As an advocate for sustainable communities and sane land use policy, including increased protections for neighborhoods through zoning reform and balanced development patterns, historic preservation, land conservation, community organizing and other strategies to stabilize and increase public participation and engagement, I believe in the overall concept of comprehensive planning.

When implemented correctly – which is to say, with a balanced approach that ties all of the complex threads of planning together – municipalities of all sizes can benefit from this approach:

When the Zoning Resolution was adopted in 1961, overdevelopment potential was built into how the map was created. If every residential property were to be built out to its maximum, the city would be able to absorb between 16 and 20 million people, or more than double the 8 million at that time. 60 years later, we have approximately the same population and, even with major zoning changes over the past 20 years, the maximum development potential also remains similar as well.

In recent decades, the closest that the City of New York has ever gotten to comprehensive planning were the large-scale neighborhood rezonings that took place during the Bloomberg administration, particularly those adopted between 2005 and 2013. These rezonings were divided into two major categories: neighborhood contextual rezonings, which usually included significant downzoning components and often upzoning components as well; and massive “downtown” upzonings, such as downtown Brooklyn, Hudson Yards and Jamaica, designed to maximize development potential in urban centers rich with transit, infrastructure, business and social services.

The neighborhood contextual rezonings, particularly those where there was substantial community engagement and participation, were groundbreaking for a specific reason: under the Bloomberg administration, the Department of City Planning actually listened to the communities and stakeholders affected and worked with rather than against them in most instances. This is why these rezonings were incredibly successful, popular and achieved their purpose: comprehensively rezoning neighborhoods through large-scale actions, some encompassing 500 blocks or more at a time.

The Bloomberg rezonings were, for the most part, extremely successful because of several important components:

• Careful, fine-grained proposals that took account of the existing built environment

• New zoning designations to better reflect the diversity and gradients of housing stock

• Planning principles that focused on higher density around transit, lower density in other areas to maintain community character while promoting orderly growth

• Buy-in from the affected communities, including Community Boards and Councilmembers

• With sign-off from communities (which can sometimes take years), a speedy public approval process.

During the current de Blasio administration, the change in direction and what can only be described as an inability to respond to the needs and concerns of communities affected by their proposed and implemented rezonings has created sustained and massive backlash against them, not only from neighborhoods and Community Boards but often the elected officials representing them as well.

In the multiple crises of COVID-19, political unrest and economic instability in New York City and with term limits resulting in an almost complete turnover of elected government in this calendar year, there is a true opportunity for land use policy to take a much-needed change of direction back to working directly with the residents and stakeholders in our neighborhoods to plan for the next decade and more.

