If a young fan first started watching New York Yankees baseball around 1996 – when he or she would have been about seven years old – and if that fan goes on to live a long life – then the voice of Philip Francis Rizzuto might still be playing in his or her mind into the 2080s – some 140 years after his debut as a player.

“Holy cow,” the Scooter would say. We can hear it now.

His was the voice that first taught you the rules of the game, the love of the game, the characters (“huckleberries”) of the game, and first introduced you to Roger Maris, Bobby Murcer, Thurman Munson, Ron Guidry, Don Mattingly, Derek Jeter, Mariano Rivera and so many more.

The author, Marty Appel, and Phil Rizzuto

For 56 years, he was top of mind in New York and its environs. The kid shortstop from 64th Street and 78th Avenue in Glendale, Queens and Richmond Hill High School, had broken into the starting lineup with his hometown Yankees in 1941, replacing the popular Frank Crosetti at shortstop. He went on to play in nine World Series and five All-Star Games and was there when television discovered baseball in the late ‘40s. That was heady stuff for the son of a trolley motorman from “the old country,” Calabria, Italy.

He got 200 hits and won the American League Most Valuable Player Award in 1950 (after finishing second in ’49), and was teammates with no less than Joe DiMaggio, Mickey Mantle, Yogi Berra, Tommy Henrich, Bill Dickey, Red Ruffing, Lefty Gomez, Whitey Ford, Billy Martin, Elston Howard, Allie Reynolds, Vic Raschi, Eddie Lopat, Charlie Keller, Joe Gordon, Snuffy Stirnweiss, Joe Page and so many more players who were household names, certainly around New York City.

DiMaggio was especially magical to him. “I used to like to watch him shave!” said Phil, appreciating all that was around.

Illustrations by John Pennisi

As a player he made his own mark. He was one of the best bunters in the game’s history, and one of the best fielding shortstops who ever played that important position.

“I’ll tell you what,” said Ted Williams. “If we had him in Boston, we would have won all those pennants, not the Yankees!”

He would stick his bubble gum on top of his cap when he came to bat. He had his superstitions and rituals and his teammates enjoyed them all, because he was first and foremost, a tough player – a “gamer” – who was never going to let his 5’6” frame be a disadvantage. It’s what he learned playing stickball in Queens, football in high school, or when he was told at a New York Giants tryout, “Go get a shoeshine box, kid.” He wasn’t about to be denied.

He played for three Hall of Fame managers – Joe McCarthy, Bucky Harris and Casey Stengel, and had he not missed three seasons for Navy service in the Pacific during World War II (“I was seasick every day”), there is no telling how much more his career might have realized.

Ah, the Navy. When the broadcast booth was reconfigured at Yankee Stadium, there was a ladder, flat against the wall, that one had to descend for entry. Rizzuto watched several people gingerly make the attempt and then said, “You huckleberries, this is how you do it in the Navy.” And 1-2-3 he scooted down the ladder. He was in his 70s.

He was honored with a Phil Rizzuto Day at Yankee Stadium more than once, but is remembered for the one in 1985 on the day that visiting player Tom Seaver won his 300th game. On that day a cow (a “holy cow” being presented by the Daily News), stepped on Phil’s foot knocking him over.

He has a plaque in Monument Park at Yankee Stadium and his number 10 is retired. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1994.

