This past spring and summer, our local cemeteries provided a tranquil refuge from the pandemic. But their primary purpose is to serve as final resting places for thousands of the deceased. There are two NYPD officers buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery who died in the line of duty, both about a century ago. One was the second black officer to join the force who became the first black officer to die in service. The other was a European immigrant, WWI vet and motorcycle cop. These are their tragic stories.

Robert Henry Holmes

Robert Henry Holmes was born in South Carolina in 1888. He moved to New York with his parents, Henry and Ella, at the dawn of the 20th century and they settled in Harlem. His mother worked as a laundress and housekeeper and his father was a porter. Robert attended a publicly financed co-ed boarding school for African-American children called Ironside in Bordentown, NJ. He then attended Howard University. Upon graduation, he joined the Black Elks Club, where he had become friendly with Samuel Battle, the trailblazing first – and up until that time, only – black officer on the NYPD. Robert decided to join the NYPD himself and Battle mentored him while he studied for the exam. Upon achieving active duty status in 1913, Robert was assigned to Harlem’s 28th Precinct, where Battle had previously been assigned. He made a big impact there, quickly becoming feared by the criminal element and beloved by the rest of Harlem. He later was transferred to the neighboring 30th Precinct where he and Battle were assigned to walk the same beat during different shifts.

Holmes worked his post located at West 139th Street and Lenox Avenue during the 4-12 shift on August 5, 1917. He was to be relieved by Sam Battle at midnight.

From the book One Righteous Man by Arthur Browne: “Just then the noise of a burglar opening a window awakened Garfield Rose in a first-floor apartment. Rose rushed to the window and struggled with the intruder. The burglar fired four shots and fled. Holmes ran toward the gunfire and gave chase on Lenox Avenue. The man darted into a building, snuffed a gaslight, and waited in the dark. Holmes dashed in and was felled by two shots to the head.”

The gunman fled but a suspect was later captured after an investigation. As word spread throughout Harlem that one of its favorite sons had been murdered, residents flooded the streets to mourn collectively. The devastating loss sparked a fundraising drive by multiple organizations to help support Holmes’ parents, who were both ill, and pay for a proper grave marker.

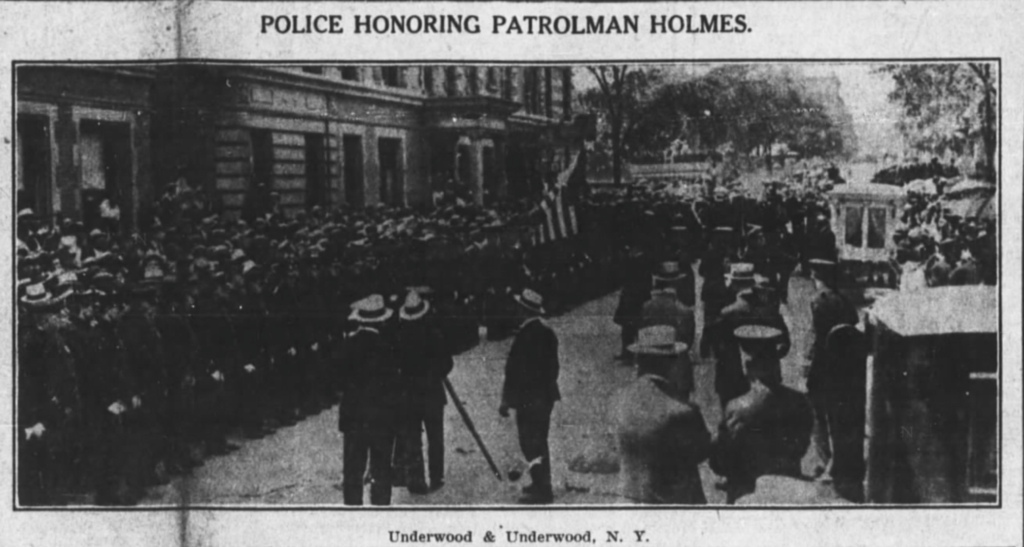

Holmes was awarded a full NYPD dress funeral. Twenty thousand mourners lined the streets of Harlem on August 15, 1917 to watch the procession to Bethel First AME Church on 132nd Street. A motorcade then escorted Holmes’ body to Mount Olivet Cemetery. The New York Age reported that so many had paid tribute to Holmes, “It required four carriages to carry the floral pieces to the grave.” Officer Battle accompanied Ella Holmes to the graveside service, her husband being too ill to attend. Ella watched in agony as her only child was lowered into the ground.

