On May 31, 2009, I took a four-hour trolley ride through Queens with my sister. The trolley was not actually a trolley – it was a bus designed to resemble a trolley – and the ride was not a commute. The ride was, instead, a tour of famous landmarks in Queens: Jackie Robinson’s home, the apartment Jack Kerouac lived in while writing “On The Road” (and the bar where he, presumably, spent his evenings), Woodhaven Lanes, and the site of the original United Nations. This tour, envisioned and run by the Queens Historical Society, was meant to raise awareness for these historical (and often forgotten) sites throughout Queens. The fact that the tour was conducted in a trolley no doubt contributed to the general ambiance and to this larger goal, that of reminding the citizens of Queens that our borough is vast, fraught with important historical sites, and often forgotten.

The “trolley” itself was not extraordinary but the experience that it fostered was. Everything from the way that the wooden bench felt under my skin to the voice and demeanor of the driver were entirely unforgettable. From the sidewalk, though, the trolley must have appeared strange – an anomaly, a remnant from another time created for the sake of nostalgia. There was a time, however, when such a mode of traveling would not have been anomalous, when trolleys ran on our local and major roads and provided both joy and transportation. The trolleys that ran through Middle Village and Maspeth have a brief but rich history, one that left a lasting impression on those who still remember the sounds, colors, and textures of the original cars, as well as the tracks that have since been covered to make way for modernity and the new means of traveling that have followed.

The country’s first electric trolley line ran in Jamaica, Queens in December of 1887. Between 1887 and 1957, trolley lines such as the Richmond Hill line, the Flushing-Ridgewood line, the Myrtle Avenue line, the Jamaica line, and the Calvary Cemetery line (to name only a few) ran across Queens and serviced millions of passengers. In 1949, for instance, the Richmond Hill line accommodated 13,000 daily riders. The history of the trolley is not exclusive to the electric trolley, however. Before electric cars became prevalent, horse-drawn trolleys were widely used. These horse-drawn cars were smaller than their electric successors. The transition from horse-drawn cars to electric trolleys was a rocky one – the horse-drawn cars were not only smaller but also easier to maneuver through traffic because they could “jump” off of their tracks.

This lack of mobility and, consequently, element of danger, is integral to the trolley’s history and subsequent demise. They were powered by means of electric wires that

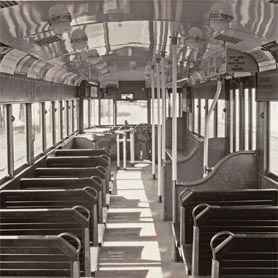

attached to their roofs; their brakes and doors were operated by air pressure. The cars themselves were perfectly symmetrical in that they could be operated from their fronts or backs depending on which direction the cars were going in. The trolleys could not “turn,” they merely switched direction. Even the chairs themselves, which were made of solid oak and situated in rows of two, could be turned around once the car itself needed to change direction. Additionally, because the cars ran on a track and could not freely deviate from that track, unlike a car, or even the horse-drawn trolleys, which could freely “jump” on and off their tracks, passengers had to be let on and off the car from the street rather than from the curb. Because the cars could not turn, accidents were often unavoidable, resulting in injuries and fatalities.

What neighborhood resident Vincent Branigan remembers most about the trolley cars, though, is not how dangerous they were, or how little mobility they had. He remembers the way he felt while riding them, the way they smelled and sounded. According to Branigan, “the trolley car really was a great way of traveling.” He stresses the trolley’s “spacious area” and “non-smelly fuel,” along with its authenticity, the inherent components of customer service, loyalty, and intimacy that seem to be missing

