To labor to survive, find work, start a business, sacrifice, fight, make a better life for yourself and pass it on to your family – many an immigrant’s heart beat to this progression of the American dream.

“What happened to the bread?” puzzled my mother, feeling the peach fuzz of my crew cut.

P&M Italian-American Grocery stood off Stanhope Street, between Charlie’s Candies and the corner funeral parlor. On my way up the winding stairs three flights above my father’s store, I could not help but gnaw the end off the large sesame seed bread that I can still smell and taste forty years later. Fresh, crisp, soft to the bite. Sometimes, I still find such Brooklyn bread.

The world first came through story book images, “The Little Red Caboose,” then kindergarten, those milk containers and mini-Hostess snowball cookies, then the neighborhood, like the time a drunk climbed a street lamp two stories high. Stranded, he teetered on his belly over the street with fire trucks flashing all about, firemen figuring how to get him down safely.

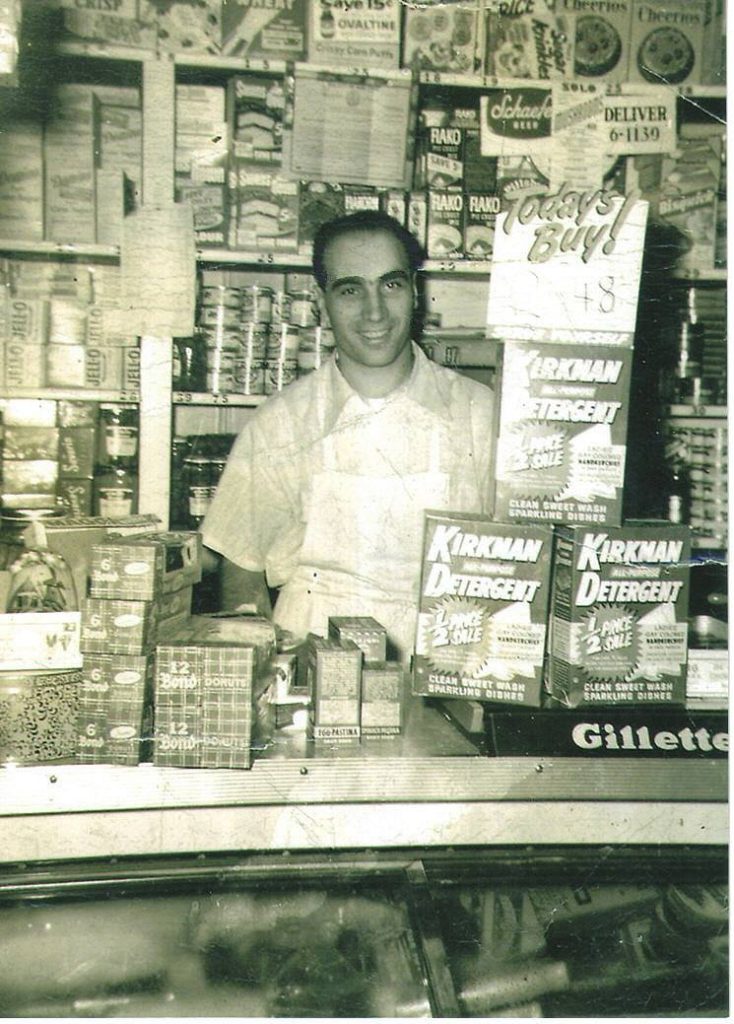

While grandma and grandpa watched the children, my parents split day shifts along with my aunt and uncle, giving each family every other Sunday off, opening each day before the 6am milk delivery. A black Chevrolet Nomad station wagon served as a delivery pick-up for extra quarts and loaves and posed as a two-family car. Across the store windows, hung with various sausages and cheeses imported from Italy, the steel gate rattled shut on each side of the door at 11pm. Once my favorites, Oldani salami, sliced thin, piled thick and Fondutto cheese with a mild taste fit for the gods; now, deli owners answer with a shrug, “Never heard of it.”

My older brother, brain damaged by forceps at birth, needed to be fed and carried to his wheelchair donated by the March of Dimes. Lena, my mother, proclaimed it the only organization that ever gave her anything for free, and placed a dime in their donation stand-ups whenever she saw one. Malpractice was not what it is today. I was a cesarean. My younger brother John came when I turned seven as my older brother Robert passed away at twelve.