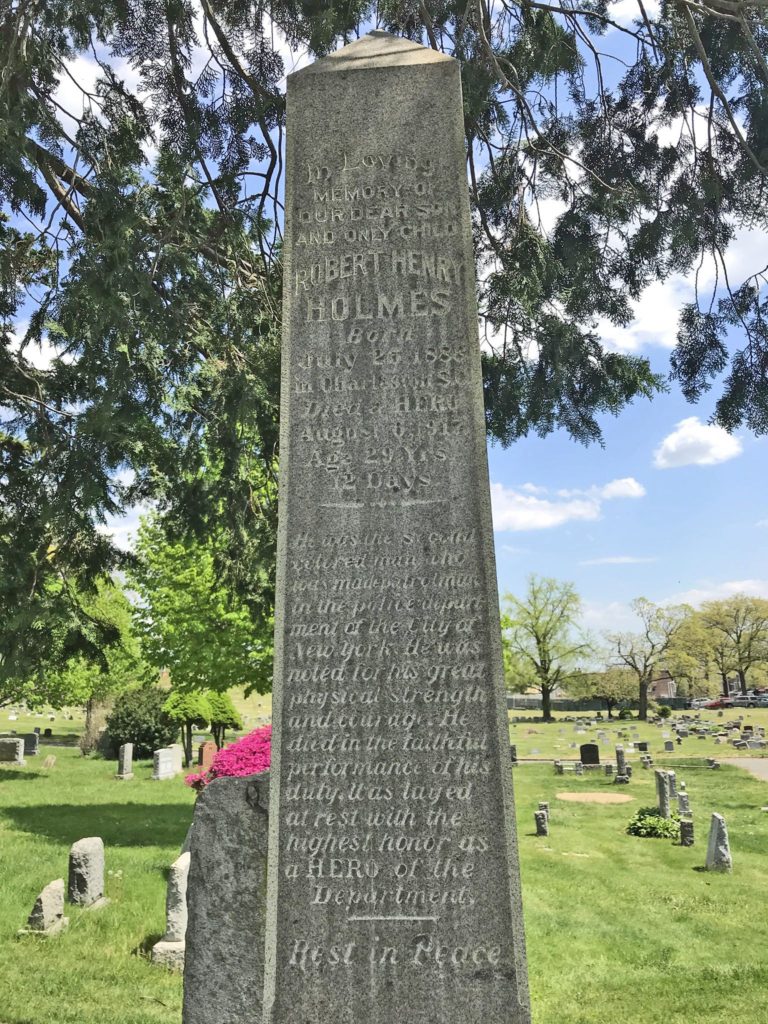

Henry Oliver Holmes died of pneumonia at the age of 50 on March 8, 1918, just 7 months after the loss of his son. Ella, in poor health herself, pressed on and unveiled the monument. The gravestone is in the shape of an obelisk. The inscription dedicated to Robert reads, “In loving memory of our dear son and only child, Robert Henry Holmes, born July 25, 1888 in Charleston, SC. Died a HERO, August 6, 1917, age 29 years and 12 days. He was the second colored man who was made patrolman in the police department of the City of New York. He was noted for his great strength and courage. He died in the faithful performance of his duty. Was layed at rest with the highest honor as a HERO of the Department. Rest in peace.”

Ella died at the age of 47 from postoperative shock after treatment for a uterine tumor on September 21, 1918. Her obituary in the New York Age stated, “She had just bought a plot and caused to be erected a monument and unveiled the same with fitting ceremonies to the memory of her brave son and said her life’s work was complete and she was ready to go. She planned and prepared her own funeral, leaving the same in charge of her loyal friend, Officer S.J. Battle.”

In just over the span of a year, all three members of the Holmes family had passed on and have rested in eternity together for more than a century. Holmes was posthumously awarded the NYPD Medal of Honor.