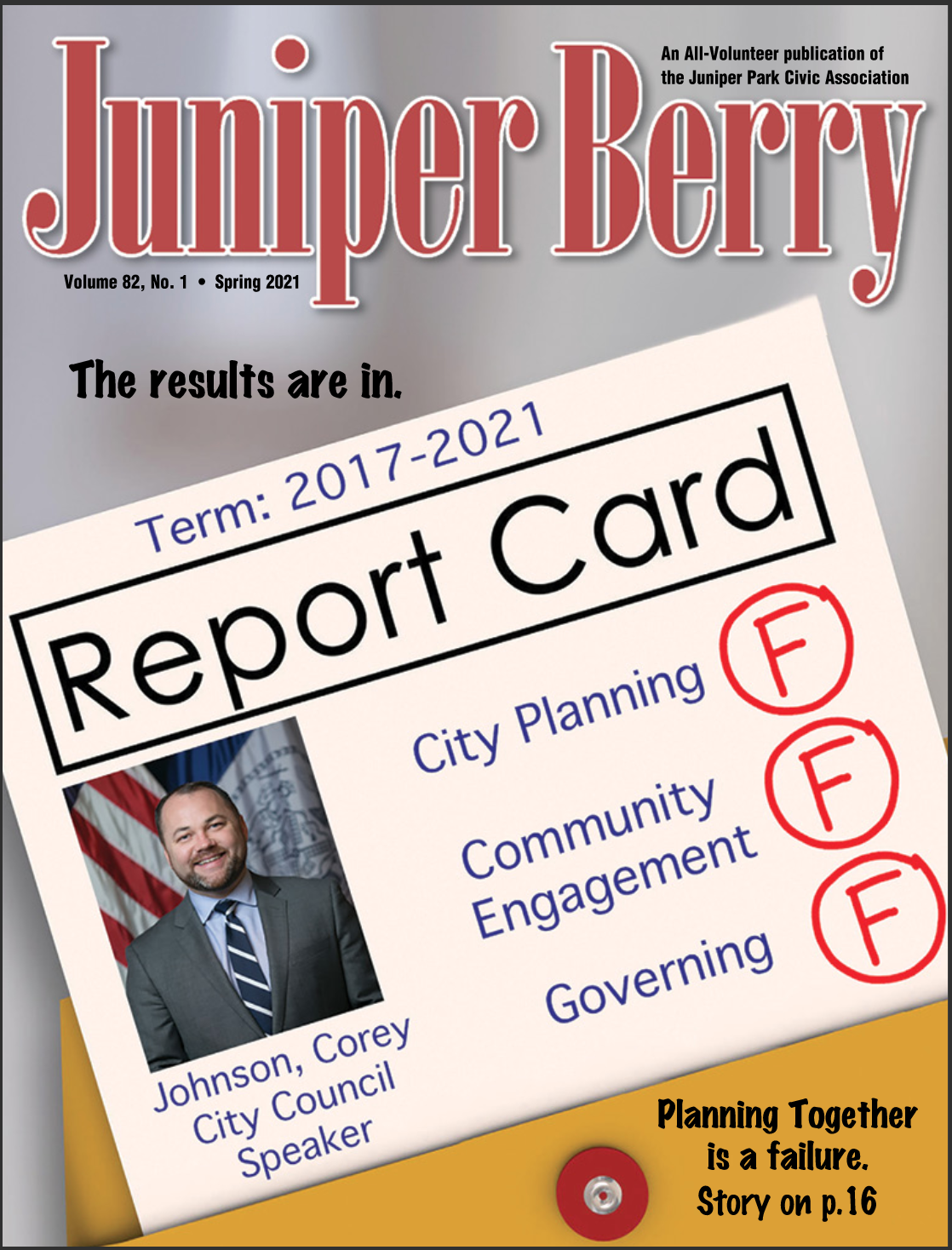

Unfortunately, the report put forth by Speaker Corey Johnson last December does not meet that standard. In fact, from the analysis that I have conducted, it does the opposite. In addition, the rollout of this report and subsequent introduction of a bill in the City Council the next day was done with virtually no outreach to the people of New York City and, most importantly, was not disseminated to Community Boards whose already-limited influence over the land use process will be greatly curtailed should this report’s goals be adopted into law.

The report is mainly built on a single fictitious pillar: that wealthy, White neighborhoods have received preferential treatment in terms of planning and zoning while, according to the report, “For Black, indigenous, and people of color, there are rarely if ever conversations about what people actually want to see in their neighborhoods.”

This falsehood is repeated multiple times throughout the document all in the name of “equality” which, in this document, relates to the removal – not enhancement – of input from neighborhoods, stakeholders, Community Boards and elected officials during the land use process; and mandatory upzonings that would have to occur in each Community Board to generate tens of thousands of new housing units in the City every decade.

This blatant lie is best expressed on page 29 in a single critical paragraph in the section entitled “Uneven Zoning Landscape that Exacerbates Socio-Economic Inequality”:

Mayor Bloomberg famously rezoned roughly 40 percent of the City’s land mass but failed to address the City’s historical neglect of people of color and lower-income neighborhoods. Instead, DCP downzoned dozens of neighborhoods in majority-white middle-income communities in Queens, Staten Island, the outer Bronx, and Brooklyn, where local civic organizations pressured the City to restrict development. The Bloomberg Administration introduced new lower density districts in those whiter, wealthier neighborhoods with strict limits on building height and bulk to “protect neighborhood character” against “overdevelopment.”

This simply is not true. A review of the 34 neighborhood-wide contextual rezonings that took place in Queens from 2005 to 2013 – more than 50% of all of the contextual rezonings which were adopted in the entirety of the City during that time – show a very different story (see maps). The areas shown are the blocks that were rezoned overlaid on demographic maps based on the raw data from the 2010 census designed by the Urban Research Maps Project (conducted by the Center for Urban Research at the CUNY Graduate Center). These maps show the four main demographics in New York City showing the majority demographic by block in a range of colors: White/Caucasian in Light to Dark Blue; African-American in Orange to Brown; Hispanic/Latinx in Light to Dark Green; and Asian- American in Pink to Purple. If no one demographic predominates or there is a plurality, the block is shown as blank.

Out of the 34 rezonings in Queens referenced below, 12 had a majority White population; 7 were majority African-American; 7 were majority Asian-American; and 4 were majority Hispanic/Latino. The remaining 4 rezonings had no one demographic predominating or had a plurality. These rezonings ranged in size from approximately 20 blocks to over 500 depending on the size of the neighborhood; they were located in all corners of the borough and completed in no particular order; and, they had overwhelming buy-in from each community, regardless of demographic background, economic status or form of stakeholder (homeowner, owner-occupied cooperative apartment or condominium, renter, business owner, etc.). Economic diversity is also shown throughout the rezonings that took place, with numerous working class, middle class and upper-middle class neighborhoods represented throughout Queens. Also, the rezonings did not focus solely on lower-density neighborhoods; many communities with middle to higher density were included as well, rounding out public policy goals of inclusiveness, not exclusivity as purported by the Speaker’s report.

