It was cold, windy, and rainy in Washington, and the President was ill. A week earlier, Abraham Lincoln had delivered the Gettysburg Address after sitting outside for two hours listening to Edward Everett orate. Now, in the last week of November 1863, Lincoln was “quite unwell,” suffering from a mild form of smallpox called varioloid. Despite his poor health, his humor remained intact; he remarked that “since he had been President, he had always had a crowd of people asking him to give them something, but that now he has something to give them all.” The timing of the President’s illness was unfortunate. That Thursday, the fourth Thursday in the month of November, marked the day that Lincoln had set aside for the first official national Thanksgiving Day.

Nearly two months earlier, while living at the Soldiers’ Home, Lincoln had issued a proclamation on October 3, announcing that “I do therefore invite my fellow citizens in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and those who are sojourning in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise.” Though this was not the first Thanksgiving Day proclamation that a President had issued – in fact Lincoln himself had issued several before this one – the 1863 declaration is credited with officially establishing a national holiday observed on a late Thursday in November.

“To the service of that great and glorious Being”

Though Thanksgiving traces its roots to the original pilgrim thanksgiving in the Plymouth colony, the practice —specifically around late November — was not firmly established in American society at-large through the colonial era and early decades of the republic. Individual colonies celebrated several thanksgivings during the calendar year, though as per Puritan customs these usually were days full of fasting and prayer, not bountiful feasts and social gatherings.

During the Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress often prescribed various days of thanksgiving through- out the year, yet these were considered “recommendations” to the state executive and legislative bodies. These often followed major victories in battle, such as the Battle of Saratoga in the fall of 1777, and were framed in terms of the prevailing Christian beliefs. For example, the November 1, 1777 Thanksgiving Day proclamation issued by the Continental Congress explicitly recommended Americans to express their gratitude in order to receive Jesus Christ’s forgiveness for their sins.

As President, George Washington continued the tradition of issuing proclamations marking single days as days of “thanksgiving.” Exactly 74 years before Lincoln issued the proclamation that would establish the annual National Day of Thanksgiving in November, Washington issued a Thanksgiving Day Proclamation. The October 3, 1789 announcement read in part “Now therefore I do recommend and assign Thursday the 26th day of November next to be devoted by the People of these States to the service of that great and glorious Being, who is the beneficent Author of all the good that was, that is, or that will be.” Though less overt than some earlier proclamations, religion was still the underlying reason for this proclamation. In the end, however, this order from Washington did not permanently establish an annual tradition (Washington did not announce another thanksgiving day until 1795).

For the next 65 years thanksgivings were established by governors of individual states, mostly in New England and other parts of the North. Presidential announcements were occasionally issued. Adams declared Thanksgivings in 1798 and 1799 and Madison renewed the tradition in 1814 after the War of 1812 ended, and also declared two days of thanksgiving in 1815. Though some states refused to create Thanksgivings, claiming they were remnants of Puritan religious zeal, 25 out of 32 states issued some kind of thanksgiving proclamation in 1858 on the eve of the Civil War.

“Acknowledge and render thanks to our Heavenly Father”

As the Civil War wreaked havoc on the nation, Lincoln issued several thanksgiving proclamations to help the nation cope with the tragedy while remaining grateful that things were not worse. The first was a fairly unremarkable issuance on November 27, 1861 announcing that “the municipal authorities of Washington and Georgetown in this District, have appointed tomorrow, the 28th instant, as a day of thanksgiving, the several Departments will on that occasion be closed, in order that the officers of the government may partake in the ceremonies.” This order was something of an anomaly for Lincoln’s thanksgiving proclamations. First, it was specific to the District of Columbia, whereas sub- sequent ones would be more national in focus. Second, due to the localized nature of the celebration, Lincoln ordered the day of thanksgiving less than 24 hours in advance. Third, and most importantly, the order was devoid of the religious and spiritual language that dominated his other Proclamations of Thanksgiving. This statement reads more like a routine memo than the appeal for national unity and gratitude that his later statements would inspire. (In fact, it was titled “Order for Day of Thanksgiving” as if it were coming from the Commander-in-Chief.)

