Things were done differently in Queens County in the early part of the 20th century. If one paid enough money to the right person, they could get away with just about anything. This may have been the case with Wayland Avenue (alternately called Way Avenue), a road that had reportedly been in use for more than 100 years when it was unceremoniously “bought” and closed by Lutheran Cemetery around 1904.

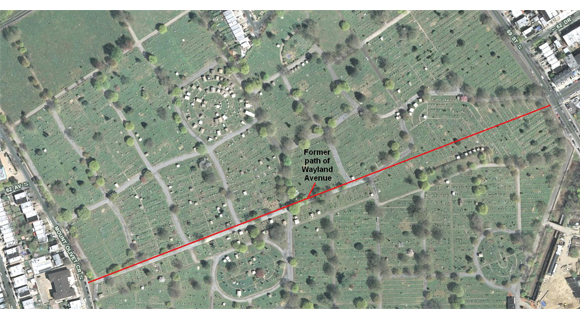

Today, this road would have been an extension of Juniper Boulevard South, but at the time it connected to Juniper Valley Road, which was back then the winding Juniper Swamp Road. Wayland Avenue ran between Mount Olivet Avenue (now Mount Olivet Crescent) and Juniper Avenue (now 69th Street).

The management of the cemetery at the time claimed that it had paid a fee to then Borough President Joseph Cassidy for rights to the road. Cassidy then arranged to have the road removed from official public maps published by the topographic bureau at borough hall. The cemetery subsequently erected a fence to keep travelers out and proceeded to bury bodies where the road had been. Under this deal, the graveyard gained more than 100,000 square feet of burial space. Cassidy administration officials claimed that Lutheran Cemetery promised to give up another slice of their land for the creation of Eliot Avenue, but the cemetery denied this.

The de-mapping of the street did not go unnoticed by neighboring townspeople. There were several homes near this stretch of road, and Wayland Avenue served as the only through street connecting western Maspeth (then known as Melvina) and Middle Village, unless a long detour was made to either Metropolitan Avenue or Grand Avenue.

Locals petitioned the Borough President for an investigation and the reopening of what was considered a “farmers’ highway.” By 1912, Cassidy and his successors – who were also his cronies – Joseph Bermel and Lawrence Gresser, were gone from office and the sitting borough president was Maurice Connolly, who joined residents in calling for the road to be reopened to the public. The Board of Estimate held hearings over the course of the next few years and ultimately ruled that the cemetery did not obtain the rights to the roadway via proper means, which included “consent of the cemetery authorities, 2/3 of the lot owners, and permission of the legislature.” The BoE demanded that the bodies be removed from the road and it be reopened to public passage. Connolly warned the cemetery that if they did not remove the fence by September 25th, 1916, he would have his workers from the Highway Bureau do it.

Connolly was set to take action on the deadline day when he was notified that the cemetery had obtained a temporary injunction from the Queens County Supreme Court. Not wanting to be found in contempt of court, Connolly told his men to stand down. Cemetery officials told the judge that Wayland Avenue was actually a small private lane at the time it was purchased, along with the rest of the land around it, in 1891. It did not have a name at that time, but was called “the old road leading to the Methodist meeting house.” Travelers along the road were rare, and the cemetery used the fact that the city had never improved the street as evidence that the road was never public.

The treasurer of the cemetery declared that “there are now 1,400 bodies buried in the tract, that there are 690 owners of plots in the former street and that the mausoleums, tombs, headstones and vaults erected in the tract have a value of over $500,000.” The Rev. David Peterson was the pastor of Trinity Lutheran Church, which at the time was located inside Lutheran Cemetery. He testified that he lived for many years at the corner of Mt. Olivet Avenue and the lane leading to the old Methodist meeting house and that the road was hardly ever used by the public.

Connolly admitted that the road was never officially opened, but that it became a legal street by default. His argument was that its continual use by the public made it city property. The judge directed that the Borough President show cause why the injunction should not be made permanent. As evidenced by the lack of a public path through Lutheran Cemetery today, Connolly failed to do so.

After years of wrangling in courts and the legislature, Eliot Avenue, which had been planned as far back as the 1890s, was finally cut between Lutheran and Mount Olivet Cemeteries in 1938. The amount of land given up by Lutheran Cemetery for this project was about ¼ of the land they had gained by closing Wayland Avenue.

If you look at an aerial view of All Faiths Cemetery today, you can easily spot the road that once was part of Wayland Avenue.