As we near the end of the year marking the 75th Anniversary of the end of World War II, we’re reminded of the fact that it won’t be long before the last of the World War II Veterans are gone, but hopefully not forgotten. I unfortunately have experienced the regret of not talking more to my godfather, Robert J. Aitchison, about his experiences in that horrific war, and he died just a year short of seeing the 75th anniversary of his part in that great endeavor. But his story is worth telling even if he himself didn’t speak much of his experiences for over seventy years. Only in the last year of his life, in talking to my mother, did he start to mention the names of the other men he served with who, like him, were really just boys. So, what I do know has been told to me by my mother, his sister Gladys, who although was only five years old when he enlisted in 1944, would not forget the most important details of his story, the details that could not be hidden from others, as you will soon find out. Much of the other information and details about his time aboard the air craft carrier USS San Jacinto I was able to find from the U.S. Navy Cruise Books available in print and online, as well as the copy of his Distinguished Flying Cross papers, which can be found as part of “The Wall of Valor Project” on militarytimes.com.

My Uncle Bob, born in 1926, tried to join the Navy before his 18th birthday, while he was still attending Thomas Edison High School in Jamaica, Queens. Being underage, my mother remembers their mother crying over the signing of his enlistment papers, which she did not want to do, but I suppose he reasoned with her that he would be 18 soon enough so she signed them under much despair. I’d imagine we’d have to put ourselves into the minds of the boys and young men who lived during this time in order to understand why one would sign up to be sent overseas to fight in a war in which so many young men who’d gone before them died. My Uncle Bob was already 14 when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, so that might have had something to do with his decision to go. After basic training in Jacksonville Florida, the muster roll papers I found on Fold3.com put him in San Diego, California on August 3, 1944, less than 4 months after his 18th birthday, where he would be taken by naval destroyer to Guam, where he would then board the USS San Jacinto, named for the 1836 battle for Texas’ independence from Mexico, and led by General Sam Houston.

According to the U.S. Navy Cruise Book which covers the years 1943-1945, I learned that he was part of air group FORTY-FIVE and that they embarked on 30 November 1944. His rank according to his Distinguished Flying Cross was Aviation Radioman Third Class, but he was also the tail gunner in his flights in combat. The San Jacinto rendezvoused with other units of the Fast Carrier Task Force off the Caroline Islands in the Pacific Ocean where they had a week of intensive training, and on 11 December they set course for the vicinity of Eastern Luzon, the largest of the Philippine Islands, to capture the Philippine island of Mindoro. Heavy weather and high seas seriously hampered operations but their fighter planes flew sweeps against the airfields. They encountered no air borne enemy planes, but they destroyed 3 grounded aircraft, and some buildings and runways. Perhaps due to the heavy weather two fighters failed to return and their pilots were declared missing in action. Those pilots are named in the Cruise Book. Another fighter had to make a water landing and two more crashed into the barriers, but personnel on board these fighters were unharmed.

This was just the first of many much more dangerous missions the San Jacinto would be part of and when I realized how intense things got for my uncle and the San Jacinto almost from the start of his time and commission on board. On 17 December they tried to refuel near Luzon, but the heavy seas and adverse weather forced all refueling and flight operations to cease. By dawn of the 18th, “the Task Force and Logistic Units were fighting their way through one of the most severe typhoons ever to be encountered and survived by naval units in the Pacific, with many ships suffering varying degrees of damage and three destroyers being lost. The San Jacinto suffered severe but not crippling damage when the excessive rolling and pitching (42 degrees) caused a plane on the hangar deck to loosen and snap its heavily reinforced mooring lines. The runaway smashed into other parked aircraft, loosening them in turn, and in short order the hangar deck was a sliding mass of planes, engines, tractors and other heavy equipment which was smashed from side to side. Small fires which broke out were quickly extinguished and by the valiant efforts of repair parties and volunteers and the hangar deck was secured by 1600. The storm gradually abated during the afternoon and repairs were commenced immediately.” Much of the repairs were accomplished en route the Caroline Islands where the ship would moor from 22 to 27 December to complete repairs and spend a very thankful Christmas “with religious observances and a mammoth turkey dinner”.

This sounds like the end of the story but anyone who has lived through the perils of World War II knows it was just the beginning. The San Jacinto continued its attacks on the Philippines and Formosa (Taiwan), amidst adverse weather in January 1945, and in support of MacArthur’s troops. It should be mentioned that Former President George H.W. Bush was on the San Jacinto as part of torpedo air group 51, from spring until late fall of 1944. Air Group Forty-Five was at first part of Task Force 38, which 4-Star Admiral John S. McCain, Sr. commanded. His son John S. McCain, Jr., also a 4-Star Admiral, commanded two submarines in the Pacific, who is the father of late Senator and Vietnam Veteran John S. McCain III. Later the San Jacinto was part of Task Force 58, where in February they began their attack on Iwo Jima and Tokyo, somewhat a revenge mission for “the treachery of Pearl Harbor”. They continued their attacks on the islands of Japan, and by mid-March of 1945, “the American Forces were seizing a part of the Empire itself. Okinawa was the strategic key to the whole Pacific tactical situation. Japanese resistance was determined and fantastic and for a while the Navy’s price in casualties exceeded that of the Army and Marine Corps combined.” The San Jacinto and the entire fleet of Task force 58 spent nearly 4 months dodging Kamikaze and Japanese suicide bombers, many of which were shot out of the sky by our gunners. Some, of course, hit their targets and there is a YouTube video of the San Jacinto narrowly escaping serious damage from a Japanese suicide bomber on April 6, 1945. She also saw the Intrepid grazed by one on March 18, 1945.