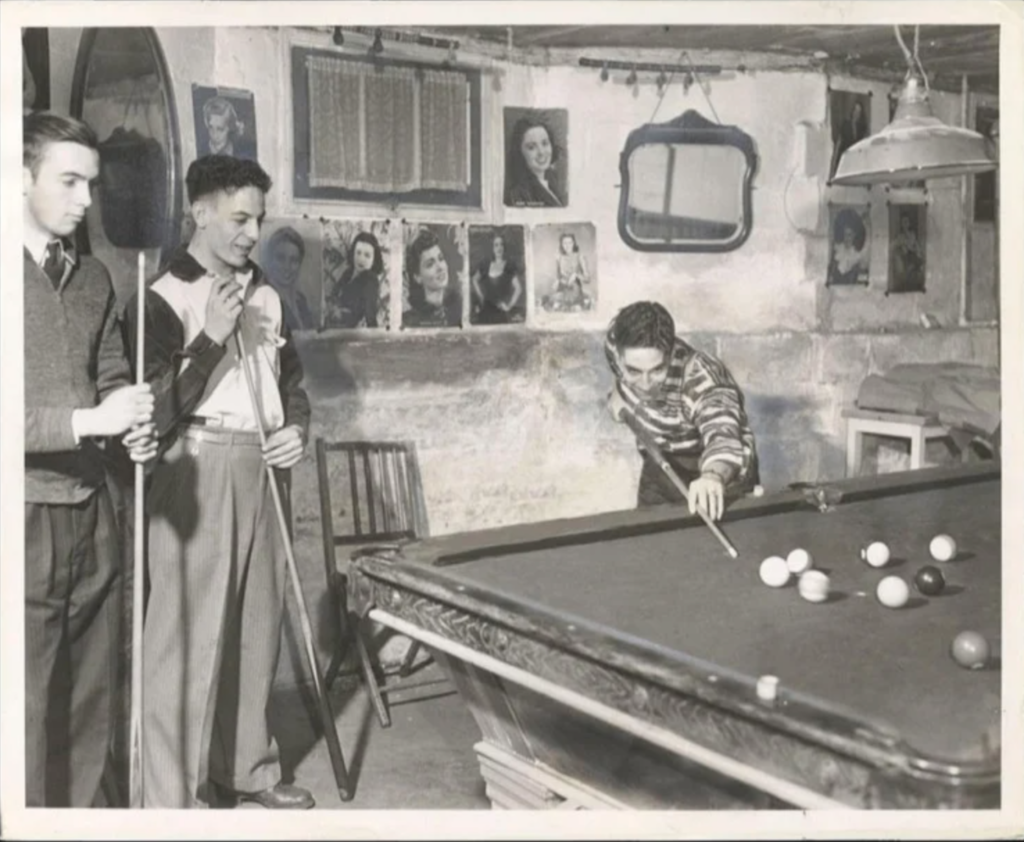

The home where Scooter grew up in Liberty Park, Glendale

When his playing career ended in 1956 at age 38, he soon became part of the Yankees broadcast team, joining the legendary Mel Allen and Red Barber in the broadcast booth for both television and radio. It was intimidating – Allen was accommodating but Barber hated working with former players. And so Phil would remind himself that he had broken in as a player in an even more intimidating setting, looking around the tiny clubhouse at names he had been rooting for from a bleacher seat, just a few years earlier.

With his ability to make friends among teammates, the press, fans, and the business community, Phil’s popularity quickly soared in New York. He made countless banquet appearances, owned a bowling alley in Clifton, New Jersey with his buddy Yogi, signed a big endorsement contract with The Money Store (a lending company), and converted his friendships with the advertising people from Ballantine Beer into a 40-year broadcasting career. (He also did daily reports on the CBS Radio Network for many years). He met his wife, Cora, who he would make famous on his broadcasts, at a communion breakfast, pinch-hitting for DiMaggio who asked him to attend in his place.

Phil’s development as a broadcaster was held back a bit by the overshadowing presence of Allen and Barber, but if you hear his call of Roger Maris’s 61st home run in 1961 (it’s on YouTube), you can already hear the enthusiasm and excitement Yankee fans came to love. By 1964 he was chosen over Mel Allen to call the World Series on NBC, and by 1967, he was the senior man in the Yankees booth, going on to team with a host of broadcast partners including Joe Garagiola, Frank Messer, Bill White, Jerry Coleman, Bobby Murcer, Fran Healy, Tom Seaver, Spencer Ross, and even a young Michael Kay.

People used to say, “Oh, I love Rizzuto and White,” or “I love Rizzuto and Healy,” or “I love Rizzuto and Murcer,” and you know what? – there was a common denominator to all of that. And it was Rizzuto. He just made everyone he worked with comfortable and brought out the best in them all. He brought no ego with him into the booth.

Rizzuto plays pool in the basement of his Glendale home while his friend and brother watch

At the same time, he became a total professional in his field. He could read advertising or promotion copy, pre-tape game introductions, and lead into commercials as well as anyone.

He had his quirks. He hated bugs, he hated snakes, he hated lightning, and he sometimes liked to leave the game early to beat the traffic. He liked to call out birthdays or restaurants that he frequented, and would write “WW” in his scorebook for plays he missed. (“Wasn’t watching.”) As a broadcaster it was important that he do play-by-play, lest he be distracted by visitors to the broadcast booth who thought nothing of interrupting his work while he was on the air.

He was sensitive to the changing styles of American life. One year, when I was executive producer of the telecasts, I got a call from a woman who identified herself as a 60-year-old Chinese American. She noted, politely, that Phil’s habit of calling home runs that just cleared the wall “Chinese home runs” was insulting, suggesting they were inferior to “real” home runs. She had a good point. I discussed it with Phil and the term vanished from his vocabulary. He didn’t have to be reminded; he never did it again. He got it.

When his playing career ended in 1956 at age 38, he soon became part of the Yankees broadcast team, joining the legendary Mel Allen and Red Barber in the broadcast booth for both television and radio. It was intimidating…

He and Cora, and his children Patty, Penny, Cindy and Phil Jr., (only Penny survives), lived in New Jersey for much of his adult life, but Scooter never forgot where he came from, and would happily recall his days playing sandlot or high school baseball in Queens.

His Hall of Fame induction speech (also on YouTube) remains one of the most memorable ever delivered in Cooperstown. (“Holy cow, I didn’t even get to my broad- casting career!”)

Also memorable was the use of his voice in Meatloaf’s “Paradise by the Dashboard Light,” for which he received a Gold Record. A documentary about his life, narrated by Charles Durning, received an Emmy nomination. At a 2006 auction, his MVP award was sold for $175,000.

His closing remarks in Cooperstown were “I want to thank all of you who have been there for the most wonderful lifetime one man can possibly have, and I want to say God bless this wonderful game they call baseball.”

Phil died peacefully in his sleep at 89 on August 13, 2007 – having lived a life he could barely have dreamed of growing up in the section of Glendale known as Liberty Park.

To which we can all add an approving, “Holy cow!”

Marty Appel, a former Maspeth resident, has had a long Yankee-related career as the team’s PR Director, TV producer (Rizzuto’s boss), and historian. He is the author of 24 books including Pinstripe Empire, Casey Stengel and Munson. He was captain of the AAA School Safety Patrol at P.S. 78 in 1959-60.

Join in on the fun Sunday, June 26 at 2pm as Scooter’s street sign is unveiled at 78th Ave & 64th St in Glendale. (Yes, there will be cannoli!)