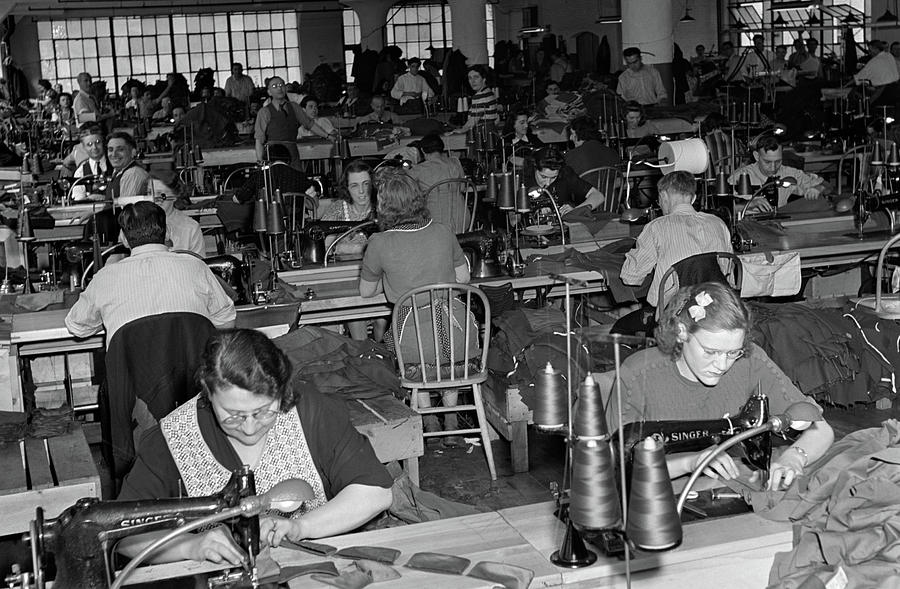

Momma worked in a shop hand sewing men’s neckwear. She was given a bundle of pre-cut fabric from which each piece was removed and placed on a table. A gauze lining was put in place and on top of that a flat piece of cardboard shaped like a tie. The item was then pinned, the cardboard removed, and the tie hand sewn. The work was difficult on one’s hands and eyes, repetitive and with loose gauze threads clinging to one’s hair and clothing. Most noxious of all was the fact it was piece work. That meant the amount of money earned each week, minimal at best by today’s standards, depended upon the quantity of finished ties produced.

Implicit in this type of earning arrangement, was hurrying through the lunch brought from home, avoiding going to the bathroom until it was absolutely necessary and talk among coworkers kept to a minimum. It was dreary and unpleasant compounded by a long and crowded subway ride home requiring two or three changes. The last stop was the BMT Metropolitan Avenue El Station and often to save five cents, Momma walked from the station rather than take the trolley.

Once home, Momma cooked dinner for Pappa and her five children, did the laundry (by hand -no washing machine) which was then placed on the backyard clothesline to dry. To make ends meet (home relief was something unacceptable to us) Momma also sewed ties at home. We would pick up bundles of pre-cut fabric in a shop on Allen Street in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, and at night, after dinner and the other chores completed, we would pin the ties. Momma then sewed them, often working late into the night. This sewing was also on a piece work basis. Occasionally Momma moved the clock back so Pappa wouldn’t know how late it was.

When the ties were returned to Allen Street or perhaps the shop owner picked them up, a count was made and the amount to be paid determined. This was commonly known as homework. It was illegal and New York City Department of Labor agents were constantly on the prowl to locate houses where the work was being done. If caught the ties were confiscated and the work done for naught. We were always in fear of the sudden knock on the door and the appearance of the agent. Often upon hearing a knock, the ties would quickly be thrown into a closet, the door opened, only to be met by a neighbor or relative.

Notwithstanding the enormous physical labor Momma was obliged to do, I never once heard her complain. She did occasionally acknowledge with gratitude the Shabbos she observed as truly giving her a day of rest.

At the shop where Momma worked days, each bundle of fabric had attached to it a two-part numbered ticket. When a bundle was completed, the worker removed one part of the ticket and kept it as evidence of the work done. On Sunday Momma gave me all the tickets for the previous week and a small lined notebook which had her name on the cover. It was my job to record in columns all the ticket numbers. On Monday Momma would give the shop bookkeeper the book and the tickets. She would then verify them against her tickets, make a tally and determine what was earned. It took me about 30 minutes to make and complete the entries in Momma’s book.

I must have been twelve years old at the time and not very sensitive or smart and oblivious to how hard Momma worked. Indeed, I was annoyed with the bookkeeper in Momma’s shop and could not understand why it was not she who recorded the tickets. In retrospect this was absurd because there were dozens of women in the shop and it would not be possible for the bookkeeper to record all their numbers. Furthermore, by keeping their part of the tickets, the workers were assured of an accurate count. In my naiveté I did not realize any of this, so one week I slipped a note in Momma’s book addressed to the bookkeeper complaining about my having to record all these numbers and questioned why she wasn’t doing it.

The following week when Momma gave me her book there was a note in it for me from the bookkeeper. She acknowledged my letter and in a scolding tone informed me that Momma worked in a filthy shop under terrible conditions, rushing to complete as many ties as she could and then rushing home to cook, clean and care for her family. How dare I, she wrote, complain about having to spend about half an hour a week to help my mother and that I should be ashamed of myself. She was, of course, right. Her letter fell on me like a ton of bricks making me realize immediately how selfish and foolish I was.

I am forever grateful to Momma and that bookkeeper for indelibly printing in my mind the importance of a work ethic and that it was to be respected, appreciated and admired. Nor did I ever forget that Momma’s efforts were never to be taken for granted and that life’s book of accounts must always be balanced.