In order to convince the City to expand the sporting facilities at Juniper Valley Park, it was clear that it would require something more than just another side-of-the-angels appeal to cleanliness, Godliness, and plenty of catcher’s mitts. The equivalent of a petition was drawn up but instead of a sea of names there were just two pages of spare, serious prose with a cover page of organizations that agreed to go on record. Additions of the Mothers’ Club of one school and the PTA of another; two different regional civic Associations, one American Legion Post, and groups with Polish & Lithuanian titles to the advocates already mentioned achieved the impression of a broad base of support. There was no reason to leave out that it was locally that Whitey Ford & Phil Rizzuto had gotten their start; and that someone had best plan for our big leaguers of the future after the closure of several local fields after the 1960 season; this compounding the departure of two N.Y. major league teams, the Dodgers & Giants, at the end of the 1957 season.

However, the clincher came from a publication, Zoning: a Proposal for a Zoning Resolution. Back in Aug. 1958 it had been prepared pursuant to government request by the firm Voorhees, Walker, Smith, & Smith, and presented to the City Planners who were now his audience. A formidable big 10” x 15” hardcover of 375 table- and map-laden pages in squint-print it was! And unlikely to have been given a detailed read by anyone. Make that, anyone else. In this arsenal of intense facts on proportions of land allowed to residential, business, manufacturing, & other uses along with how much and why this should be adjusted (re-zoned) in the future; on population density & household size per neighborhood; with re-definition into 18 “Use Groups” – on and on! Don’t bother to search your home library for a copy, bet it won’t be there.

On a certain page he cited, Harry McArdle had found statistics that supported the impression, Queens was headed for the highest population increase; opening the door to the interpretation that it would be a shabbier environment unless recreation areas – life’s important extras – were augmented. In fact, there in print was the conclusion based on data the Planning group had paid Voorhees, et.al to collect, that of all population growth up to 1975, Queens was going to account for 90%. The kind of number (whether or not time would show it to fall short of 90%) you want to have on your side when you’re asking for more. For his slim summary McArdle even invested in a folder. Its label read “APPEAL OF 112th PRECINCT YOUTH COUNCIL and AFFILIATED ORGANIZATIONS on PROJECT P-356 JUNIPER VALLEY PARK”.

This campaign was successful in getting $428,000 out of a requested 726,000 included as “Department of Parks: Additions to 1962 CBR”; instead of deferring the entire $726,000. Of course, while the rescued funds were cause for celebration, there’s always the “glass half full or half empty” model of what direction thoughts could take. $300,000 less was available, which was a lot on an early-60’s scale. (To provide comparison, a newspaper article states the then-salary of the head of the NYC Housing Authority – a big job – to have been $22,500; which is about half of what a starting teacher’s salary is today. A 1960 NYC Patrolman would have been earning around $7000 per year). We could turn to another Parks Dept. ‘Project Study’ diagram of 7-19-60 to see what adaptations to funding realities were developing. In addition to noting the major items of baseball diamonds & field house, it states “… complete walk system including sidewalks & resurface existing bituminous walks; day camp; park lighting; perimeter fencing; lawns & planting”. It is interesting to see “day camp” as there is no previous mention of one in 1960 or previous existing letters. The diagram envisions it for the spot where the original Moses blueprint had “field house” with one parking lot. It would appear this part of the plan got dropped, as cars were already congregating in two different areas – and someone’s vision of 12 picnic tables, a fountain, and B-B-Que amenities made it to paper instead. (Eventually the field house was built, but on the opposite end of the track).

The implementation of any project has its unknowns, as life elsewhere doesn’t grind to a halt. Hurricane Donna in Sept. 1960 rated as a more-than usual touch of reality. Needed attention by politicians to a 4-month newspaper strike December 1962 thru March 1963 may have slowed things a bit. By the end of 1963 it must have been hard to go forward with the same perspective, as the country was reeling from the shock of the assassination of its President, John F. Kennedy. Letters show that Juniper plans had progressed from a “promises” to a “sincere promises” to a “sincere promises with timetable” phase. The Parks Dept. went on record as expecting construction to begin in the spring; so that ballfields would be ready for neighborhood use by fall 1964. However, hearts will likely go out in compassion as we read in McArdle’s correspondence about an unexpected, we might call it “Grinch-Stealing Christmas” plot twist as to the availability of Brennan Field: “We had a permit for a soccer game on Dec. 19. When I stopped by to check the condition of the field on the Friday before, I was surprised to see a bulldozer tearing up the field and a crane digging a deep trench in the adjacent area.” A new sewer, he learned from the crew, was to run diagonally across; and this not under control of Parks, but of the Dept. of Public Works (DPW). What was that saying about the left hand not knowing what the right hand was doing?

