Police were summoned by bakery truck driver Martin Grauerholtz during the morning hours of Sunday, September 2, 1928, after he happened across a body at the desolate intersection of Betts and Borden Avenues, outside Mount Zion Cemetery. Finding a dead body in the western end of Maspeth was not unusual, as it was known as a place to murder and dump bodies. Max “Skinny the Rat” Goldstein had been murdered nearby less than 2 months earlier (details of which may be found in the March 2021 Juniper Berry). But this latest case was much, much different. Goldstein was a street thug with a rap sheet a mile long while the more recent victim, 51-year-old William D’Olier, was a wealthy and well-respected member of high society, with a wife, two young children and a lovely home in tony Pelham Heights in Westchester County.

D’Olier was a sewer engineer by trade, and of late had been president of the Sanitation Corporation located at 420 Lexington Avenue, aka the Graybar Building, in Manhattan. The company had installed the machinery at the Maspeth and Jamaica Bay sewer plants which had been built by Awixa Corporation of Islip, Long Island. The entire project was involved in a graft scandal involving former Queens Borough President Maurice Connolly, who had resigned when he realized he was under investigation. Awixa had mysteriously been robbed of important documents during the investigation and two witnesses who were to be called to testify at Connolly’s trial had already turned up dead in other parts of the city. D’Olier had also been scheduled to testify, and now he was also dead.

By now, you are probably connecting the dots and forming a conclusion as to what happened. But that’s not how investigators proceeded. There were two theories and conflicting accounts of the condition of the body as well as charges of unprofessional crime scene processing, the drama of it all playing out in the papers for weeks.

D’Olier’s body was found at the bottom of a small hill, partially concealed by brush. His feet were pointed up and his head, with a bullet hole in it, was resting atop a rock at the bottom of the hill near the roadbed. He was clearly visible from the street. His body was still warm at 6am, indicating that death had occurred no more than two hours prior. He was dressed in a suit, which was dirty and disheveled. In his hand was an antique .32 caliber revolver. His identification, jewelry and money were found in his pockets, so detectives quickly eliminated robbery as a motive. Police were down to two angles: this was either a suicide or a hit.