Mayor LaGuardia presided over the opening of the Police Athletic League located at 127th Street and 8th Avenue the evening of January 27, 1949, named the “Robert H. Holmes Youth Center” in honor of the fallen officer, 32 years after his death. Holmes’ story was recounted, and Taps was played on a trumpet. Scores of children subsequently benefitted from the programs held at and sponsored by the center. That building is now a church and today there exists no public monument to Holmes’ memory.

Ale Swider

Ale Swidersky was born in Antopal, Russia, which is now in Belarus, on November 25, 1900. At the age of 12, he immigrated to America with his family. They lived on the Lower East Side of Manhattan on Madison Street and were of the Russian Orthodox faith. At the age of 18, Ale was drafted into the US Army and sent to France during WWI under the name “Ale Swider” indicating that either Swidersky or the US Army shortened/further Americanized his surname (which accurately translated was actually “Sviderski”). Swider achieved the rank of sergeant in the infantry, served for just over a year, and was discharged in 1919.

Ale may have gained experience riding a motorcycle, still a relatively new technology, during the war. Motorcycles used in conflict were outfitted with sidecar mounted machine guns and placed together in motorized units called “Motor Mobile Infantry”. They could also be quickly converted into makeshift ambulances to transport the wounded.

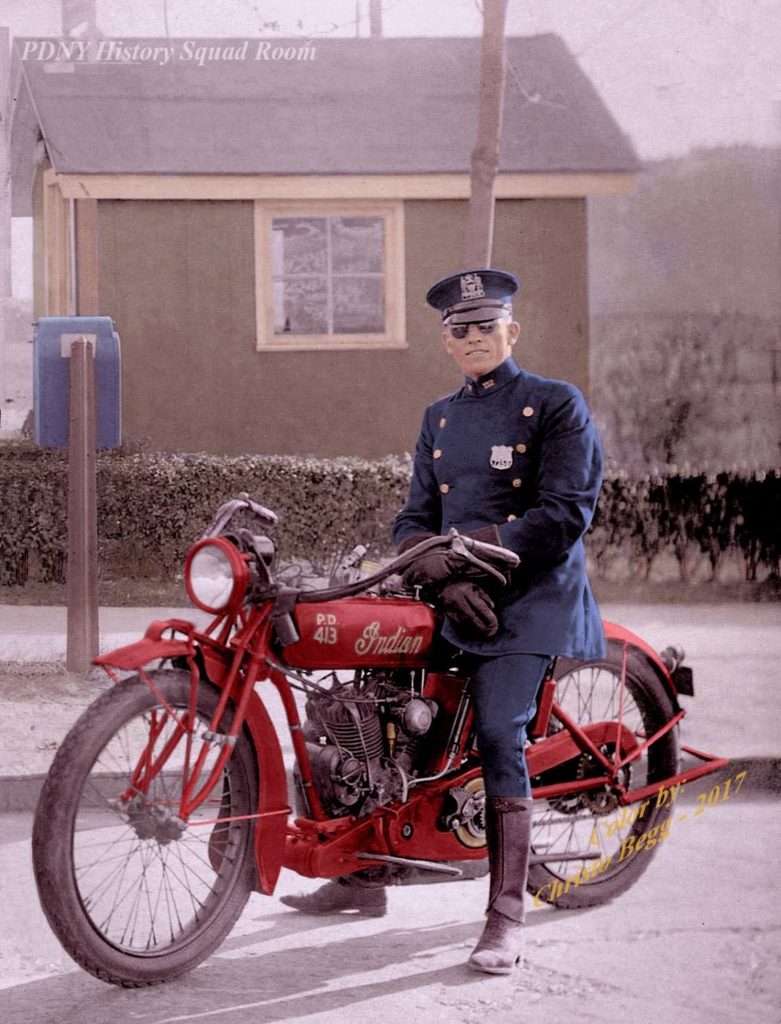

Patrolman Lloyd Curry of the 112th Precinct in Newtown shown riding one of

the department’s Indian Scout model motorcycles.

In 1921, Ale joined the NYPD which found him qualified to ride a motorcycle. The vehicles in service at the time were Indian Scout models, manufactured by the Indian Motocycle Manufacturing Company of Minnesota, a company that had manufactured motorcycles for the US Government during the war. They only manufactured them in the color of red, and the sight of a blue clad officer riding atop one provided a striking visual. Previous motorcycles were driven by belts or chains, but the Scout model had its gearbox bolted to a 610cc engine. It was considered to be the most reliable motorcycle out there, and police departments throughout the US and Canada purchased them for their fleets.