from today’s transportation system. Apart from the comfortable seats, the intimate riding experience, and the clean-smelling fuel, which Branigan notes “was very good for the atmosphere, for the environment,” he seems to most fondly remember the motormen and their commitment to their routes and passengers. “Very seldom if you were a steady rider would you miss a trolley,” Branigan points out, “the drivers were extremely polite… they usually knew exactly which passengers would come on at what time, especially the bingo players!” Branigan also remembers the motormen’s (who wore dark blue pants, a dark blue jacket, a blue shirt, and a dark tie) relationship to the BMT (Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit Corporation). The trolleys ran on a very strict schedule, with only several minutes of leeway. Branigan explains that it was actually preferable, however, for the motormen to arrive a few moments late rather than a few moments early, because “if you got there ahead of time, that means you were speeding.” All of Branigan’s memories of the motormen, though, come down to one simple aphorism: “he didn’t have to do it, but he did it out of courtesy.” This “it” can refer to almost anything – waiting for regular customers, trying to operate the cars safely and arrive at each stop promptly, or making change amiably.

The cars, which held up to 90 people (sitting and standing), were wider than their horse-drawn predecessors and included leather handles for standing passengers. They provided an essential service for individuals traveling both throughout the borough and into Manhattan. The ride from Queens Plaza to Second Avenue on the Queensborough Bridge trolley line took only fourteen minutes. Donald Steinmaker, another neighborhood resident, remembers this trip well. He recalls “riding all the way to Manhattan” and noticing “the guys from the Navy getting on” the car. The Queensborough Bridge trolley was actually the last running trolley line in Queens; its last ride took place on April 9, 1957, ending a forty-nine year route.

The trolleys, of course, were never strictly utilitarian. Both Steinmaker and Branigan can quickly and animatedly outline the routes that they most frequently took for pleasure. A typical trolley ride of Branigan’s would begin in Maspeth. Then, he would get a transfer at Lorimer Street in Brooklyn and transfer to the Lorimer Street car, which he would take all the way to Coney Island. This trip, which cost only 5 cents, had the added benefit of “passing the home of the Brooklyn Dodgers, Ebbets field.” Steinmaker has a somewhat similar memory of his favorite and most frequented childhood route – he “rode the Flushing-Ridgewood line to Fresh Pond Road, went all the way down into Maspeth” and then “transferred to the Flushing Line.”

Why then, if such vivid and enthusiastic memories persist, if, like Donald Steinmaker says, “it’s amazing how the trolley cars ran,” was their position as the preeminent mode of transportation through Queens eradicated so quickly? There are a variety of conspiracy theories and more reasonable explanations to explain the demise of the electric trolleys, some of which Branigan and Steinmaker openly admit. Both men own that the cars were often dangerous and unwieldy, lacking mobility and dexterity as was previously mentioned. Branigan believes that the “main reason the electric trolleys were replaced by buses…was that they couldn’t avoid an accident.” Steinmaker admits, too, that they could easily “hit you.” The transition to buses, which took place when the Manhattan and Queens Bus Corporation replaced the Manhattan and Queens Traction Company (giving up the company’s claim to a perpetual street car franchise), is addressed by both men somewhat whimsically, as if the movement to modern buses was bittersweet but ultimately necessary. Steinmaker, for instance, remembers joining the army and, when he came home, seeing that “there were buses.”

It is difficult not to imagine what Queens may have been like had the presence of the trolley persisted or, alternately, if it had never blossomed so quickly and profitably in the first place. The trolley, although now anachronistic and archaic, used primarily for historical and education purposes (like the landmark tour through Queens that I took with my sister last Spring), seems somehow relevant, too. The trolleys that were so prevalent in Queens throughout the early twentieth century were spacious, surprisingly environmentally conscious, and, according to many, a pleasure to ride. They were, undoubtedly, everything that we now strive for in our transportation systems.

Perhaps we can, by looking back at the trolley, re-imagine and rethink what transportation should be (notwithstanding the integral improvements we have made in terms of safety and speed). Whether or not the trolley, or anything resembling a trolley, makes a sudden resurgence, though, is less important than the legacy that has already been established. Riding a trolley was truly a multifaceted experience or, as Vincent Branigan puts it, the trolley did not merely provide transportation – “it was an adventure to ride a trolley car…it was terrific.”