In the aftermath of the August 4th tropical storm Isaias that hit the City of New York with its gale force winds and powerful gusts, news reports focused on the usual outcome of storms – personal injury and death, property damage, the disruption of transportation and services by blocked roads, power outages, and of course the high financial cost of it all. Our experience of dealing with storms is not new for residents in this “Boro of Trees”. We recall the EF-1 Tornado (2010), Hurricane Irene (2011), Hurricane Sandy (2012), and now Tropical Storm Isaias. Whereas cleanup is in progress, there is one thing most certain about this storm event. The underlying thread that connects the storm related damage, disruptions and disturbance are from the wind-induced catastrophic failures of large street trees and tree limbs.

There is no doubt that many readers have a great appreciation and fondness for tree-lined streets with its verdant canopies contributing to important neighborhood greening. Homeowners are rightly concerned about the delivery by the City of New York and NYC Parks Forestry Division of reasonable and effective arboricultural tree care by vetted tree care professionals, and with long-term urban forestry management methods that includes assessing the risk condition that trees pose to the public. With that, many are willing to accept and live with a certain level of tree risk under normal conditions (certainly a low level of risk is desirable), because it is offset by a myriad of tree amenities. Those amenities exist in the form of well-known benefits and services that large street trees deliver to people and the environment. Whether it is for shade and cooling, storm water run-off absorption, feelings of well-being among trees, air quality amelioration and carbon absorption, lower crime incidences, neighborhood attractiveness, increases in property value and even oxygen production.

By casual observation, one easily recognizes two distinct characteristics about street trees; that large trees are more likely to fail than small trees (in gale force winds) and, that the disruptions in services and damage to property are not because of storms but rather the existing structural condition of trees when the storms hit. The tree science tells us one needs to separate the physiological health of a tree with that of its structural wood strength, also referred to as tree biomechanics. A tree could appear absolutely healthy with a full crown, have robust incremental growth and with normal performance. Yet the tree can also be structurally inferior and loaded with unacceptable defects within tree wood- to the level that it poses a risk to the public. For this complex woody organism it is the latter, tree structure that for the most part determines whether a tree remains upright or whether it fails. Tree failure can occur on its own by gravity (a seldom occurrence) or, induced to failure by high force winds acting upon the tree crown. But it is winds of the storm that will push tree structure to its limits. Absent timely inspections for condition and risk assessment by a trained arborist or municipal forester, it is unlikely then that any mitigation “specific for the reduction or elimination of that tree risk” would ever take place.

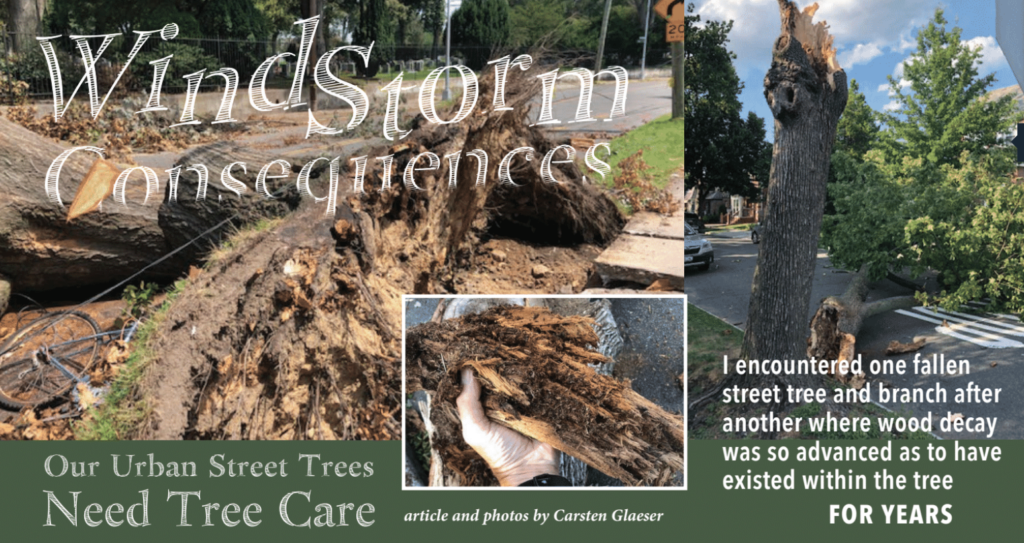

Isn’t that precisely what is observed? There are thousands of trees with defects that lead to root, trunk and branch failures. Some of those trees occurred as “wind throws”, a forestry term that describes the uprooting of entire tree, unable to remain upright due to a combination of a improper installation, root defect, restricted rooting area and inferior soils. But most street trees experienced significantly diminished tree wood strength from years of fungal wood decay activity within the tree trunk and branches. I encountered one fallen street tree and branch after another where wood decay was so advanced as to have existed within the tree for years. How did that decay get there? Fungal spores exist in the air and are introduced to the tree cambium by any number of wounding episodes throughout the life of the tree such as; by tree un-friendly mechanical excavations by contractors and builders, wounding from moving trucks, weed wackers and mowers, and even by egregious tree branch pruning practices by approved NYC contracted tree trimming firms, and others.

Wood decay within the tree can be detected and evaluated with frequent inspections, an essential element of a sound urban tree management program. Who is it that is managing our important street trees to ensure a reasonable duty of care, and for tree risk? In the tree care profession it is the Certified Arborist with the skillset to diagnose, evaluate and assess a defect for risk, with readily available arboricultural tools and with reasonable inspection frequency.

Yet by this storm and with thousands of tree and tree limb failures, it is revealed that the nature and accuracy of street tree inspections by its municipal Foresters (as Certified Arborists) – for tree structural condition and for tree risk – is duly lacking in its effectiveness to minimize catastrophic tree and branch failures. This suggests that those within the agency who should have the professional wherewithal to manage rather than mismanage this important living resource, need to critically revamp and scale up the agency’s tree inspection methods and frequency.

It is the only way to place greater public confidence back into the term, Tree Care.

Carsten W. Glaeser, Ph.D. Is an ISA Certified Arborist & ISA Qualified Tree Risk Assessor and works as an independent consulting arborist for Glaeser Horticultural Consulting, Inc.