Swider was at first assigned to Manhattan’s 37th Precinct and later the 33rd Precinct where he was known as “Flash”. He regularly patrolled Central Park as its transverses were known speeding locations. An amusing anecdote was printed in the Daily News on August 23, 1923 about Swider’s interaction with a speedy motorist in the wee hours of the morning inside Central Park. When 30-year old Mrs. Madeline S. Korber went to Traffic Court to fight the ticket, the judge asked Swider to recall the encounter for the record. He stated, “I caught up with the machine driven by Mrs. Korber in Central Park near 106th Street at 2:15am in the morning of August 5. There were 2 men and another woman in the car which was going at 30mph. Mrs. Korber told me that she lived at 1287 West Nineteenth Street in Flatbush, Brooklyn and that she was searching the city for her dog.” Korber was found guilty and ordered to pay a $25 fine or spend 5 days in jail. She forked over the money.

Just about three months later, Swider was in pursuit of another motorist speeding through Central Park when he collided with a taxicab. Motorcycle cops of the era were not issued helmets, and although Swider survived the initial impact, his injuries were too severe, and the doctors at Reconstruction Hospital could not save him. He died November 2, 1923 at the age of 22 and was buried at Mount Olivet Cemetery on November 5. The Traffic Court on November 9 held a 5-minute silent tribute to Swider and Thomas Leonard, another motorcycle officer who had also recently died in Central Park in pursuit of a speeder. The cases that both had pending against 14 motorists were dismissed that day due to the late officers’ inability to testify.

