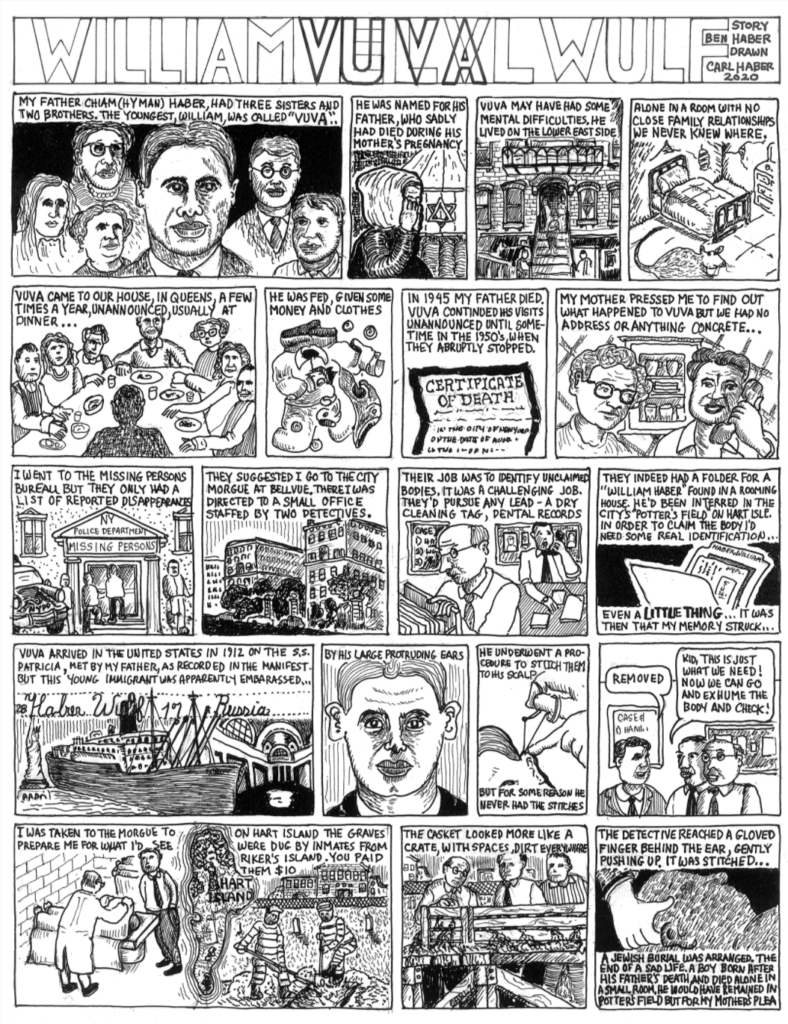

My father had three sisters and two brothers. The youngest was named William but was called Vuva. Why not Velvel, Yiddish for William? I do not know. Vuva it was. He was named after his father, and one may ask how could he be named after his father, since in some elements of the Jewish faith, it is prohibited to name someone after a living person? The answer is, his father died while his mother was still pregnant with him.

Vuva never married. He was semiliterate and may have had some mental difficulties. He lived in a room somewhere on the lower East Side in Manhattan and I think he earned some money working in a shop that repaired luggage. He had nothing except the clothes on his back and the paltry dollars he earned. He did not have a close relationship with most family members except for my father and mother. He came to our home several times a year, always unannounced, usually at dinner time. He was given dinner, a few dollars and any clothing my parents could spare.

When Vuva was told my fifty-two-year old father died, it did upset him. He continued to make his unannounced visits until sometime in the early 1950s, then he stopped coming. My mother, while only a sister-in-law, and a kind, caring, decent person, was disturbed that something may have happened to him and she pressed me to find out. This was not easy since we had no specific address, or anything concrete to pursue.

I went to the Missing Persons Bureau of the New York City Police Department, but it only had a list of persons reported missing with concrete information about the person. While that was of no help, I was told to check with the New York City morgue located in the Bellevue complex on First Avenue in Manhattan. I went there and was directed to a small office that was staffed by two or three New York City detectives whose job it was to identify unclaimed dead bodies. They were a very dedicated group. It was a challenge for them to identify every corpse and connect it with family. They had a chart on the wall that listed their progress and how many bodies remained unidentified by the end of the year, and it was never more than a few. They explained they would pursue whatever leads they had such as dental records, dry cleaning tags and anything else at their disposal. They explained that I would be surprised how often even “little things” led to identifications.

When I explained why I was there, they checked their records and retrieved a folder marked “William Haber”. A body was found in a rooming house in the lower East Side and they were told by the landlord, it was a William Haber. There were no papers indicating the names or addresses of relatives. An autopsy had been performed and the file indicated a male Caucasian in his late forties. He had an abdominal scar suggesting at an earlier date surgery in that area of his body. The body, while subject to some rat bites probably occurring after death, suggested the death had occurred a short period of time before it had been found. Since there was no way to make a connection to family, the body had been interred about six months prior to my visit in Potter’s Field, the city burial place for unclaimed bodies.

I had difficulty understanding why since they had a name it wasn’t enough evidence, but they had the last word. As I was about to leave, I suddenly stopped with what may have been a lightning bolt in the form of a “little thing but infinitely most important”. It caused me to remember something else about Vuva. I told the detectives I suddenly recalled being told at some point, that when Vuva came to the United States, he felt embarrassed his ears appeared to be very large and protruded a great deal from the side of his head. He was told if he had his ears stitched to the side of his head, left it in place for a few months and the stitches then removed, the ears would stay back. He underwent the procedure, but never had the stitches removed.

I figured since the body had been buried with no way to examine it, what good was what I now remembered? Well, I was wrong. The detectives became excited and said they could arrange for two inmates from Rikers Island to come to Potter’s Field and dig up the grave. I would have to give each of those men $10.00. There was of course no way to determine the condition of the body at this time, but they believed it was worth the effort. I told the detectives I would think about it. There was no way I would have my mother at Potter’s Field to witness the excavation. I spoke to family members to find someone who would accompany me but no one agreed to go, and if it was going to happen, it was clear, it had to be me.

I returned and told the detectives I would go ahead with the excavation, but at my young age of 20 I was unsure I had the stomach to look at a deteriorated body. They took me into the morgue section and pulled open about six sliding draws that contained dead bodies in various deteriorated conditions. It did not upset me, and I gave the detectives the go ahead. A month later when I came to Potter’s Field, the grave was dug up and the body removed. It had been buried in a small loose wooden box with much dirt on the body. While the body still had some skin on it, the face was not recognizable, but the ears were intact. One of the detectives, with rubber gives on his hands, moved the dirt away, leaned over and with one finger slipped under an ear, and moved it gently upwards. Halfway up the finger could not move any further. It was clear the ear was stitched to the side of the head, the identification complete, and without question it was Vuva.

Arrangements were made to have the body removed, prepared and placed in a proper coffin for a burial in a Jewish cemetery. It was the end of a sad life in which a baby had been born after his father died, possessed nothing of any material value and died alone in a rat-infested room. Were it not for my mother, his sister-in-law, he would have spent eternity in Potter’s Field. Only the sudden recall of a long forgotten “little most important thing” – stitched ears – made possible a clear identification.