The second officially released proclamation was more important. It came just three days after the Union’s victory at the Battle of Shiloh on April 7, 1862. In it, Lincoln recommended the “People of the United States… at their next weekly assemblages in their accustomed places of public worship which shall occur after notice of this proclamation shall be received” to “acknowledge and render thanks to our Heavenly Father for these inestimable blessings” of victory in battle. In addition to this religious gratitude, Lincoln implored the nation to remember and honor “those who have been brought into affliction by the causalities and calamities of sedition and civil war.”

It was cold, windy, and rainy in Washington, and the President was ill. A week earlier, Abraham Lincoln had delivered the Gettysburg Address after sitting

outside for two hours listening to Edward Everett orate. Now, in the last week of November 1863, Lincoln was “quite unwell,” suffering from a mild form of smallpox called varioloid. Despite his poor health, his humor remained intact; he remarked that “since he had been President, he had always had a crowd of people asking him to give them something, but that now he has something to give them all.” The timing of the President’s illness was unfortunate. That Thursday, the fourth Thursday in the month of November, marked the day that Lincoln had set aside for the first official national Thanksgiving Day.

Nearly two months earlier, while living at the Soldiers’ Home, Lincoln had issued a proclamation on October 3, announcing that “I do therefore invite my fellow citizens in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and those who are sojourning in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise.” Though this was not the first Thanksgiving Day proclamation that a President had issued – in fact Lincoln himself had issued several before this one – the 1863 declaration is credited with officially establishing a national holiday observed on a late Thursday in November.

“To the service of that great and glorious Being”

Though Thanksgiving traces its roots to the original pilgrim thanksgiving in the Plymouth colony, the practice —specifically around late November — was not firmly established in American society at-large through the colonial era and early decades of the republic. Individual colonies celebrated several thanksgivings during the calendar year, though as per Puritan customs these usually were days full of fasting and prayer, not bountiful feasts and social gatherings.

During the Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress often prescribed various days of thanksgiving through- out the year, yet these were considered “recommendations” to the state executive and legislative bodies. These often followed major victories in battle, such as the Battle of Saratoga in the fall of 1777, and were framed in terms of the prevailing Christian beliefs. For example, the November 1, 1777 Thanksgiving Day proclamation issued by the Continental Congress explicitly recommended Americans to express their gratitude in order to receive Jesus Christ’s forgiveness for their sins.

As President, George Washington continued the tradition of issuing proclamations marking single days as days of “thanksgiving.” Exactly 74 years before Lincoln issued the proclamation that would establish the annual National Day of Thanksgiving in November, Washington issued a Thanksgiving Day Proclamation. The October 3, 1789 announcement read in part “Now therefore I do recommend and assign Thursday the 26th day of November next to be devoted by the People of these States to the service of that great and glorious Being, who is the beneficent Author of all the good that was, that is, or that will be.” Though less overt than some earlier proclamations, religion was still the underlying reason for this proclamation. In the end, however, this order from Washington did not permanently establish an annual tradition (Washington did not announce another thanksgiving day until 1795).

For the next 65 years thanksgivings were established by governors of individual states, mostly in New England and other parts of the North. Presidential announcements were occasionally issued. Adams declared Thanksgivings in 1798 and 1799 and Madison renewed the tradition in 1814 after the War of 1812 ended, and also declared two days of thanksgiving in 1815. Though some states refused to create Thanksgivings, claiming they were remnants of Puritan religious zeal, 25 out of 32 states issued some kind of thanksgiving proclamation in 1858 on the eve of the Civil War.