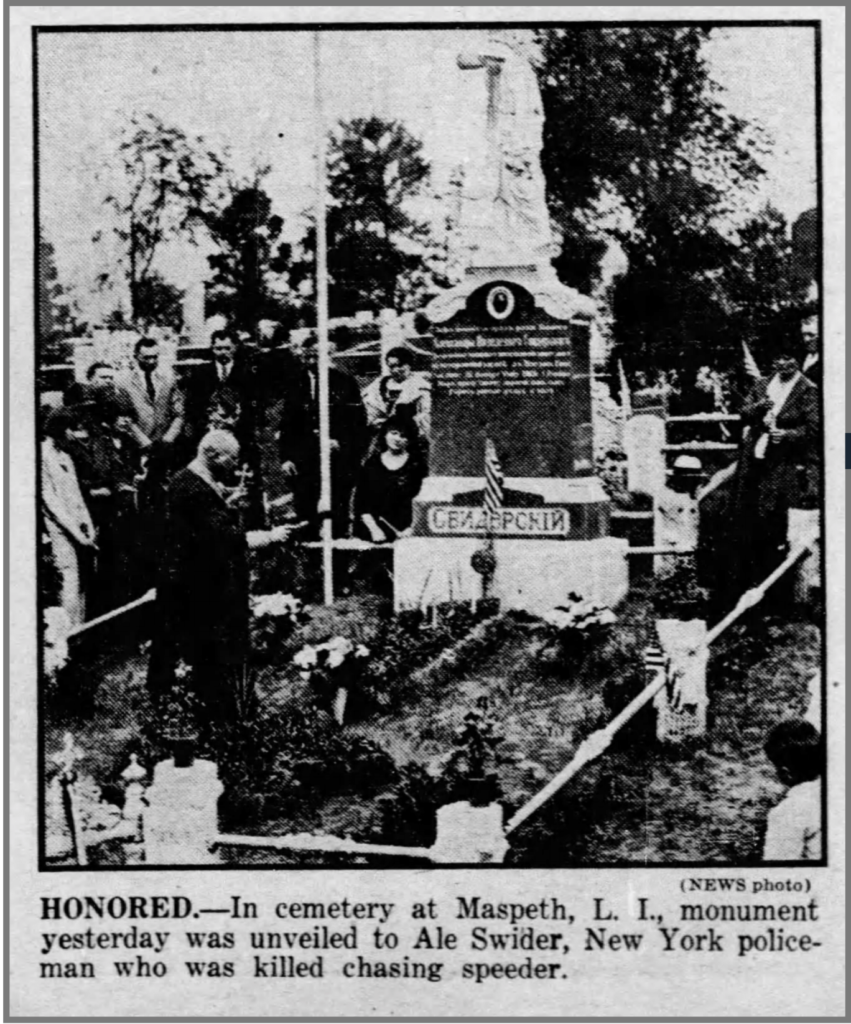

On June 15, 1924, the monument to Ale Swider was unveiled at his gravesite. Atop the monument is a bowed angel clutching at a cross with a Russian Orthodox cross beneath that. Further down a photo of Swider in uniform burned onto a porcelain oval ringed in gold paint. This “enameling” technique was brought to America in the early 20th century by Eastern European immigrants. The inscription, written entirely in Russian, translates, “Here lies the dust of God’s slave, Alexander Yakovlevich Sviderski, who perished before his time during his duties in government service in Central Park. Born on November 25, 1900, died on November 2, 1923. May your remains have peace, our dear son. In mourning, your father and mother.”

In the course of his short life, Ale Swider had grown up in Russia, immigrated to the United States, learned another language, helped win a world war and then served as a member of an elite NYPD unit. His is a very American story.

___________________________

Robert Henry Holmes and Ale Swider were two men who overcame different types of adversity to serve as police officers, both making the ultimate sacrifice in the performance of their shared duty to protect society. Both should be remembered and celebrated, and we plan to do just that.

JPCA and Newtown Historical Society will be honoring Robert Henry Holmes and Ale Swider on Saturday, September 19th at 10am with a procession and graveside memorial service at Mount Olivet Cemetery to commemorate “Thank a Police Officer Day 2020”. We invite the community to participate with us and our special guests. Please assemble at the main gate on Grand Ave by 9:30am.

___________________________

The following excerpt from an article in the New York Age dated August 16, 1917 explains how the suspected killer of Officer Holmes was identified and arrested:

Due to the efforts of Private Detective Shepard N. Edmonds, the police arrested Walter Hill, colored, of 121 West Spruce street, Stamford, Conn., who confesses to be the slayer of Police Officer Holmes. An old hat brought about Hill’s arrest.

Edward Fairchild, a shopkeeper of Stamford, has identified the hat found in the hallway where Holmes was murdered as the one he sold to Hill. Fairchild says that in April he sold a brown soft hat of Stetson make to Hill for fifty cents. It had been found on the street in front of his shop and purchased by Hill a short time later. Fairchild has positively identified Hill as the man to whom he sold the hat. It further has been established by the police that on the night of the murder Hill called on a girl residing at 14 West 138th street, where the crime was committed. Hill admitted to Assistant District Attorney Joyce Monday that he killed Policeman Holmes. At the conclusion of the confession, made after an all-night grilling in which detectives of the Fourth Branch took part, Hill was taken to Mount Vernon where he unearthed from beneath a hedge the revolver he had used.

Hill says he came from Stamford to New York to ”get even” with a certain girl with whom he had been friendly for two years, that he recently gave her $70 to have gold teeth put in and after she got the teeth, she deserted him. She was in the apartment he tried to enter and it was the man with her that he aimed at. The revolver was found on the estate of Norman M. Brown. Three shells had been discharged. Hill said he buried it after he had begged a ride to Mount Vernon on a delivery wagon. In the town, he was shot at by Policeman Schaeffer, but he escaped and begged another ride, this time to Stamford, where he was arrested Friday.

The hat which figured so prominently in bringing about Hill’s arrest was found by Detective Edmonds and turned over to the police. It was formerly owned by Harold F. Avery, 131 Riverside Drive. Detective Conkling went to Stamford and for several days tried to find out more concerning the hat and its ultimate owner. He finally learned that Edward Fairchild, who keeps a store at No. 48 West Main street, had sold such hat to a Negro. Fairchild said he knew Hill well, for at one time they had both worked for Robert M. Anthony at No. 248 Bradford street. He would be willing, he said, to swear the hat was the one Hill bought. Identifying Hill as the murderer mystified the police, as they were looking for a burglar and Hill was looked on as honest. But he was arrested. Then the police began to suspect that Hill was not after booty when he entered the West 138th street house.

On October 24, 1917, a jury convicted Walter Hill of the second-degree murder of Robert Henry Holmes, a fact which was reported in the press the following day. There are no published accounts of the trial or sentencing.