The San Jacinto’s Torpedo Bombers and Hellcat Fighters flew mission after mission and many crashed, were shot down, and made emergency water landings. Some of the pilots and crew were recovered, many went missing in action and still more were lost at sea. My Uncle’s plane was shot down sometime on or before April 5 because his Flying Cross award says, “As radioman and tail gunner of a carrier-based torpedo plane during the period 3 January to 5 April he participated in twenty air strikes against enemy shipping, airfields and installations.”

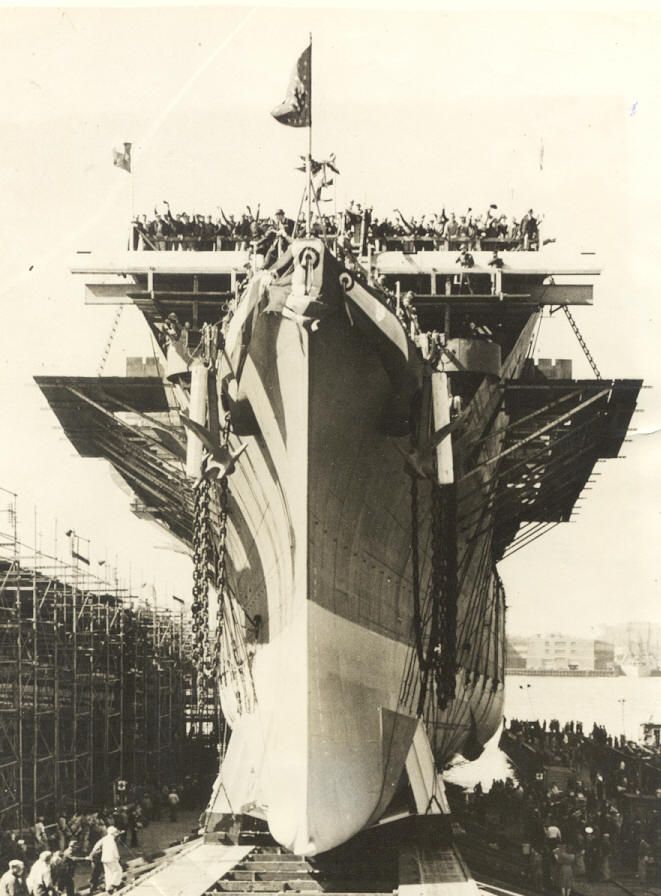

I don’t think the pilot survived. My uncle had a rubber inflatable raft in his parachute pack that was about the size of a sleeping bag, and no one knows how many days or weeks it was before he was picked up by another ship, but what I do remember was him telling me about the sharks, and I never forgot that. He was brought to Hawaii where he would recover in a hospital and where he was able to bring a grass skirt and leis home for my mother.

The type of raft the airmen who were shot down had: Lieutenant Junior Grade William R. Mooney, demonstrates how he paddled to shore after being shot down during raid on Guam, June 1944.

The U.S. Navy Cruise Book mentions the names of some of those planes and pilots shot down, but not my Uncle’s, and now I wished I’d asked him more about it, and about the typhoon. I find it hard to believe that no one seems to know the exact date he was shot down, something I will have to keep searching for. But by the time Air-Group Forty Five’s time on the San Jacinto was completed on May 1st, he was missing in action. He was missing for two months. My mother was 6 years old, and a telegram came to their house in Maspeth to let the family know. My uncle was awarded one of three Purple Hearts given to his air group, and he received 5 air medals, and according to my mother some other medals as well. He is eligible to be buried in Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia, which will be a story for another day. I found it comforting that my namesake was the group of islands the San Jacinto and my uncle would always go for rest and refuge during his whole time on that ship.

I suppose the best way to end this story is with an excerpt from the dedication at the back of the U.S. Navy Cruise Book: These boys gave up their youth to fight for this country. They carried the burdens of war in their mind until they died. What they experienced is unspeakable and showed tremendous bravery, honor and pride for the cause. They came home hardened and changed forever. They did the best they could to put the horrors or war behind them. They got married, created families and didn’t much think of themselves as heroes and seldom talked to anyone about their experiences. The price they paid brought freedom to the world, and generations could enjoy peace without fear of Tyranny.