I heard the front door open and close, followed by heavy footsteps, ascending the creaky stairs that lead to our apartment. I ran to the door following the knocking. When I opened the door, there was our insurance man, Mr. Leibowitz. He gently patted the top of my head and asked if my mother was at home. I cried out “Momma, Mr. Leibowitz is here!”

After she breathed a sigh of relief that it wasn’t the inspector from the Labor Department, she placed the ties that she was sewing on the cot and walked to the kitchen. I didn’t pay attention to their conversation, but I scrutinized and studied Mr. Leibowitz from head to toe.

As a fatherless little boy, I had an affinity for any older male. Mr. Leibowitz was quite different from the men that came to daven in the little shtiebel that my father and uncle Hymie had built up the block from our house. First, to my naïve young mind, he resembled our president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, because as Roosevelt, he was balding, and wore rimless eyeglasses. As a matter of fact, to me any man who wore rimless eyeglasses, ergo, Mr. Hartwig, the principal of PS 87 and Mr. Himmelstein, president of the Middle Village Credit Union were clones of FDR.

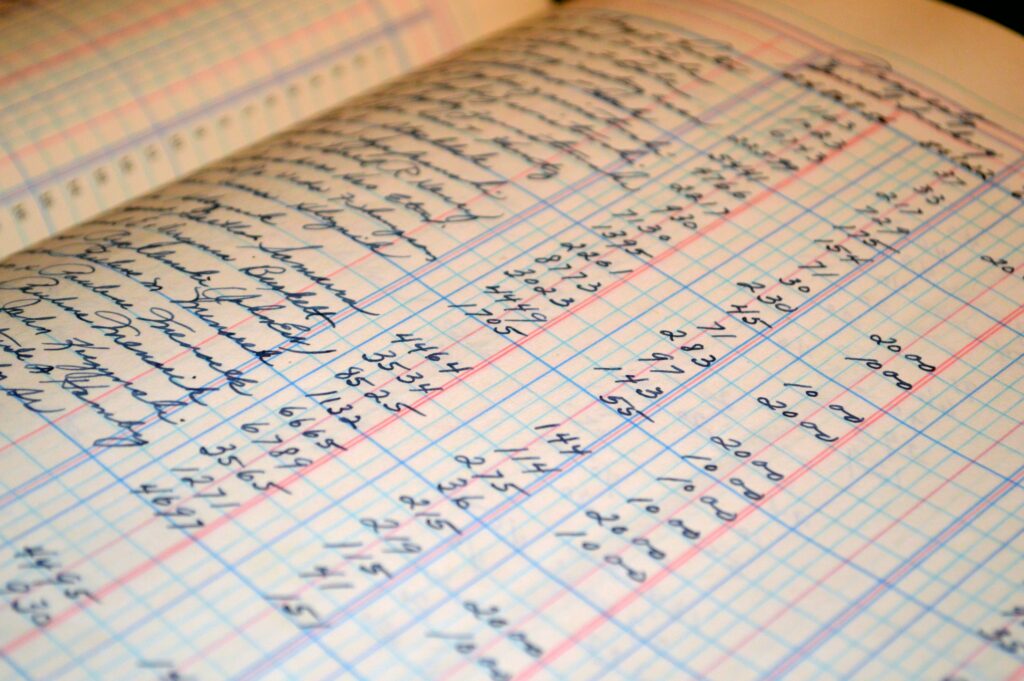

Mr. Leibowitz, compared to the men of the shtiebel, was regal. He was well shaved, wore a neatly pressed suit with a vest, and tie, and I noticed his brilliantly shined shoes. It was an enigma to me that this apparently important man would be sitting at our kitchen table engaged in serious conversation with my mother. To top it off, on the floor next to him was an impressive, large briefcase, from which he extracted a huge ledger. This looked to me like a telephone directory. He laid it on the table, opening to a particular page. At this point, my mother walked hastily to her bedroom and returned with a small book, which I know she kept in her dresser drawer. She sat down in her chair and handed him her little book, along with some small change; the amount of which I never noticed. Then, with almost a flourish, he reached into his suit jacket breast pocket extracting his pen. I watched as he carefully uncapped the pen. Compared to the simple wooden penholder with a steel nib that I used in Mrs. Hauptman’s classroom, his gold nibbed Waterman pen looked like a very official instrument. He made an entry into the giant ledger and then made a notation in my mother’s little book. He produced an ink blotter, and carefully pressed it to the pages. This gesture reminded me of a scene in the movie that I had seen in the Arion Theater, in which some Royal had pressed his signet ring into melted wax on some important document. As soon as he was certain that the ink was dry, he deftly capped the pen, placed it back in his pocket, and handed the little book back to my mother.

This little ceremony reminded me of seeing the authoritarian General Douglas MacArthur end World War II, by proclaiming, “These proceedings are now closed!”

At this point, Mr. Leibowitz seemed to relax and began to engage my mother in conversation. What they talked about I do not know. In retrospect, it seems to me that he was playing the role of a minor noble giving an audience to one of his serfs. After a few minutes, he rose, picked up his briefcase, bid his goodbyes and departed. He apparently went up the block to see his next client where the same scene was repeated until all his appointed rounds were completed for the day.

The point to all this that is my perception as a youngster, was that all was well with the world. The war had ended, my brothers would be coming home soon, and we would all be together again. Once again, “These proceedings were now closed!”

A footnote: although I imbued Mr. Leibowitz to be lordly, he was a schlepper, a small insurance agent, who went house to house, collecting small change for life insurance policies. He probably made a living but was not the wheeler-dealer I imagined him to be.

The most ironic part of my tale, unbeknownst to me, is that when my mother died, I was the beneficiary of the policy. I received a check for $10,000! I could never bear to spend one penny of that money, knowing the sacrifices she made to ensure that I would never be without. Thank you, momma, you selfless woman!