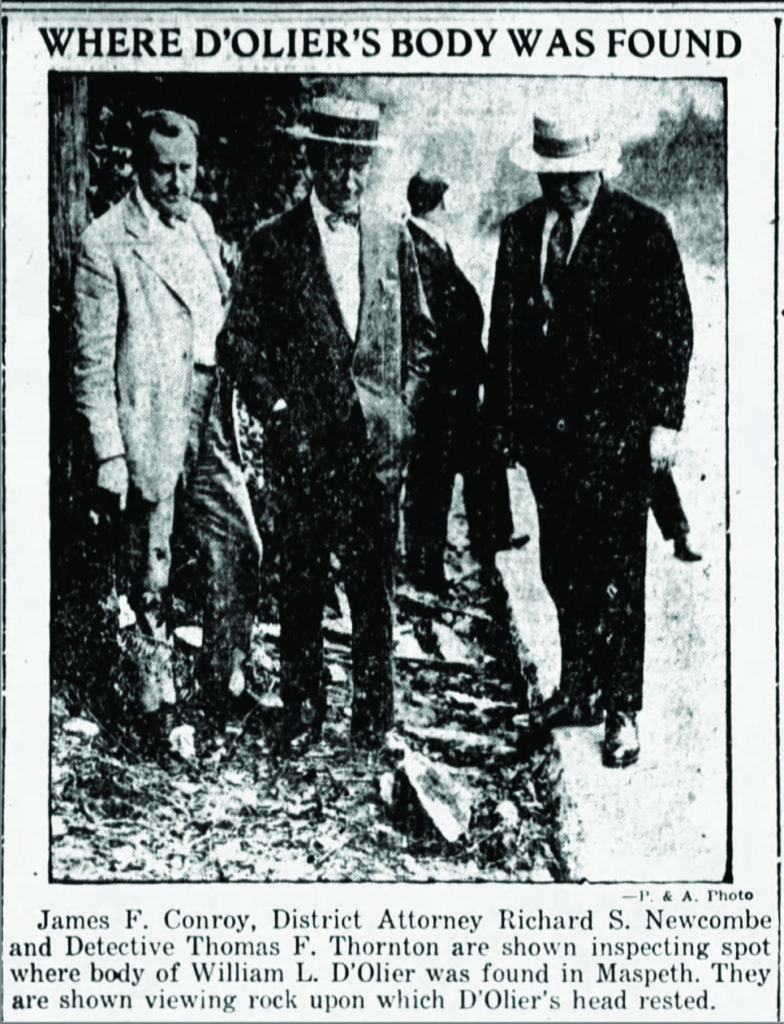

The suicide theory was bolstered by the fact that the gun was determined to have been owned by D’Olier and the fatal shot was fired from it. But fingerprints could not be obtained from it because when it was discovered at the crime scene, the cops present, who had never seen such an interesting firearm, had passed it around amongst themselves in curiosity instead of handling it according to evidence gathering protocols. Original news reports stated that there was no pool of blood visible at the scene, which would have been expected had D’Olier committed suicide. But later, District Attorney Richard Newcombe, who had responded to the scene, claimed there was a rather large pool of blood under D’Olier’s head, over which he had spread some dirt in order to conceal it from the public. So, this eliminated the possibility that D’Olier had been murdered elsewhere and his body dumped in Maspeth. He definitely had died where he was found.

Detectives traced D’Olier’s movements in his final hours. He had kissed his pregnant wife goodbye on Saturday morning, and headed to Manhattan carrying a change of clothes and a briefcase full of papers. He checked into the Plaza Hotel. At 6pm, he had made a long-distance business call to Kentucky. He signed into the Graybar Building under his attorney’s name at 7pm. He was preparing to be a star witness at the sewer trial and in fact had been subpoenaed while on business in South America two weeks prior, prompting his return home. D’Olier changed into a different suit at his office. He had a meeting with his attorney, Gilbert Waldrop, and before leaving told him that he was heading out to Queens to meet with a business associate. That was the last time he was seen alive.

Detectives did not find his briefcase or the papers that were inside them, believed to be duplicate copies of contracts and other evidence, in his hotel room. A search of safety deposit boxes in his name at several banks came up empty. It was also discovered that D’Olier’s perceived wealth was an illusion. He only had about $500 left to his name and his company was in financial ruin. He was worth more dead than alive as he had an $85,000 life insurance policy which would have supported his family in the event of his death. Although the DA was leaning toward murder, suicide couldn’t be ruled out under the circumstances. But his attorney said he was in good spirits when he spoke with him, as he believed he was a on the cusp of signing a lucrative $15M contract in Louisville, KY that would have potentially made the Sanitation Corporation solvent again.

In his hotel room, cops had discovered another firearm in a holster. Witnesses described D’Olier as having expressed fear for his life, always carrying a revolver for protection. Waldrop also revealed that D’Olier had donated $5,000 of his company’s money to a “war chest” which was really a bribe fund meant to keep a witness from turning state’s evidence. D’Olier himself was never a target of the sewer investigation, however. Connolly was interviewed by the DA regarding his relationship with the victim but never charged.

Detectives were investigating how and why D’Olier ended up in a desolate section of Maspeth in the wee hours of Sunday morning. He could not have taken the trolley as there was no overnight service on the Cemetery Line. A gravedigger working midnights recalled seeing an expensive looking cream-colored vehicle parked for hours near the scene but when he left at the end of his shift the car had disappeared. It seemed that D’Olier had been in the company of someone who had brought him there to kill him, but who was it? At one point a witness came forward claiming to have seen a mystery woman with D’Olier. Police thought she may have possibly lured him to his death, but her existence was never confirmed.

The medical examiner testified at a grand jury that the gun used to kill D’Olier was not pressed against his head but held about 2 inches away. He did not believe the trajectory of the bullet was consistent with suicide. He said the position of the gun was such that it was gently resting inside his hand, and that if he had committed suicide, his finger would have been locked around the trigger with the rest of his hand gripping it. He also said there was a large 6-inch tear in the back of D’Olier’s jacket and he had 2 cracked ribs, indicating an assault. The grand jury declared the death a homicide and issued a rebuke to the police for the bungled handling of the crime scene. Unfortunately, that’s as far as justice went for William D’Olier. Police never found his killer or confirmed that the murder was definitively linked to the sewer scandal.

Queens Borough President Maurice Connolly was convicted of conspiracy to defraud the government about six weeks after D’Olier’s death. Others involved were also convicted. Connolly served a year in prison from 1930-1931 after losing an appeal. He suffered a series of strokes, the first of which happened during his incarceration, and died in 1935.