The Maze – and shock over a killing there more than a year ago – refuse to go away.

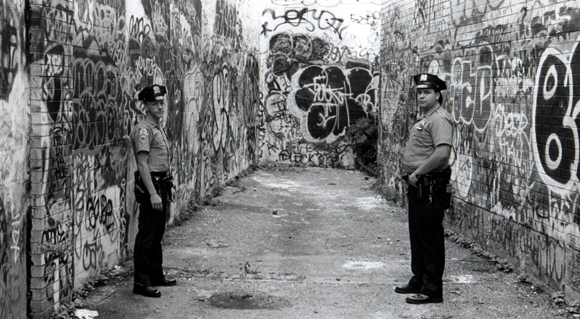

For years the zigzag passageway between warehouses on 74th Street near 52d Court in Maspeth has had an exciting, forbidden appeal to youngsters, who used it as a hangout, a hideaway and private graffiti gallery.

On Dec. 6, 1992, the police say, 16-year-old Ryan Dionne was kicked, then stabbed 18 times, in an angry dispute over money. He died on the spot, in the presence of horrified friends.

In the aftermath, Dale Ramphal, 17, was charged with murder. Local officials declared the Maze dangerous and demanded it be shut down, and the landlord, Louis Sheriff, erected a concrete block wall with a locked door and gave the police the key.

But now neighbors are reliving the case as they debate Mr. Ramphal's recent acquittal after a five-week trial. And a new push is on to seal the Maze, which still attracts teen-agers.

“It's a horrible place, not safe for anyone,” said City Councilwoman Karen Koslowitz. She wants it somehow removed or permanently sealed. “I don't want to ever have to revisit the Maze,” she said, “or have anything horrible happen there again.”

At the front enclosure of the Maze, someone glued the lock, so the police can't get in with the key. The top five rows of concrete blocks have been broken off, enabling teen-agers to scale the wall more easily. And the back entrance, along the adjacent Conrail tracks, remains accessible.

Police at the 104th Precinct say that except for the slaying, they are not aware of serious crimes at the Maze. Yet many neighbors say it draws youths and some adults, with drinking, drugs, carousing and fighting that leave broken bottles and even bullet casings — raising fears that more serious trouble could reoccur.

And if it did, the acquittal of Mr. Ramphal — in a case where four eyewitnesses testified against him — has undercut their faith that justice will be served.

Patricia Dionne, mother of the victim, called the verdict outrageous. After the acquittal on Jan. 12, she said, “I walked out with all those kids. They sobbed and cried. Everything fell apart. It was awful.”

One witness, Eric Ballek, who lived across the street from Mr. Ramphal, said he had tried to stop the attack. Mr. Ballek suffered post-traumatic stress syndrome with disrupted sleep and nightmares, his mother, JoAn Ballek, said, requiring intensive psychotherapy. “When the verdict came in, he was devastated all over again,” she said. “What scares us now is this guy got off and is around.”

Mr. Ramphal did not respond to messages left with his lawyer.

Debra Lynn Pomodore, the assistant district attorney who prosecuted, said: “We had absolutely no doubt this was the person who did it. Our evidence was overwhelming, with four eyewitnesses who knew him.”

Critics of the verdict variously blame faulty investigation and prosecution, adverse actions by the judge and adroit moves by the defense lawyer, Todd D. Greenberg. He challenged the credibility of the four young witnesses, portraying them as graffiti vandals. He also contended that the kick to the head may have killed Mr. Dionne, not the stabbings as the medical examiner and indictment specified. And he pointed out the knife that was recovered was never tested for blood.

“I saw the whole thing — I don't know what that jury was thinking,” said Stephen Davis, who called the ambulance to the murder scene. He and other witnesses expressed dejection that the jury apparently did not believe them. His mother, Carol, said: “The kids have lost faith. We told them to tell the truth, and they did what was right. But the system failed — what do I say now?”