“Acknowledge and render thanks to our Heavenly Father”

As the Civil War wreaked havoc on the nation, Lincoln issued several thanksgiving proclamations to help the nation cope with the tragedy while remaining grateful that things were not worse. The first was a fairly unremarkable issuance on November 27, 1861 announcing that “the municipal authorities of Washington and Georgetown in this District, have appointed tomorrow, the 28th instant, as a day of thanksgiving, the several Departments will on that occasion be closed, in order that the officers of the government may partake in the ceremonies.” This order was something of an anomaly for Lincoln’s thanks- giving proclamations. First, it was specific to the District of Columbia, whereas subsequent ones would be more national in focus. Second, due to the localized nature of the celebration, Lincoln ordered the day of thanksgiving less than 24 hours in advance. Third, and most importantly, the order was devoid of the religious and spiritual language that dominated his other Proclamations of Thanksgiving. This statement reads more like a routine memo than the appeal for national unity and gratitude that his later statements would inspire. (In fact, it was titled “Order for Day of Thanksgiving” as if it were coming from the Commander-in-Chief.)

The second officially released proclamation was more important. It came just three days after the Union’s victory at the Battle of Shiloh on April 7, 1862. In it, Lincoln recommended the “People of the United States… at their next weekly assemblages in their accustomed places of public worship which shall occur after notice of this proclamation shall be received” to “acknowledge and render thanks to our Heavenly Father for these inestimable blessings” of victory in battle. In addition to this religious gratitude, Lincoln implored the nation to remember and honor “those who have been brought into affliction by the causalities and calamities of sedition and civil war.”

This proclamation was a critical step towards the national holiday we celebrate today, although it did not go so far as to establish modern Thanksgiving. Besides being issued in April and not November, the proclamation did not specify a date on which the entire nation would unify and give its thanks. Furthermore, just like the earlier proclamations from the Continental Congress, Lincoln connected the day to religion — recommending the day be celebrated in the American people’s places of public worship — whereas people today associate Thanksgiving with home and family, not church and god. Lastly, due to the specific military situation of the nation, Lincoln requested that Americans pray for “those who have been brought into affliction by the causalities and calamities of sedition and civil war.” Thus, not only was this a step toward what we now know as Thanksgiving, but Lincoln’s proclamation perhaps foreshadowed national days of honoring soldiers like Memorial Day and Veterans Day as well.

“Acknowledged as with one heart and one voice by the whole American People”

