This year marks the 120th anniversary of the consolidation of Queens, Kings, New York and Richmond counties into Greater New York. As December 31st, 1897 flowed into January 1st of 1898 New York City assumed the boundaries of what it is today. However, Bronx County became New York City’s fifth county, or borough as we like to say, in 1914 after being carved from New York County. It was the 62nd and last county of New York State.

The concept of an ‘Imperial City’ had been in the thoughts of politicians for almost a century. The great planners and thinkers of those times wanted a vastness that would rival and surpass London, Paris and other European cities. A celebration in Manhattan took place in the dark and cold rain on New Year’s morning in 1898 and was sparsely attended. Many citizens of the new city were apprehensive about the marriage of their counties. Authorities decided to hold a several-day gala they called ‘Charter Day’ in May of that year commemorating the city’s new charter and that, too, was a ho-hum affair.

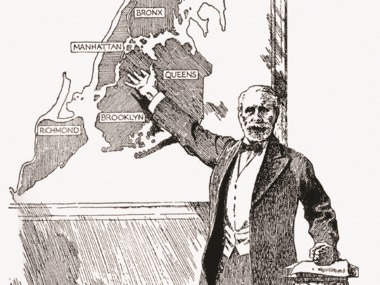

New York City had always been the island of Manhattan and several smaller surrounding isles that stuck out of Upper New York Bay and the East River. In 1868, Andrew H. Green, a doer and shaker who headed the Central Park Commission and was a city planner, proposed the annexation of parts of the Bronx and eventually parts of Kings, Queens and Richmond into its fold. Boss Tweed did not take kindly to the idea and killed it. Two years later, Tweed was relegated to history’s junk pile due to corruption and Green was named City Comptroller. In this capacity, he straightened out the city’s finances, ended graft and stopped thievery from the treasury. He used his personal credit to pay municipal employees and avert bankruptcy. He is one of the unsung heroes of New York.

Over the next decade, Green and his fellow planners and dreamers continued their quest. Political squabbles and party bickering, parochial territorial views, inevitable changes in leadership, fear of becoming a second city, stalling of population growth and financial recessions all played roles in slowing the path to New York becoming an ‘Imperial City’. In the early 1890s, consolidation seemed to be at hand only to have the City of Brooklyn politicians kill the proposal in Albany. However, Green would not stand for it. He had a bill introduced in 1894 that called for a yay or nay vote and the legislation passed and was signed by the governor. In November of that year, the referendum went to the voters. All of the counties approved with only Flushing in our home county rejecting the notion.

But dissent was brewing in Brooklyn. A group calling themselves “The League of Loyal Citizens” with a membership of about 50,000 whipped up negative sentiment against consolidation. They lobbied Albany and managed to have the referendum overturned. Enter Thomas Platt boss of the Republican Party. Recognizing that consolidation would increase his power, he revived the bill and rammed it through Albany in 1896. Consolidation would officially take place on January 1, 1898.

Greater New York was now a fact and it mirrored the geographical area conceived by Andrew Green. Over a quarter of a century later, Green’s dream came to fruition.

Our section of Queens was not immediately affected by consolidation. The full effects would not be felt for about twenty-five years. Prior to the amalgamation of our now borough, technological progress was appearing. Electric trolleys debuted in 1894 and were slowly replacing those powered by horses and steam dummies. Some homes had electric light replacing gas mantels, oil lamps and candles. Indoor plumbing was the rage with the introduction of piped water and sewers. Soon, outhouses were out and well water was used only for gardening, cleaning and clothes washing. I can remember some old Middle Village structures that still had pumps and remnants of outhouses back when I was a boy. A huge upgrade to our local thoroughfares was the paving of roads. Prior to paving, most of the ancillary roads consisted of compacted dirt. After rainstorms, these rutted roads became rivers of mud, and the rain also caused the flooding of basements, barns, garages and sheds. The addition of sewers mostly alleviated this problem.

Middle Village, Glendale and parts of Ridgewood and Maspeth were still pastoral. Industry had crept into Maspeth and Ridgewood along the Newtown Creek in the mid-19th century. Various corporations flocked to the creek for the transportation benefits it provided for delivering product to the city, nation and world. The Rural Cemetery Act of 1847 transformed much of our immediate area from farms to burial grounds. Being prescient, and running out of burial space in Manhattan, the Archdiocese of New York in 1845 purchased several farms located in western Maspeth and opened Calvary Cemetery for this purpose in 1848. In 1849, the Cemetery of the Evergreens was formed followed by Mount Olivet in 1850, Lutheran (now All Faiths) in 1852, Cypress Hill National Cemetery in 1862, St. John in 1879 and Mt. Zion in 1893. Many other cemeteries were established along the terminal moraine in Glendale and Ridgewood because the land was hardscrabble and relatively cheap. At present, Queens County contains about 2,000 acres of cemetery containing millions of the deceased.

