942, U-578 spotted the Jacob Jones first and fired a spread of torpedoes at the unsuspecting destroyer. The deadly “fish” sped undetected and two or possibly three struck the destroyer’s port side in rapid succession.

The first torpedo struck just aft of the bridge and caused massive damage. Apparently, it exploded the ship’s magazine; the resulting blast sheered off everything forward of the point of impact, completely destroying the bridge, the chart room, and the officers’ and petty officers’ quarters. As she stopped dead in the water, unable to signal a distress message, a second torpedo struck about 40 feet forward of the fantail and carried away the aft part of the ship above the keel plates and shafts and destroyed the after crew’s quarters. Only the midships section was left intact.

The explosions killed all but 25 or 30 officers and men, including Lt. Commander Black. The survivors, including a badly wounded, “practically incoherent” signal officer, went for the lifeboats. Oily decks fouled lines and rigging and the clutter of the ship’s strewn twisted wreckage hampered their efforts to launch the boats. The Jacob Jones remained afloat for about 45 minutes, allowing her survivors to clear the stricken ship in four or five rafts. Within an hour of the initial explosion Jacob Jones plunged bow first into the cold Atlantic; as her shattered stern disappeared, her depth charges exploded, killing several survivors on a nearby raft.

At 08:10 an Army observation plane sighted the life rafts and reported their position to Eagle 56 of the Inshore Patrol. By 11:00, when strong winds and rising seas forced her to abandon her search, she had rescued 12 survivors, one of whom died en route to Cape May. The search for the other survivors of Jacob Jones continued by plane and ship for the next 2 days; but none were ever found. Among the men that went down with the Jacob Jones were the Parker brothers, Reed, yeoman 2nd class and Roy, seaman 1st class, from Warren Street in Westboro, Maine.

The following day in Maspeth, Mrs. Hoyt received a telegram from the U.S. Naval Department. Her only son was one of the causalities of the U.S.S. Jacob Jones. Her knees buckled and she screamed… “my God, no!” For months Mrs. Hoyt could be heard from her 2nd floor apartment sobbing for hours on end. Mr. Hoyt was so devastated by the news that his beloved son was gone that he would never be his usual self. And never again would residents hear the sound of his locomotive’s horn as it approached Maspeth. Eddie Hoyt was the first WWII casualty from Maspeth.

Neighbors too were stunned that a boy so full of life, so young and so close to home could be a victim of such a terrible tragedy. Eddie Hoyt had died in the service of his country defending his homeland in the Battle of the Atlantic. In the days and years that followed, Maspeth cried many more tears for their lost and brave sons.

Today as you pass the CSX railroad tracks on Caldwell Avenue, think of Eddie Hoyt, and all the young men who had so much to live for, yet in the face of extreme peril, performed heroically and paid the ultimate price.

Now as the survivors of World War II are leaving us in greater numbers, we must preserve their memories and accounts of those who gave so much in the defense of freedom.

Eddie’s body was never found. His name appears on the the World War II East Coast Memorial, located in Battery Park at the southern end of Manhattan Island. It is about 150 yards from the South Ferry subway station on the IRT Lines and overlooks the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor. It stands just south of historic Fort Clinton on a site furnished by the Department of Parks of the City of New York. This memorial commemorates those soldiers, sailors, marines, coast guardsmen, merchant marines and airmen who met their deaths in the service of their country in the western waters of the Atlantic Ocean during World War II. Its axis is oriented on the Statue of Liberty. On each side of the axis are four gray granite pylons upon which are inscribed the name, rank, organization and state of each of the 4,609 missing in the waters of the Atlantic.