Out front and around the block, the sidewalks and streets served as playgrounds and ball fields, nearer to home and less dangerous than the real thing. You could master the chalk board created for Skelzies, tough on fingers (a game played by flicking bottle caps across the pavement, something for which a grocer’s son had the finest supply), or with a coat hanger improve your fine-motor skills by fishing Spalding or Pennsy Pinky rubber balls up from the sewers. As you got older, you graduated from stoop ball (bouncing a ball off concrete steps), or box ball (played between sidewalk squares of cement), to stick ball in the street with manhole covers and car tires for bases. Hit the ball onto the roof and you are out. As it was hard to find a decent schoolyard wall to play handball, dad on occasion made time to drive us to Highland Park for picnics (the forest was a reservoir then), play catch and mushroom-pick, while minding the poison ivy.

The candy store was king. Seventy-five cents bought an official stickball bat replacing an assortment of broom and mop handles. Nothing compared to egg creams, hot dogs, comics and baseball cards, except maybe a trip to a real ballgame.

Of course, there lurked the bully and had-to-play-to-fit-in idiocy games like knuckles and manhunt. But whether my knuckles glowed red (beaten raw with the deck after losing this card game), or my arms were punched-up from the manhunt version of hide-and-seek, I could always make my way back to the safety of my dad’s store.

Every inch was filled with something. The grocery made its profits in pennies – a few pennies on a can of tuna or tomato sauce, a few cents on corn flakes, vanilla cream soda, ice cream, peaches, detergent, cherries in brandy and anything that could be stuffed on the shelves. It added up until ends were met. Bills, inventory, stock, orders, rent, food and the rest of life demanded a tremendous amount of work. Ignorant of ethics, unconcerned with the labors of others, the occasional shoplifter put a drain on your efforts.

A young man tried, but was unsuccessful at, sneaking a package of Twinkies into his jacket pocket.

“I’ll pay for it!”

“I don’t want you to pay for it.” Refusing to use foul language, my father put a curse on thieves in Italian. So after a pause, building steam, “Stramaledissa!” fired my father. This signal sent my uncle Louie hurdling over the bananas and onions toward the entrance as customers cleared the main aisle.

“Angelo, don’t kill him!” my mother or Aunt Jean called. The usual routine: my uncle would swing open the door as my dad rounded the counter, and the astounded culprit (collared by the jacket and pants), flew out like a bird, but landed like a heavy sack of potatoes onto the sidewalk. My uncle closed the door. My dad returned the Twinkies to the shelf and went back to work behind the register.

It was a minor delay, as sanitation, police, firemen, construction workers from every source awaited lunch heroes piled high with cold cuts such as roast beef, turkey, mortadella, and cheeses like Swiss, Muenster, Provolone – dozens of choices – mustard or mayonnaise on Italian or French bread with a pickle, lettuce and ripe beefy tomatoes from the yard (not legal, but so delicious you could eat them like apples). And at day’s end, the scraps of leftover meats went to the cats out back and the supply room’s very own feline. A good mouser is a store’s best friend.

I never liked breakfast. I knew my mom would sneak an egg into my chocolate milk to compensate, but I could not taste it so I did not mind. Grandma even tried serving hotdogs, which worked for a few days until she swept and discovered that I would eat the middle and drop the buns behind the couch. One morning, a new commotion took place downstairs. A gang leader drove up with his followers after he received the usual “special exit” for stealing a six pack of Ballentine beer. “I’m going to break up the block,” quote he. The law functioned different in those days. My dad grabbed him and dented a car fender with the gang leader’s head then twisted the antenna around his neck. Charlie rushed from the candy store with a bat and the funeral parlor emptied out. By the time the police arrived, the parlor’s immaculate white walls sparkled with spattered crimson and lined up gang members, making it easy for the police to clean up, so to speak.

