The two stories you are about to read are those of NYPD officers who made the ultimate sacrifice in service to our neighborhoods during the holidays. While we do not enjoy presenting tragic stories this time of year, it’s important to remember that all these decades later there are still people putting their lives on the line to protect us who are not able to celebrate holidays as others do. May they all return safely to their families at the end of their tours.

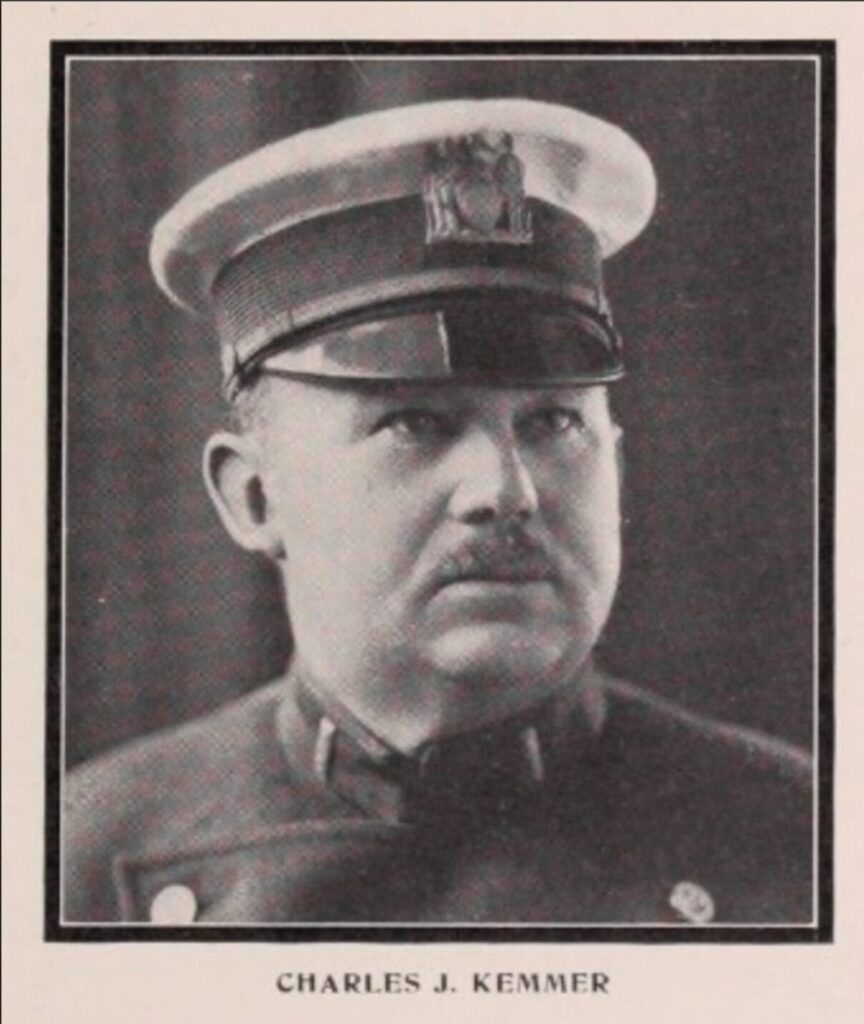

Lt. Charles Kemmer

Lt. Charles Kemmer was working the desk of the 54th Precinct that day in September 1927 when the disturbing call came in that Patrolman Henry Meyer had been shot by a gunman who was part of a duo that robbed two women at Beth Elohim Cemetery along Cypress Hills Street. He dispatched every available police officer and detective to the scene and the crime was quickly solved, with suspects apprehended. Kemmer attended the funeral of the respected fallen officer, who by all accounts was one of the finest cops in the command.

Three months later, the precinct would dispatch units to the cemetery belt again, this time to search for Kemmer’s killer. It would be a very somber holiday season at the 54th Precinct in 1927.

Charles Kemmer was born in Germany in 1876. He joined the NYPD in 1901. In 1916, he was promoted to sergeant and to lieutenant in 1925. On December 21, 1927, Kemmer put up and decorated the family Christmas tree at his home in Richmond Hill with his wife Kathleen and children, Kathleen, age 14 and Charles, age 12. The following morning, after putting a few finishing touches on the tree, he boarded the Myrtle Avenue trolley on his way to work the day shift at the desk of the 54th Precinct house, which today is the 104th Precinct.

At around 7:30am, Kemmer exited the trolley at Kossuth Place, which today is part of Cypress Hills Street, and began to walk toward the stationhouse. At Halleck Avenue, now 70th Avenue, stood a restaurant. Inside the restaurant, two holdup men had tied up two employees in a back room after robbing the register of $75, one employee of $14 and the other employee of an expensive stickpin. As the gunmen were making their getaway, the employees screamed for help. This caught Kemmer’s attention, and he ran into the restaurant. He punched one suspect in the jaw, but the second suspect pumped five bullets into Kemmer’s head and abdomen.

The shooter ran out and hopped into a red roadster where his accomplice was waiting. Kemmer, although critically wounded, was able to write down the license plate number of the getaway car before collapsing.

The gunshots could be heard at the Catalpa Avenue station house and officers ran over to the scene to find Kemmer in grave condition. Police were mobilized from surrounding precincts to help look for the suspects in the cemeteries along Cypress Hills Street, in the direction that witnesses reported the car was seen heading, the same location where Ptl. Meyer had been felled earlier in the year. They also searched trolleys and local elevated subway cars and stations. An ambulance was called for Kemmer, but the vehicle turned over en route and was delayed. There was some hope at Wyckoff Hospital once he arrived that Kemmer would pull through, and every officer at the precinct offered to donate blood for a surgery to remove the bullets. As he lay in grave condition, he told detectives to retrieve the paper containing the license plate number from the counter of the restaurant. Unfortunately, Kemmer never made it to the operating table, dying of his wounds hours after the shooting.

