Dr. Asa Bernstein found his way to Middle Village and opened a medical practice in a stately house on Hinman Street near Metropolitan Avenue. Since the major hospitals were far away, Dr. Bernstein had an annex added on to the back of the house which would serve as a mini hospital. Dr. Bernstein, as most family practitioners of that era, performed minor surgeries such as tonsillectomies, removing adenoids, setting broken bones, and stitching all kinds of wounds. Moreover, many children were born at his lying-in facility, tended by his wife who was also a nurse. It almost was a badge of honor for one to be able to proclaim that they were born in Dr. Bernstein’s hospital. To digress for a moment, I would like to tell a Middle Village folkloric tale.

On a cold December 11, 1936, the same day that King Edward abdicated from the throne of the British Empire for “the woman he loved,” Eva Teicher walked from her home to Dr. Bernstein’s lying-in hospital and gave birth to a cute little baby boy. Since Eva already had four sons, she turned her head to the side, disappointed that she would never have the daughter that would have completed her life. “A son is a son until he takes a wife, a daughter is a daughter for the rest of your life!” How true these old adages are!

In any case, she walked home with the baby wrapped in swaddling of that era. When she arrived home, she deposited him in a make-shift cradle (the proverbial dresser drawer), and told our next-door cousins, Phyllis and Shandy, that they could have a real-life doll to play with, which they did. His name was Herby.

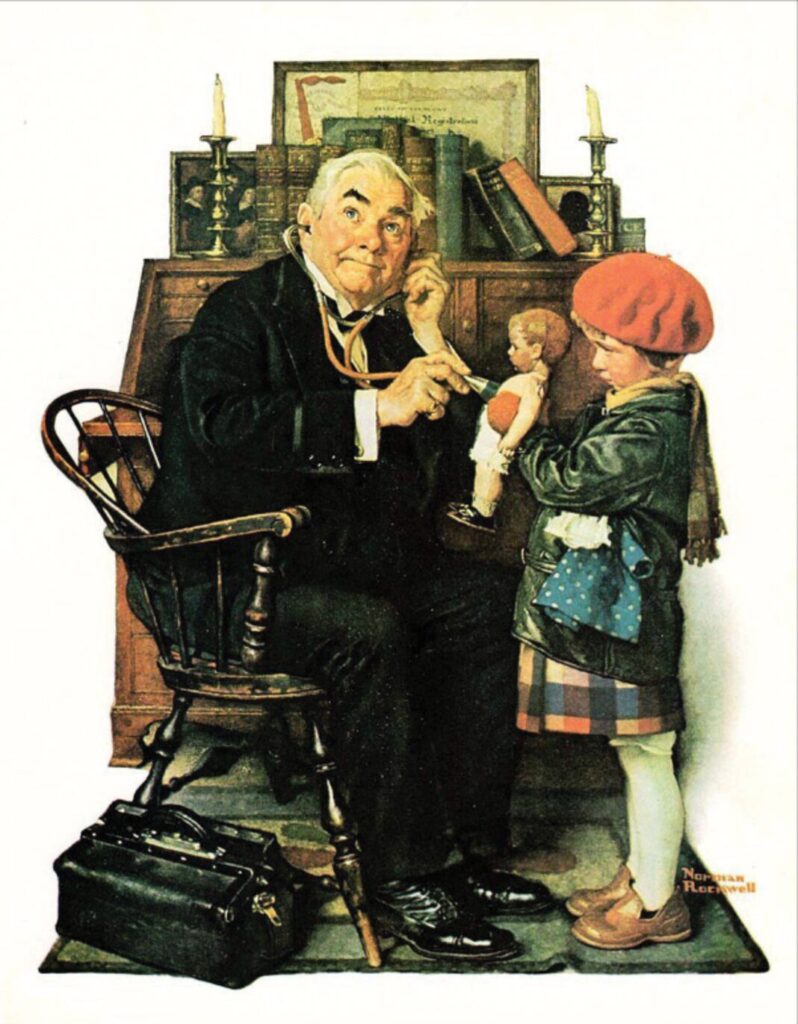

Getting back to Dr. Bernstein: He was a kindly man as I remember him. I recall being examined by him in his office and I distinctly recall his gentility and warm smile. Although he had limited medical resources available to him, he was revered by his patients who accepted what life brought them. Perhaps his wonderful bedside manner was the best palliator of that era. A few years hence, I recall seeing the famous Norman Rockwell illustration of a child being examined by her doctor and I said to myself, “That’s Dr. Bernstein!” Healthcare was just not an issue in those days. One went to the doctor, was examined, diagnosed, advised, prescribed and the patient meekly asked the doctor “How much do I owe you?” almost as an afterthought. “Oh, give me two dollars.” End of discussion – no receptionist, no requests for medical insurance cards, no billing clerks, no threats of withholding services. Just a warm, humane understanding between doctor and patient.

If a family was indigent, the doctor would say, “Don’t worry about it, you can pay me some other time.” The same thing was true of hospitals. You paid the bill if you had the assets. You were never dunned or hounded for payment. How does one explain this generosity considering today’s brouhaha about medical costs? First, small town doctors for the most part were held in high esteem and seemed to love their profession. It was also relatively inexpensive to open an office since there wasn’t expensive equipment to buy. Certainly, malpractice insurance was not as much of a factor as it is today.

At the end of World War II, Dr. Bernstein retired, and Dr. Nathan Jaret opened an office. He was a handsome, charming man and his captivating smile and his easy manner had a way of calming anyone who came to his office. Soon after opening his office, his practice was booming. As a general practitioner of that time, he delivered almost all the Baby Boomers in Middle Village. He had no problem doing house calls in those days. He was also a very enthusiastic numismatist and philatelist.

After treating his patient, he would say to the family, “Do you have any foreign coins or stamps?” And, the family, eager to please Dr. Jaret, would scurry around the house and gather their little troves and gratefully present them to him, almost as if the offering would insure good health to the family.

As Dr. Bernstein and the other medical practitioners, Dr. Jaret had limited medical equipment and depended on his diagnostic skills to keep his patients healthy.

At one point in my late adolescence, I was a bit hypochondrial. On one of my periodic visits to him, he concluded the examination by boldly stating to me, “Look, Herbert, get it through your head, no one is going to live forever, and no one is getting out of here alive.” As you can see that statement made a very definitive impact on me since I never forgot it and can still quote him word for word many decades later. If the doctor gave his patient a prescription, the next step before going home was to visit one of the five drugstores scattered around the village. Our drugstore of choice was owned by Dave Leblang, assisted by Frank Lauria. These single proprietor drugstores with soda fountains and leeches were a few steps ahead of the old apothecary shop and have virtually disappeared from the American landscape, replaced by big box stores.

In some instances, pharmacists were frustrated physicians. For whatever reason, lack of financial resources or racial and religious quotas imposed by medical schools, promising young men were shunted off to pharmacy school. Because of their frustration, whenever the opportunity arose, they would freely offer medical advice. After a few questions to rule out serious diseases, they would choose a remedy and confidently say, “Take this for a few days.” The remedy usually worked.