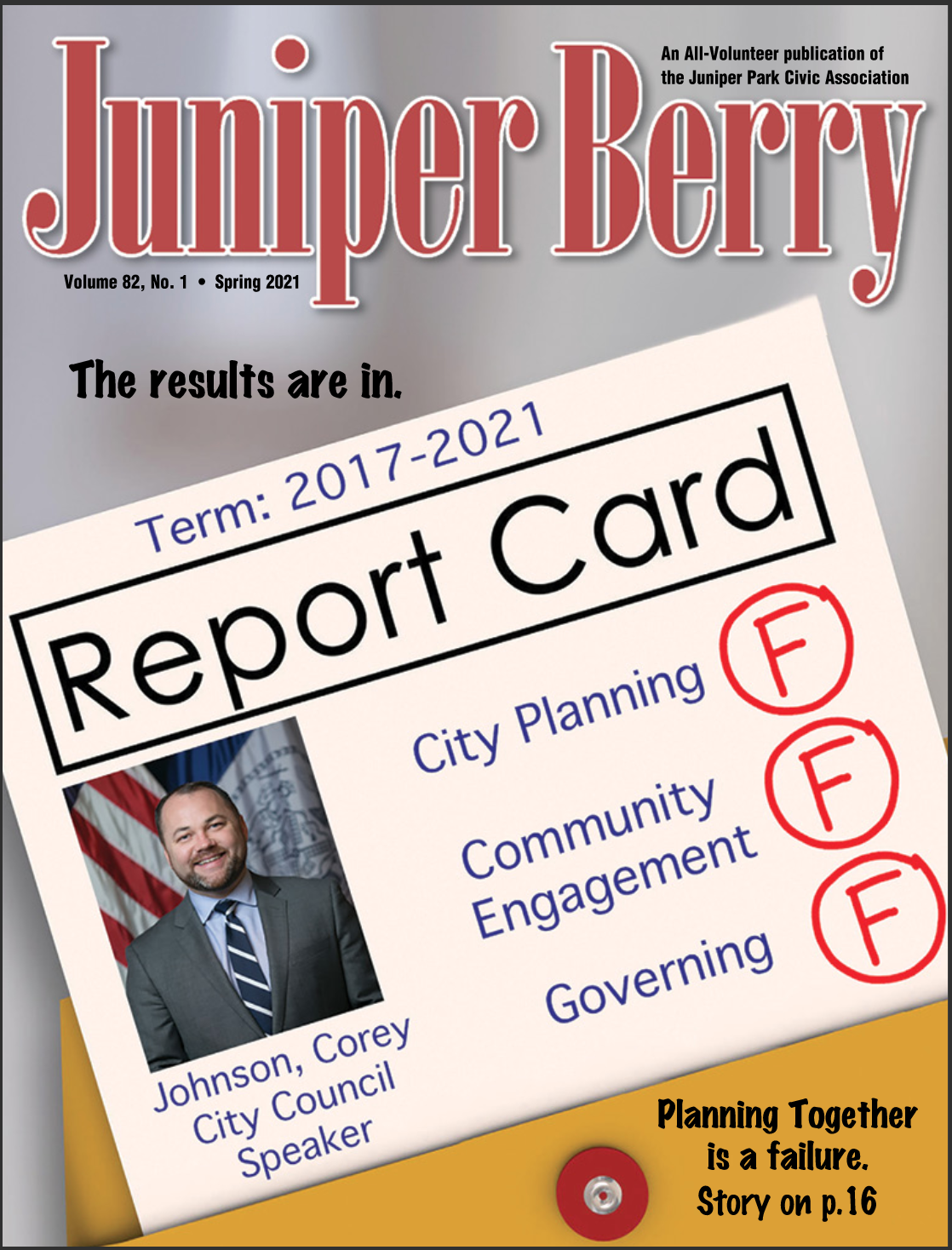

A handshake, store credit, deliveries, favors and trust, yet as always, people remained an enigma. As the neighborhood evolved, morality changed, not necessarily for the better. After relocating, one loyal customer came from way out on Long Island, calling in for a large order of imported goods unknown to the supermarkets. But most detrimental to a neighborhood remains the exodus of its sense of community, often with the departure of the families that originally built it. When citizens no longer hold the community together, either by leaving or losing the will to preserve it, security takes on new forms. Individuals must fend for themselves. Where fists and the occasional knife once defined violence, enters the gun. Shoplifting took a back seat to robbery; it was time for us to move. A .32 revolver soon laid in wait, hidden below paper bags behind the counter and frozen foods, while the hunting shotgun slept at home. And if you found yourself across the counter, you knew where the large Parmesan machete resided, hopefully appearing only to cut a few pounds of cheese, grated, at no extra charge.

Hopping onto a spring rocking horse, having your grandfather dazzle you with his pocket watch so you could be spoon fed, and turning off the black-and-white television after the Million Dollar Movie faded into distant memory. There was no sense in protecting what was no longer worth keeping. Within two weeks after my father sold the store and retired, the new Korean owner’s introduction to America was a gunpoint robbery – twice. Candles, icons and incense for sale, the grocery then became a church. Presently it is a laundromat owned by a Polish woman. But the neighborhood began to bounce back. You can buy a cell phone through the window where the candy store once kept pretzels or eat pastries at the funeral parlor, now a Spanish café bakery.

With the passing of generations and passing onto generations, few can think back without wonder at the circumstances that brought them to their present. For most, the concept of time moves forward, regardless of wealth or fame, as we imagine ourselves and our families with lives that hold something better, perhaps in a place with more to offer than we experienced. We hope for them that they have time to notice not just the gum spotted sidewalks and grungy street cleaners, or the smell of the seldom fresh washed tenements and pavements after a torrential downpour, but an open sky with shadows of clouds passing overhead, seasonal greens and white snow, sunlight on autumn leaves – yellows, oranges, browns and reds – and the laughter on children’s faces everywhere.