The license plate number proved to be the key to solving the case. Sharp-eyed Manhattan traffic Patrolman James W. Hibbard spotted the red roadster car with the license plate 15365 traveling down Hudson Street on December 23rd and recognized it as the wanted vehicle from a bulletin wired to every precinct. He pulled it over and arrested the occupants, a man and a woman. The man was 24-year-old Edward Byrne and the woman was his girlfriend, a young unidentified lady “from a good family” in Ridgewood who police soon determined had not been involved in the crime. Byrne confessed to his role in the incident. He was the perp who Kemmer had punched in the jaw. He said he only participated in the holdup to get money to buy his sweetie a nice Christmas present. He fingered 40-year-old George Appel as the murderer. Appel was picked up at his Brooklyn apartment without incident but claimed he was not the triggerman. The murder weapon was recovered under a mattress along with the stolen loot. Both men signed written confessions as to having been involved.

It is hard to imagine the horror that Kathleen and her children must have endured that Christmas. An inspector’s funeral was held at St. Benedict’s Church for Charles on December 27, and he was buried at St. John Cemetery. He was posthumously promoted by the police commissioner. Kathleen received $500 from the police fund immediately and $5000 in monthly payments of $50. She also received a full year’s salary and a life pension of $1650. Charles had left $3000 to his wife in his estate which she put part of toward the children’s education.

After the holidays, charges were brought against the men. Their swift trial took place in January 1928. Byrne, while the jury was deliberating, pleaded guilty to second-degree murder, robbery, grand larceny, and assault, and was sentenced to 35 years to life in prison. Appel was convicted of first-degree murder and after an unsuccessful appeal, went to the electric chair at Sing Sing in August 1928. For his heroism, Ptl. Hibbard was promoted to Detective Second Grade.

Ptl. Joseph Jockel

Joseph Jockel was a member of the NYPD for 7 years. He started in 1922 at the 60th Precinct (later the 110 Pct) in Elmhurst and was promoted to Motorcycle Squad 1, Manhattan, which covered Central Park, in 1925. At the age of 32 years old, he was married and lived with his family at 215 Monitor Street in Greenpoint. He celebrated Christmas 1929 with his family, which included his wife Sara and their children, Verna, age 10, Joseph, age 8, Kenneth, age 5 and Muriel, age 3.

There had been a storm which caused dangerous muddy conditions in the park, so Jockel was temporarily assigned to foot patrol in his old precinct. The evening of December 28, Jockel arranged to visit his widowed mother, Mae, before his shift. She lived on Juniper Ave (69th Street) in Maspeth. They parted ways when it was time for Joe to leave for his shift. They walked together down to the car barns so Joe could hop on a trolley to clock in at the precinct house in Elmhurst. Mae proceeded down Grand Avenue toward the Atateka Democratic Club (today the Kowalinski Post) which was hosting a children’s holiday party.

It was the week between Christmas and New Year’s and after 9pm, so the trolleys were scheduled few and far between. While Jockel was waiting for his car to arrive, he saw a taxi speed past him riding on a flat tire. His police instincts kicked in and he realized this looked suspicious. He commandeered a private vehicle and ordered the driver to follow the taxi down Grand Avenue. The taxi was overtaken, and Jockel jumped out to investigate. As the men exited the vehicle, seemingly cooperating, one of them shot Jockel three times, hitting him in the head and neck. While Jockel tried to crawl over to a callbox to alert the precinct, the 4 men took off in the vehicle. Jockel never made it to the callbox, collapsing dead in the muddy street.

Officers arrived at the bloody scene and covered Jockel’s face with a coat. The women at the Democratic Club, including Mae, had heard the commotion and came out to see what was going on. Mae recognized a ring on Joe’s hand, knew it was her son under the jacket and became inconsolable.

The car was located in Woodside with the occupants nowhere to be found. Later, the driver was discovered bound and gagged by the side of a road and had quite a story to tell. He said his cab was hailed by three men in Flushing who asked to be driven to Woodside. While one of the gunmen covered the driver, the other two robbed a pharmacy. They made it back to the car with the $60 they stole and ordered the driver to take them to Brooklyn. It was during the getaway that the tire went flat, and Jockel had spotted the car.

The Jockel family was faced with the prospect of starting 1930 without their breadwinner. Unlike higher ranking officers, in 1929 there was no payout to families of slain officers. Sara was left penniless with four children to care for and raise alone. A funeral mass was held at St. Cecelia’s in Greenpoint and Jockel was buried with full honors at Calvary Cemetery on January 2, 1930.

The manhunt was in full swing. Suspects picked up for other robberies were questioned at length about their whereabouts as well as those of their known accomplices. Detectives were convinced they had the gunman when they brought in Fred Teti, a recidivist perp known to them with a rap sheet dating back to 1922. Teti had been charged in the past with larceny, assault, gambling, robbery, and homicide. Except for three fines, charges were dismissed every time. He was a slippery one, and witness tampering may have been involved to achieve the desired result. For Jockel’s murder, Teti maintained his innocence and could not be identified by the taxi driver, therefore he was released without charges. Jockel’s killers were never brought to justice, however, someone pumped 17 bullets into Teti in 1932, so if he was in fact the gunman, he did receive a bit of street justice.

Kenneth Jockel followed in his late father’s footsteps and joined the NYPD after serving with the Army Air Force during WWII. He achieved the rank of lieutenant before retiring.

Juniper Park Civic Association and Newtown Historical Society have recommended Ptl. Henry Meyer, Lt. Charles Kemmer and Ptl. Joseph Jockel for 2023 honorary street co-namings so their sacrifices will continue to be remembered for decades to come.