We are just a short time past the seventy-fifth anniversary remembrance of the December 7th, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor “…a date which will live in infamy”. This act of terrorism ushered our nation into World War Two and young men and women rushed to defend and serve America in its time of need. Patriotism was on the rise in this country as it climbed out from a devastating financial depression.

Those who could not join the military found other means to express their fealty to the cause. Young girls and boys collected scrap metal, used tires, glass and newspapers of which there were many more than today. Those too old for that work performed as air raid wardens, auxiliary firemen, hospital and school volunteers. A sleeping giant had been awoken.

Other displays of support were parades, fund raisers for the USO, billboard ads and monuments. To this day, many of these monuments dedicated to those who served and survived and those who made the ultimate sacrifice exist in Middle Village, Maspeth, Ridgewood and Glendale.

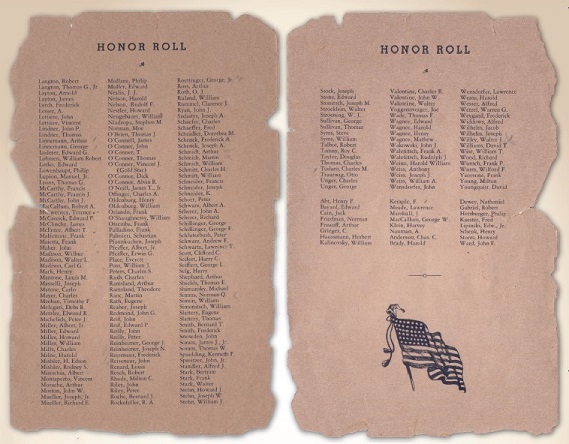

One of these monuments is now among the missing in action. In 1942, the Metro-Fresh Pond Honor Roll Committee was formed to celebrate those serving our country. Many of the area leaders and merchants lent their time to this endeavor including Andrew Todaro, Al Normandie, Joe Wunderlin, Karl Purcer and more.

The committee decided to erect a Service Plaque near the intersection of Metropolitan Avenue and Fresh Pond Road. They chose artist James Villani to portray the four groups of our fighting men. This plaque would be temporary and a monument would replace it at war’s end with the names of those who gave their lives carved into the granite for eternity.

The Service Plaque was dedicated on Sunday, December 27th, 1942 at 62-12 Fresh Pond Road. This site was on Long Island Rail Road Property and they graciously granted the Committee’s request for placement there. A lengthy ceremony was held on this winter’s day replete with patriotic addresses, the Pledge of Allegiance, various prayers and music provided by the P.S. 153 band.

When the war was won the committee hired John Lux, a stone cutter of local repute, to manufacture the monument. The committee then undertook the task of finding a permanent site for the monument. Unfortunately, this task proved to be extraordinarily difficult and frustrating.

The Long Island Railroad decided that a permanent monument on their property would be impossible due to the fact that it would be erected on a bridge over their tracks. A search for a secondary place proved problematic – no one wanted to donate or sell a small portion of retail property on Fresh Pond Road or Metropolitan Avenue on which the stone would reside.

As time slipped away and monument placement took a backseat to ordinary life, the effort to find a home faded.

When the monument was completed Mr. Lux asked the committee where they would like it to be delivered. They did not know. Finally Karl Purcer, proprietor of Karl’s “Dee Old Homestead”, told the committee that he would allow the monument to be erected in the corner of his triangular property which bordered Fresh Pond Road and the Long Island Railroad. “Ach”, he said in a heavy German accent, ”The boys all drink here and this country took me in. Put it here.”

The Committee was relieved to have finally found a home for their edifice and Karl was happy to have it. His generosity was not totally altruistic, it was good for business.

The monument was placed with no fanfare sometime in 1946 and remained there for years through many a picnics and parties in his outdoor beer garden.

In the early 1950’s many of the servicemen were married with families and moving to suburban homes on Long Island. The picnics in the garden became fewer and the monument disposed to the back of many minds since it was located on private and not public property.

Over the years the granite became stained and hidden by ailanthus trees and weeds. When Stanley Schayne became the manager of “Dee Old Homestead” he took on the project of exposing and cleaning the monument exposing it to past glory and honor. Not long after, an auto backed into the monument causing a large piece of granite to be broken off. This was the beginning of the end. No one wanted to repair or replace it so it stood in the corner gathering weeds, dirt, dust, and pigeon droppings.

As a boy I lived a couple of blocks away from the Homestead and played on the railroad tracks. My friend and I used to enter the tracks off Metropolitan Avenue and play on the pedestrian trestle and the cinder paths surrounding the tracks. We would stand on the trestle and jump onto moving coal and sand cars riding them until they slowed by Grandview dairy or the old Welbilt stove factory. We’d then “tightrope”-walk the tracks back to Fresh Pond station. When there were riders or workmen on the tracks we’d maneuver up the side of the cutout by the Homestead and climb over the chain-link fence, resting our feet on the now unrecognizable monument before exiting the old picnic area which was then relegated to a parking lot.

During snow storms in the mid to late 1960’s I used to shovel the snow in front of the Homestead for Mr. Purcer and the monument, or what was left of it, sat forlornly in the corner losing chips and chunks of granite.

After Mr. Purcer passed away I was no longer needed to shovel. The Homestead passed through several new owners eventually becoming a “Wienerwald, a Chinese restaurant, a disco, a Ford dealership and more. It is now a tanning salon.

The property in the area also changed to the point that it is no longer recognizable. The Long Island Railroad built a platform over part of their cutaway allowing Meyer Chevrolet to expand their dealership. After Billy Meyer passed away the dealership fell on hard times and now a CVS occupies the location.

I am under the opinion that the monument was a casualty of the change of Homestead ownership or the building of the platform. It could be buried under the platform in years of garbage along the cutaway or it may have ended up as crushed rock in someone’s driveway. I doubt we will ever know.

What I do know is that it is a lost monument to those who served and those who gave their lives in World War Two.