Business relating to cemeteries exploded during the mid to late 1800s; florists, gardeners, monument manufacturers, stone cutters, hotels, restaurants, livery stables abounded. The cemeteries ringed the neighborhood and land developers found it much easier to purchase farms outside the area on which to build homes and apartments. The smaller farms of the area survived into the first two decades of the twentieth century. In addition, many developers were convinced that customers would steer clear of homes by burial grounds.

One of the last vestiges of the old towns was the Volunteer Fire Departments. Many of the departments of our locale were last to be disbanded by the FDNY. The Middle Village Fearless Company, The Metropolitans, The Maspeth house and the Ivanhoe in Glendale all existed for many years and protected their neighbors from deadly fires which occurred with regularity. They met their demise in and about 1913. Those who read this magazine are sure to recall the articles about the volunteer departments of which many of our ancestors were members.

The opening of the Williamsburg Bridge in 1903 and the Queensboro Bridge in 1909 brought explosive new growth to our area and its surrounds. Metropolitan Avenue led from the bridge into the heart of our neighborhood and Queens Boulevard provided entrance to the area via 51st/Maurice Avenues, 58th Street, 69th Street, Grand/Flushing Avenues and Woodhaven Boulevard. Progress inevitably followed. During this time, automobiles were becoming popular and affordable. Thoroughfares such as Northern Boulevard, originally an Indian trail, and Queens Boulevard, formerly Hoffman Boulevard and Thompson Avenue, were providing access to the eastern points of the borough. They proved to be so popular and direct for drivers that they eventually were expanded into their current width. Woodhaven Boulevard, formerly Trotting Course Lane, which began in the 1660s as a route to Jamaica Bay and the Atlantic Ocean was widened in the early 1900s.

Mass transportation was also increasing with the extension of the Myrtle Avenue elevated line. Until 1908 the ‘el’ went along Myrtle Avenue to Wyckoff and Myrtle Avenues terminus. The ‘el’ was extended to Metropolitan Avenue in 1915. In 1916 the Flushing line began its long trip east, which began in the late 1800s, eventually reaching Main Street in 1928. Also in 1928, the 14th Street/Canarsie line began operation into Manhattan. Both lines allowed locals easier access to the ‘city’.

Progress seemed to be passing by eastern Maspeth, Glendale, Ridgewood and Middle Village which were still countrylike for a short time. With the price of real estate booming and no need to add more cemetery space, the great farms and picnic parks of area were soon to meet their demise. The old timers were passing on and their children acceded to the financial incentives of the developer. The Wyckoff, Meyerrose, Way, de Bevoise, Nurge, Lott, Van Sise, and Vanderveer farms and more disappeared from the local landscape to be replaced by a panoply of edifices; one, two, three, four, six, eight family homes and some even larger apartment buildings. It is estimated that over 100,000 homes were erected in Queens between 1900 and 1925. During this time, many of these homes were built in our area.

World War One did not have much of an impact on Middle Village and the immediate area. One of the men we lost was Joseph B. Garity. The American Legion Garity Post is named for him. This Post was founded in the Bowden Blacksmith Shop which was located at Metropolitan Avenue and 62nd Street. In 1950, after the Second World War, the Post erected their structure at Fairview Avenue and Madison Street. In years past the Post sponsored various youth programs and local events for veterans. In recent years the post moved to a building on Myrtle Avenue in Glendale.

By the late 1920s there were few open spaces left in the neighborhood. There were what we referred to as ‘lots’ consisting of several blocks of open space but not much more. Middle Village east of the Eliot Avenue cut though at Mount Olivet and All Faiths Cemeteries had some of the last open spaces where kids could run, play ball, see frogs and turtles, rabbits and pheasant.

It took a while for our area to catch up with the growth of much of Queens post consolidation. We were a pocket of tranquility encircled by the bustle of a growing urban sprawl. Eventually, the developers rediscovered Middle Village and the surrounding neighborhoods and gobbled up the last open spaces for much needed homes for the growing families of veterans and immigrants. But you will notice as you wander about our neighborhood, it still maintains not a pastoral but a small-town aura that is missing elsewhere in the ‘Imperial City’.