As the most diverse borough in the most diverse city in the United States, over the last half-century, Queens has been a national laboratory of how different types of people can live together in dozens of neighborhoods of varied economic levels, some urban, others more suburban. Like parts of the city away from the center of gravity of Manhattan, outlying areas of Queens oftentimes have more in common with their suburban neighbors across the Nassau County line, as do areas of the north Bronx with adjacent towns in Westchester. Staten Island in particular has developed in a fashion much more similar to coastal New Jersey, where the borough has significant economic, transportation and familial ties. People from these areas of the city also have employment, commute, shop or otherwise participate in a cross-boundary economic and social framework that defies easy classification by a city government which, more often than not, focuses on a Manhattan-centric view of how the City should be.

In recent years, this has resulted in numerous attempts by the current de Blasio administration to impose new high-density zoning in low-income neighborhoods, often with tremendous opposition from the existing residents, with infrastructure improvements and dollars held hostage during the process. These rezonings, for the most part, did not increase affordability for the residents of those communities; they have, if anything, spurred on more market-rate and luxury-type development, altering the neighborhood without benefitting those who live there presently. And, as we are decades behind in needed infrastructure – for example, a medium-sized rainstorm dumps over 1 billion gallons of raw sewage into our rivers and waterways on a regular basis due to lack of capacity and control at our treatment plants – it is unfair to the communities that most need it to hold critical improvements as a carrot in exchange for significantly higher density potential, which will increase their infrastructural needs all over again.

While our current land use process is far from perfect by any standard, the proposed “streamlining” or limiting participation of our defined role in planning and land use conversations and approvals; the potential elimination of single-family zoning which creates opportunities for enormous numbers of working and middle-class residents to remain in New York City due to its relative affordability and (mostly) outlying locations away from transit; and the mandatory upzonings by Community Board area (despite or ignoring a major downturn in population in the city over the last five years, not including the past months of temporary and permanent mass-outmigration during the COVID-19 pandemic) for the sake of increasing unit counts throughout the city is not the way to facilitate “equality” for the residents and small stakeholders of our city. There is no question that New York City could benefit from real comprehensive planning – just not the anti-democratic, anti-participatory thinly-veiled development scheme as proposed in the unintentionally tragi-comically titled Planning Together.

Ironically, the Planning Together report derides the fact that the Bloomberg administration “famously rezoned roughly 40% of the City’s land mass” and continues the lie based on the Furman Center report’s falsified data that lower-income people of color were not included in the dozens of contextual rezonings that were adopted between 2003 and 2013.

During a Community Board presentation in February, the co-author of Planning Together, Annie Levers, was mystified as to how to get the rest of the city rezoned in a similar manner without passing Intro. 2186-2020. Had Mayor de Blasio and Speaker Johnson been so concerned about overdevelopment, real affordable housing and community participation (or lack thereof), there is no question that we could have had another 40% of the city carefully rezoned by now. Clearly, that hasn’t happened, and every neighborhood that hasn’t been is being preyed upon by speculative developers.

Where has the Speaker been for the past three-plus years as neighborhoods have been screaming for both the restarting of neighborhood-wide downzonings and real affordable housing? And, if he is so insistent that this bill will enhance community input rather than weaken it, why has he introduced this bill – and the first public hearing! – in the last year of a lame-duck Council with no notification whatsoever to Community Boards or the general public? And finally, if this is such a popular idea, why did essentially the same bill get rejected by the Charter Revision Commission in 2019 and never make it on to the ballot?

Folks, what we have here is not a planning problem; it’s a political problem. And, if Intro. 2186-2020 becomes the law of the land, it’s going to tear our city apart.

So, what can you, as stakeholders in your communities, do about this? The City Council is expected to vote on this legislation sometime between April and June of this year, and it is likely that term limited, legacy seeking Speaker Corey Johnson will use this as leverage in deciding which projects receive Council funding in this year’s budget. It is imperative that your council representatives vote against this and you need to make your voices heard to them. Call, write and hold them accountable. The future of your neighborhood is at stake.

IN SUMMARY:

• Speaker Corey Johnson has initiated a process to upend planning and zoning in NYC with zero outreach or notification to neighborhoods or Community Boards

• Comparisons of comprehensive planning in other cities and states are, in many cases, not applicable to our system of planning in New York City

• While real comprehensive planning for New York City is a laudable goal, the end result of this report will not do what it purportedly proposes

• The basis for this proposal is built on a series of statements presented as facts which are not true and are, in fact, the opposite of the experiences of Community Boards and communities throughout New York City

• The proposal will remove, not enhance, input from

neighborhoods, Community Boards and elected officials

• Mandatory upzonings would be required every decade in each Community Board area regardless of the fact that the population of New York City has remained relatively stable (give or take 1 million) for over 60 years and our current zoning has the capacity to absorb more than double our current population

• The proposal neglects to take into consideration one of the hallmarks of New York City development: as-of-right

• Contrary to the report, elimination of single-family zoning will have a deleterious effect on the entire city, with no increase in affordability, only stresses on infrastructure away from transit

For more analysis, visit this link.