The first of the ancient roads to be developed in Maspeth was an Indian pathway used by the Dutch colonists. This path ran from the tide mill belonging to Burger Jorrissen to the shore of the East river where the Ferry House stood. When the English settlers came in 1642, they extended this pathway to their settlement at the head of the Newtown Creek. They called the pathway the Ferry Road. Parts of 57th Avenue (called Creek Street and also, Old Flushing Avenue) cover this ancient path today.

When the towns of Hempstead (1644) and Flushing (1645) were begun, the Ferry Road was extended further to run over parts of modern Maurice Avenue, Calamus Avenue and Queens Boulevard, in a northward direction leading toward towards the new towns. The road was still called the ‘Road to the Ferry.’

After the village of Newtown was established in 1651-1652, a new branch of the Ferry Road was cut through and the branch route lay along present Flushing Avenue, up present Grand Avenue, and down to Broadway at Queens Boulevard. This branch of the Ferry Road was called, “The Highway to Newtown.” They also called it the “Upper Road to the Ferry” and they then called the old Calamus Avenue route “the Lower Road to the Ferry.” Settlers from Maspeth who were traveling to Flushing called the upper route “The Flushing Road.” The various names the early settlers gave to the same roadway makes it difficult to understand some accounts of colonial doings in our area.

Old Fresh Pond Road (which is now 61st Street) was in use by 1680, and it led the traveler south to a large fresh water pond which lay in the area of Ridgewood in colonial times. It also led to the disputed hay meadows and to a few isolated plantations in the Ridgewood area. By means of this road, one could reach the Jamaica Road, called Rustdorp by the Dutch, while Flushing was called Vlissingen. All of Newtown Township was called Mispat by the Dutch.

Another important early road was Laurel Hill Boulevard. It ran to the Dutch farms at Long Island City and was reached from Maspeth by parts of 58th Street and parts of Maspeth Avenue. By the year 1656, 58th Street running up along present Mt. Zion Cemetery passed the dwelling and farm of Captain Richard A. Betts, at the South East corner of the cemetery. His house served as a meeting place for the Quakers of English Kills until their own meeting house could be built. (The Betts cemetery still lies inside Mt. Zion Cemetery and many of the old grave markers remain readable.)

The House of Captain Richard Betts, built 1656, or shortly before, stood until 1898 at the present Mt. Zion Cemetery. The first roof of this house was of thatch.

By the beginning of the Revolutionary War, parts of the following roads were in use although they were un-named in most case: Flushing Avenue, Maspeth Avenue, Grand Avenue, Maurice Avenue, 58th Street, 59th Place, Laurel Hill Boulevard, Rust Street, Calamus Avenue, Fresh Pond Road, 69th Street (heading south,) Brown Place, Juniper Valley Road, Dry Harbor Road, Myrtle Avenue, Cooper Avenue (Glendale,) Woodhaven Boulevard, and 57th Avenue at the eastern end of Maspeth, today, which was called the North Hempstead Plank Road.

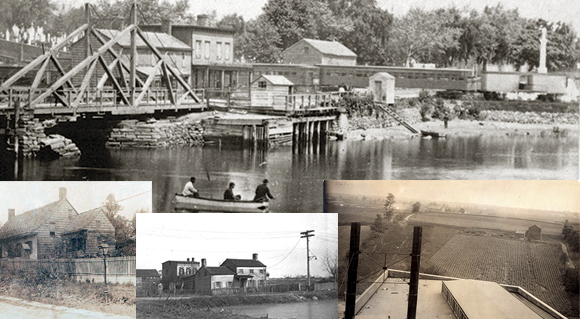

The Newtown Creek was crossed by means of a ferry operated by Humphrey Clay, the Elder, in 1670. The landing of the Bushwick shore was at Meeker Avenue and the landing at the Maspeth shore was at Penny Bridge Station. By the middle 1700s, a primitive bridge spanned Newtown creek at this spot which would be replaced in 1814 with a stronger, more permanent bridge. The new bridge charged a toll of one penny to pedestrians crossing, and received the name of “Penny Bridge”.

The roadways of the colonial period were largely developed from pathways used by the Indians. These old paths wound around the hills and swamps of the Maspeth region in what might seem to be a round-about manner, but we must remember that land features of our area were nearly impervious to modification with the primitive implements available to the early settlers.

Three great swamps posed an obstacle to road construction during the early years. The biggest swamp called the Cripple Bush, was at the Newtown Creek and spread out around the Bushwick shore line, over toward Greenpoint. It also spread around Maspeth Creek, and our Indians called this boggy, treacherous swamp the ‘bad water place.’

The great Juniper Swamp began on the east side of 69th Street at 61st Avenue, and continued toward Middle Village where it grew denser and lay under the present area of Juniper Valley Park, as well as under the houses and streets of the present Eliot Avenue. Cating Pond in 1920, one of the many fresh water ponds near modern 69th Street heading south, and on up to part of Juniper Valley Road.

The last great swamp in our region was called the Wolf Swamp, because hundreds of these predators infested its depths. A wet, wooded land, Wolf Swamp lay in modern Woodside behind Calvary Cemetery and south of Laurel Hill Boulevard. It was impassable until 1866-1867, when settlers of Woodside cut some of the trees and drained the land. Wolf swamp sheltered the animals driven out of inhabited areas of Newtown Township during the Dutch rule, when a reward of ‘one Indian Coat’ was offered to any man who would bring in the head and ears of a wolf.

Fresh water ponds lay everywhere in colonial Maspeth. There were very large ponds, such as Scudder’s Pond near 58th Street and Maspeth Avenue, Way’s Pond near the Rust Street underpass of the Railroad. There were two large ponds along 69th Street, one at 53rd Avenue and one at 69th Street near Caldwell Avenue. A large pond was located on Metropolitan Avenue near Pleasantview Street, and nearly every farm in the region had its own stream or brook for watering cattle.

Cating Pond in 1920, one of the many fresh water ponds of old Maspeth which were filled to permit construction of homes.

The people of colonial Maspeth were dwarfed by the vastness of the new land they tenanted. Great stands of timber, white pine and oak, closed their branches to the sky forming a deep and verdant forest. The ridge area of Ridgewood and Brooklyn presented a natural barrier to settlement on the south, while the bay at Hallet’s Cover, Astoria, marked the furthest reaches of northern exploration. At this period in the development of Maspeth, people were greatly at the mercy of the environment.