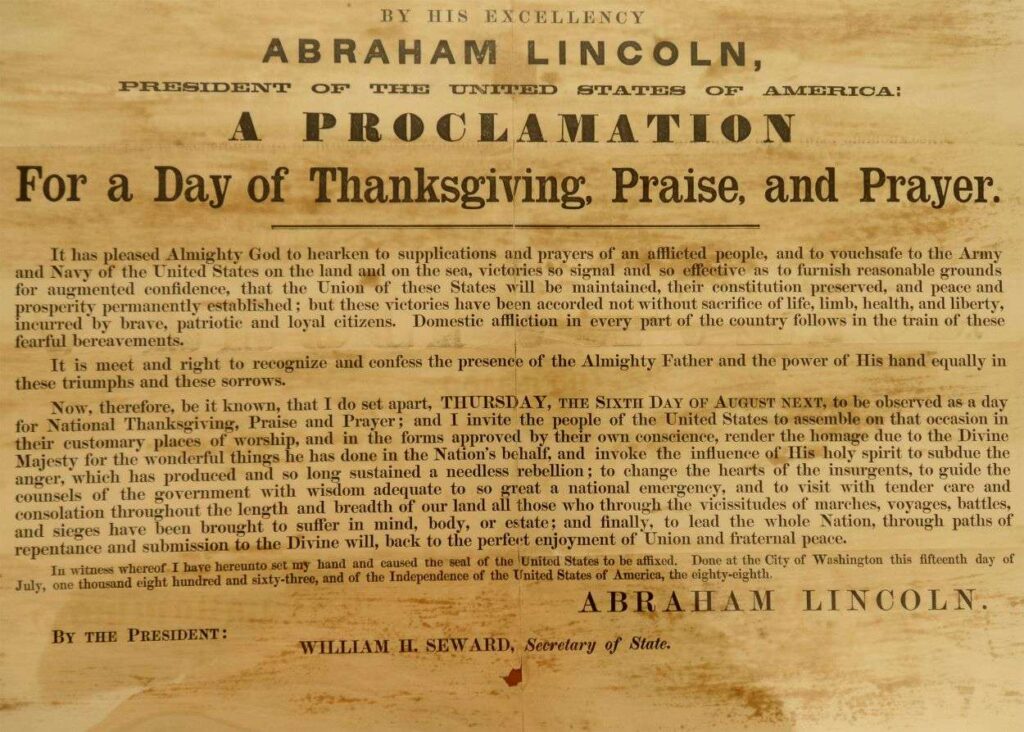

Lincoln issued another Proclamation of Thanksgiving in mid-July 1863 in gratitude of the Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg two weeks prior. Unlike the November 27, 1861 proclamation which only applied to DC, or the April 10, 1862 declaration which did not specify a single day, this proclamation established August 6 as a national day set aside for prayer. However, this one-time observance was not enough for 74-year-old magazine editor Sarah Josepha Hale. Originally from New England, Hale, the editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book, had been pushing for a national Thanksgiving Day since 1846. She had sent letters to Lincoln’s predecessors Zachary Taylor, Millard Fillmore, Franklin Pierce, and James Buchanan asking them to officially fix Thanksgiving to a specific date. None of them responded. Finally, she wrote President Lincoln a letter dated September 28, 1863, saying “You may have observed that, for some years past, there has been an increasing interest felt in our land to have the Thanksgiving held on the same day, in all the States; it now needs National recognition and authoritive [sic] fixation, only, to become permanently, an American custom.” Lincoln responded by issuing the proclamation of October 3 that firmly established Thanksgiving as a national holiday on the last Thursday of November. In the Proclamation, which was hand-written by Secretary of State William Seward, though signed off and approved by Lincoln, the nation was reminded that “The year that is drawing towards its close, has been filled with the blessings of fruitful fields and healthful skies” despite the bloody conflict. “In the midst of a civil war of unequaled magnitude and severity … peace has been preserved with all nations, order has been maintained, the laws have been respected and obeyed, and harmony has pre-

vailed everywhere except in the theatre of military conflict; while that theatre has been greatly contracted by the advancing armies and navies of the Union.” Thus, “it has seemed to me [i.e. Lincoln] fit and proper that [these blessings] should be solemnly, reverently and gratefully, acknowledged as with one heart and one voice by the whole American People.”

Lincoln, via Seward’s writing, wanted Americans to come together as a nation and show their thanks for national progress, despite the ongoing conflict. This became the first annual National Day of Thanksgiving in late November. (From 1863 until 1938, Thanksgiving was celebrated on the last Thursday of November. In 1939, when Thanksgiving fell on the fifth Thursday of the month, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt changed the day to the fourth Thursday in order to stimulate post-Thanksgiving Christmas sales during the Great Depression.)

In addition to the national day established in 1863, Lincoln still issued “special occasion” measures of thanksgiving, including one on September 3, 1864, just days after Atlanta fell to Union forces. The next month, Hale sent Seward a letter dated October 9 reminding him of the upcoming holiday and hoping that “President Lincoln will [issue] his proc- lamation appointing the last Thursday in November as the Day.” By issuing the proclamation sooner rather than later, “the important paper would have time to reach the knowledge of American citizens in Europe and Asia, as well as throughout our wide land… [If], on land and sea, wherever the American Flag floats over an American citizen, all should be invited and unite in this National Thanksgiving, would it not be a Thursday in November next as a day, which I desire to be observed by all my fellow-citizens wherever they may then be as a day of Thanksgiving.” When Americans observed the holiday the fol- lowing November it marked two straight years of celebrating Thanksgiving on a late Thursday in November. The modern tradition was established.

Article originally published by President Lincoln’s Cottage, a historic site and museum in Washington, DC. Learn more at www.lincolncottage.org.