There followed an era of meetings and new contacts with DPW – Commissioner Bradford Clark, deputies, and certain staff engineers. This could have lent itself to the ancient art of buck-passing: the contractor had already been called out as to a lax approach to compacting (roller-finish); and for coarse grades of cinder. Had the track’s fill been peanut butter, it would have been “extra crunchy”. Now this more global upset to the field’s integrity took the spotlight off cinderblock and opened the door to a game of guys waiting for the other guy to press the repair button first. There was also debate over what role normal settling of the earth played in the sub-optimal drainage situation. McArdle’s role became calling on parties to resolve their differences and calling on parties with authority to exercise it and get going. This occupied the months of 1965. (One cannot help wonder whether the City’s commitment to the World’s Fair made it a fact of life, that not everything involving construction in Queens could happen as usual).

Jan. 1966 brought with it the inauguration of a new Mayor, John Lindsay. Many of the appointees he put in place represented the fresh, idealistic qualities that were his vision during the mayoral campaign. The leadership turnover at Parks brought Thomas Hoving, who at age 34 fit the “fresh” profile, into the role of Commissioner. At first glance, given his substantial fine-arts background and recent service at the Cloisters, one might not have expected much “simpatico” with some outer borough park project. Fortunately, his interests and personal style proved to be many-sided rather than stereotyped. Nor did it hurt that McArdle had discovered at the Mayor’s Office of the Budget a person with whom he could be on a first-name basis, as another fellow 107th Infantry Veteran. The new administration was briefed on the unfulfilled promises including restoration of the track. There is a potential momentum within unfinished projects. Closure can become a goal in itself – as long as someone is out there shaking the trees and rattling the cages, so to speak. (Another side of this coin might be, beware the situation if some misconceived project gets a head start because the pros and cons are not honestly and thoroughly put on record; as finish-what-you-start has the inside track).

A reply with timetables was received stating that new baseball areas would be ready for the spring 1967 season, and by then or slightly into 1968, they were. The years brought small adaptations to the original design: for instance, field house set up at the first turn of the track rather than the backstretch end. And it serves as a point of attachment for the dedication plaque, which used to be lower on a cement base. The plaque had to be replaced once after vandalism. And the community, aggravated by after-hours activity in areas which had evolved into parking spaces, took “remove the source” action and closed them. Whether there is sufficient carrying-capacity of the park perimeter for those who need to transport children or unload sports equipment remains as one of those real-life problems of preserving the legitimate uses of a resource, in the face of a smaller but more consequential number of violations.

McArdle would likely have been pleased that support for substantial improvements to the park came in turn from both a Republican (Thomas Ognibene) and a Democrat (Elizabeth Crowley) on the City Council. By now the running lanes have been totally replaced by a synthetic ‘Mondo’ track. It is heartwarming when a project does not have to die because it is seen as the pet of one or another political party. In the Bloomberg administration there have been ribbon-cutting parties both in 2010 and 2011 to celebrate new equipment which suits the earlier levels of motor development.

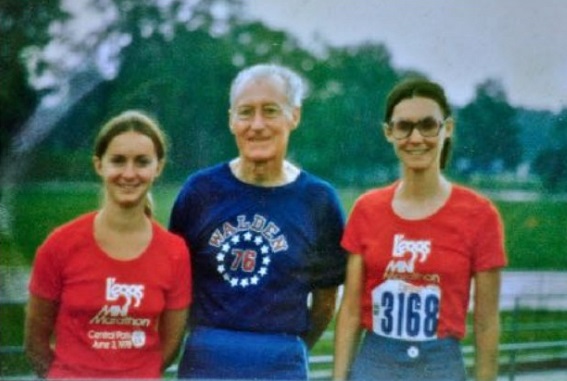

As to McArdle’s legacy – his foundation input on behalf of the Western one-third of Juniper Park – at least he got to supply a few sentences about the project as part of his life experience admissions packet for Pace University. A few sentences about all those years of his life that it took for an idea about a track at Juniper to be turned by construction into a reality. This contributed some credit – not nearly enough! -when, in his 70’s, after having seen his 3 children through to their academic degrees, he decided to earn one for himself. And at age 82 he died doing one of the things he loved, running.

*The author is the daughter of Harry McArdle